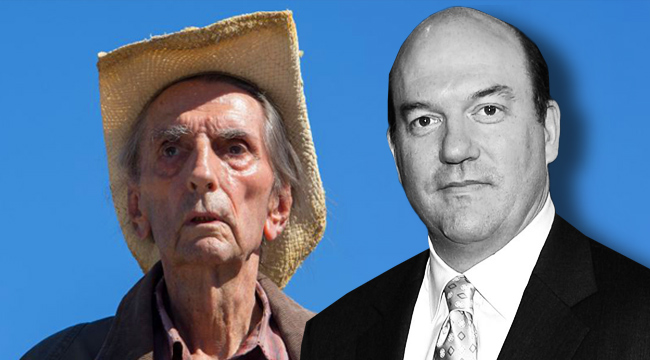

Chances are you’ve seen John Carroll Lynch, a veteran character actor for almost 25 years. He’s appeared in everything from Fargo to The Founder to The Drew Carey Show to The Walking Dead. Recently, Lynch made the decision to step behind the camera to direct Lucky, a semi-fictionalized account of the life of 90-year-old Hollywood legend Harry Dean Stanton. The film made its world-premiere this year during SXSW, and we got the chance to sit down with the first-time director about bringing the mythos of Stanton to the big screen.

What was it that drew you to Lucky for your directorial debut?

I was asked by the writers of the movie [Logan Sparks and Drago Samonja]. They were starting to put it together. I had known Drago for a long time, Logan I had known for a few years too, and they brought me the script as an actor. They wanted me to attach myself to act in the movie, and I liked the script and I was like, “Yeah, cool. No problem. If it helps you at all, attach my name.”

For years, [Drago had] known I had a desire to direct, and that I’d followed people and trailed people, and it just hadn’t quite come together. A couple of months later, they asked me if I wanted to direct the piece. I was like, “Well, yeah. I do.” I told them the story of the movie, what I thought it was. We worked on it for a while together, walking through it to move things around a little bit and to talk about what each scene was. Then we started going out to cast and financiers, and ended up making the movie pretty quickly, because everybody knew there was a time crunch.

What was your shooting schedule?

18 days, with a 19th satellite day in Arizona. And we had staggered weeks. So we started with a two day week, and then started on Thursday [and] Friday, and then gave Harry two days off. Then three days, and then we gave Harry two days off. We did it that way because I had just finished a shoot as an 18-day shoot as an actor, that I was in every day, and I knew how exhausting it was. And I’m a little over half Harry’s age.

So we knew we had to husband his energy, wanted to make sure he could go home every night. We wanted to get him out and so there was that kind of economy was necessary, both budgetarily and also structure-wise, because we wanted to make sure that Harry could do what he needed to do.

And he’s in just about every frame of the movie.

Soup to nuts, man. He’s in every scene. Every scene starts and ends with Lucky.

Was he the actor you had in mind from the get-go?

Well, he wasn’t the actor I had in mind from the get-go. It was tailor-made for him. Logan has known Harry for 15 years and when Logan wasn’t acting or producing something on his own, or writing or whatever, he’ll go on the road as Harry’s assistant, but really they’re just friends. He goes over there every day, whether he’s working for Harry at that time or not.

And Drago has known Harry as well, because Drago did a beautiful documentary called Character, and that’s how I knew Drago, along with a short film that we did together. Big admirer of Drago’s work, both as an actor and as a filmmaker, so when he handed me the script, I took it seriously.

So it was written with him in mind?

It was written for him. Kind of about him, really. I guess I would say it this way: Logan and Drago took the stories and legends that Harry has told to them over the course of knowing him, and took the essential essence of, I think, what Harry believes about the world, and created a fictional circumstance and a story that told that. It’s a very personal movie for Harry Dean.

With your experience as a character actor, how did you approach this as a director. Especially a movie like that that’s almost entirely character actors.

When we talked about it, there were essentially four or five films that were in the writers’ minds in terms of style and vista, you know. All ’70s movies, basically. Last Picture Show, Midnight Express, and Paris, Texas obviously is a great influence on this movie, as it is in Harry’s life. Also, I said it feels sometimes like we’re making a movie that asks the questions, “What if John Ford made a character piece?” You want a sense of space and vista. [Cinematographer] Tim Suhrstedt did a beautiful job, and he too came to play with Harry Dean. That’s the reason why I did the movie.

Everybody came to do that. It’s a celebration of him. But as an actor, you know, I approach material as an actor first and foremost because that’s my training and that’s my experience and where I feel most at home. Other aspects of filmmaking are new to me, and I embraced some well, and others were less comfortable, but all of it was a really large learning curve.

18 days is a pretty tight turnaround time for any project.

For any project. I mean, I saw a movie that was shot in 11 days here, and I was talking to the woman who directed it, she said, “How many days did you have for Lucky?” I said, “18.” She said, “I’m arguing about 32! Like how can I do this movie in 32 days?”

There are a number of little touches in it, like David Lynch’s character, Howard, always wearing an untied bowtie.

Actors bring things to the piece. Lisa Norcia, the costume designer, did a lovely job with her work as a storyteller. [But] the bowtie, that was David.

It seems like something he’d come up with.

I wanted Howard in a bowtie. And he came in with it untied, and as often happens with actors, myself included. When I want a bowtie, they can be difficult to tie oneself. I can do it now, [so] I thought maybe perhaps that was what was going on. I said, “David, do you need some…?” [He responded.] “No, no.” I went, “Okay. Good. Looks good.”

He’d be a guy whose instincts you could trust.

Yes. As a director, unless there’s a reason I need something a particular way because it’s going to affect another character or the rhythm of the scene or some subsequent piece of business or some subsequent scene, David or not David… I mean, it’s David Lynch, so he knows what he’s doing.

I mean, you’re a host. First and foremost, directors are hosts. You want everybody to have a good time at the party. I’ve never found it effective to stick to something for no reason. You got to have a reason to do it. And that looked great to me, and I thought it was interesting. I was like, “I’m not sure why he wants to do it, but that’s not my business. I’m okay with it.”

Were there ever disagreements about how to approach something?

If I had a problem, I would. Like first scene we did with David was with Ron and David and when Harry is picking that fight. And David sat down, I asked him the bow tie question, and then he was wearing his hat. I said, “So what do you think about taking the hat off?” He said, “Well, if I take this hat off, they’ll know it’s me.” I was like, “Well this is the second scene, so if you take your hat off here, that’d be great. We can have your hat on at the bar.” And he said, “Okay.”

For me, I mean, I haven’t talked to David about it, obviously, but for me, I sensed that he felt vulnerable. He knows his iconographic status, he’s aware of it, he’s not wrong about it. His hair is a primary aspect of that. So he wanted to make sure that people took him as the character of Howard, and not as himself.

I was confident in the way he was playing it that no one would think twice about it, because I know how presentation works as an actor. And we, as an audience, want to believe that someone is somebody else. So when they say they are, we’ll give them the benefit of the doubt. It’s only when they prove us wrong by doing something that feels false that I will stop giving them that license. So he wore the hat at the bar, which I think he was right about: it did help kind of break up the iconography. I don’t think you think twice about the fact that when he says he’s Howard, he’s Howard. I have no problems believing he’s Howard.

And like you’d pointed out, he’s such a prominent figure in pop culture.

He’s a zeitgiest dude, man.

You mentioned Jim Jarmusch as an influence, and an easy comparison would be his latest, Paterson. But it was also reminiscent of Coffee and Cigarettes. Lucky’s the thread, but all these little conversational vignettes hover around a much more profound idea.

Well, the feeling of mortality, I don’t know how you feel about it, but I always feel like my own mortality is something that I need to really concentrate on. It’s like a muscle in your back that’s sore and you know it’s there and you try to push your thumb on it and it just slips away, and you can never get that knot out, but you know it’s there, so you just kind of live with it. This movie, because Lucky is 89, 90 years old, and doesn’t have faith to fall back on. He doesn’t have a god that says it’s going to be okay for him. He has to squarely look at mortality dead in the eye, because the road looks a lot shorter.

We’re under the illusion that the road isn’t as short for everybody, but it is. And that’s what I think I love about this movie, because it’s not maudlin about it and it’s not nostalgic about it, and it’s not sentimental about it, but it’s not cold, either.

I don’t want to get too specific here, but there are a couple of substantial moments that are really hidden beneath the layers.

What’s the best way to express the way in which things seem to work for me? It’s kind of like the David and the tie thing. Actually, there’s a better example from Zodiac. So in the last scene of Zodiac, where I’m in the hardware store and Jake [Gyllenhaal] opens the door, you know, Graysmith opens the door and walks through, he’s looking for me. So he comes in and it’s like, to me, the scene is basically Ahab and the whale, so he’s Ahab and I’m the whale, and he’s going to find out if he’s really the guy, just man to man. I’m at the counter, he comes in, we have that scene.

So I’m watching the scene, and I burst out laughing, because I am behind an Ace Hardware sign that says, “Your Featured Item.” I laughed [and] said to [David] Fincher, “That’s brilliant!” He goes, “What’s that?” I said, “Well, the sign. I’m behind the sign, ‘Your Featured Item.'” He says, “Oh, yeah. Yeah, that’s right.” I don’t know if he was just fucking with me, which I doubt, because he has no reason to, or he just was like, “Oh wow, the art director was really on it that day.”

[For Lucky], you collaborate with people, right, and they’re going to bring what they bring. We’re all working on an unconscious level too.