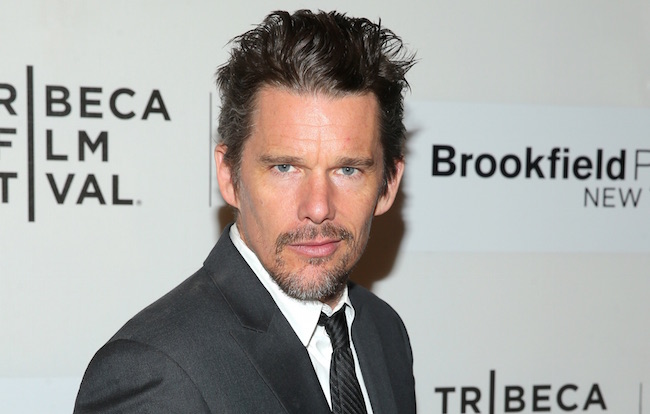

“Some people have a midlife crisis and they buy a Porsche,” jokes Ethan Hawke. “I had a midlife crisis and made a documentary about a piano player.” Last September, Ethan Hawke — just a few months before being nominated for an Academy Award for his work in Boyhood — premiered his documentary, Seymour: An Introduction to a film festival crowd. Hawke used that documentary as a sort of self-deconstruction, openly pining about his own career, even though the film was technically about a pianist named Seymour Bernstein. It made an interesting contrast, if, for nothing else, to see an Academy Award nominated actor have a “What am I doing with my life?” moment just like the rest of us.

The thing is, this moment of self-reflection sure hasn’t stopped Hawke’s output. He has nine (!!!) films slated for release in 2015, one of those being Good Kill, which premiered last September at the Venice Film Festival and is currently showing at the Tribeca Film Festival.

In the film, Hawke plays Major Thomas Egan in what would be a sad and realistic 2015 sequel to Top Gun. A trained fighter pilot, Egan finds himself stationed at a Las Vegas Air Force base in which he’s piloting armed drones a half a world away instead of being an actual pilot. Not to mention that he’s dealing with the internal struggle of controlling a device that can kill with just the press of a button.

On Monday morning, I was supposed to meet Hawke in person, but a bug that’s going around New York City forced me into changing those plans. So, instead, I spoke to (a gratefully still not infected) Hawke on the phone about his self-described “midlife crisis” and why it’s impossible to make a living as an actor in independent films.

How are you doing?

Good, man. How are you?

Doing well. That’s a lie. I caught a bug that’s been going around, I don’t know why I just lied to you to start this off.

It’s okay. Don’t worry.

I didn’t want to show up and possibly infect people.

Well, I appreciate that. I’d much rather talk this way than get the bubonic plague.

See, I didn’t need to lie.

There you go.

This is probably a weird comparison, but Good Kill feels like the sad, realistic sequel to Top Gun.

You know, it makes me so happy that you say that. That was my whole theory about Major Thomas Egan, that he watched Top Gun when it came out and that was his dream. And for a hot minute, he got to do it – you know, learn to fly some fighter jets. He got to feel like he was part of the solution and, like the rest of the Air Force, he’s falling into a philosophical identity crisis. Where does it leave the whole Air Force when these unmanned aircraft are so effective? And more effective than a manned aircraft could ever be.

Right…

It’s actually an extension of what’s happening to the whole culture. All of our lives get more and more remote and we all end up more and more disconnected. War is obviously a heightened experience that most of us don’t participate in, but you see it dramatized really clearly in how the military is changing.

Even watching the fictionalized images of the drone strikes in this film, it’s apparent how somebody could get desensitized to this, as opposed to if a pilot is actually there in the heat of the moment.

Yeah. Exactly. Flying an F-16 is really difficult. It takes years to learn how to do it. Flying a drone is not and it is desensitizing. And if you’re actually performing a mission where you’re living in the area and getting to know the people, it’s a whole different experience. Your adrenaline is flying and you’re putting your life at risk to the courage of your convictions, whereas these guys are being asked to make mortal decisions in a very anonymous way.

It is disconcerting.

What’s strange about it, the movie is a period piece. It feels so much like science fiction. For me, it feels so dystopian, you can’t imagine Philip K. Dick coming up with the idea of remote controlled aircrafts that you’re going to control from Las Vegas, city of sin… what’s interesting about the drones is that it’s clearly an extremely effective tool in the U.S. arsenal and there are so many positives. When you think about the bombing of Dresden, people talk about the collateral damage with drones, but it’s a huge leap forward in the ability to limit collateral damage. But it’s also a little bit like shooting off the heads of dandelions across your front yard. You can get them all, but are you really stopping the weed problem? Or are you making it look good for a hot second until everything grows back more?

It’s almost like having the power to smite someone.

I know. And it’s so unpoliced. It really is like the fist of God just comes down, boom, and you’re it.

Your documentary, Seymour: An Introduction, felt like a deconstruction of yourself. You express a lot of concerns about your career, but I look at your filmography and you’re not slowing down.

[Laughs] Well, that’s an interesting question. My joke answer is that some people have a midlife crisis and they buy a Porsche, I had a midlife crisis and made a documentary about a piano player. I certainly haven’t slowed down. Part of it is me and I think as you understand mortality and understand how limited our time is here, I feel kind of more motivated. And another part of it is simply the time period we live in. Independent film, it’s harder and harder to make a living doing it. It’s strange, when I first started making movies, your average film would shoot around 12 to 14 weeks. Then it kind of went down to 10. Now, most movies shoot in like six weeks. They all used to pay a little bit, now everybody wants to give you backend, and nobody wants to pay you. So, for me to make a living, I kind of have to work more.

We always hear actors say, “One for them, one for me.” Last time we spoke, I could tell you wanted to talk about anything other than that movie you were promoting.

[Laughs] For sure.

Boyhood hadn’t come out yet and it was obvious you would much rather talk about that. But your above explanation makes sense.

Look, as much as people like Boyhood and Before Midnight or my documentary, as much as critics like those movies, they don’t begin to cover the tuition of one child’s school, or my child support, or anything. So, it’s a dance. And it’s the dance that most adults have to go through: How do you stay in touch with your dreams? How do you remain idealistic? And, at the same time find compromises that you can live with yourself about. You know, the thing that Cassavetti said, it’s fine to work for money as long as you know what you really want to be working for. If you work for money too long, you can lose your dream and you don’t know what you’re saving your money for. And I’ve always tried to stay in touch with what I really love to do.

I think most people would agree with that about you.

And you’ve got to find ways to be a professional. To kind of take pride in being a craftsman and doing a good job. And, to be honest, I have to be grateful to how little I’ve had to do that. We love to talk about how great Daniel Day-Lewis is or something, my joke is that it’s pretty easy to be great with Tony Kushner writing and Steven Spielberg directing. What’s really hard is being good on an episode of Matlock. Now that’s f*cking challenging.

I’m glad we’re reevaluating Andy Griffith’s late Matlock career.

Exactly!

And then a few months after premiering your documentary that includes a reassessment of your career, you get nominated for an Oscar.

You know, this has been a great time period for me. Boyhood is an experience that made me believe in movies again. That was the biggest pipe dream of my life. I’ve never done anything more risky and weird and eccentric than that. And to have that go well, it really makes you believe it’s worthwhile to gamble and try and to chase the dream.

Mike Ryan has written for The Huffington Post, Wired, Vanity Fair and New York. He is senior entertainment writer at Uproxx. You can contact him directly on Twitter.