Like all bits of art and protest that outspoken UK rocker, author, and activist Billy Bragg commits himself too, the book Roots, Radicals, And Rockers: How Skiffle Changed The World comes from the heart, and comes with a purpose. Bragg’s cause this time is the enlightenment of passionate music fans who have been fed a narrative about rock and roll and the British Invasion that is light on a transformative phase. Skiffle — a high energy bit of sound that emanated from the UK’s lower class following World War II by way of New Orleans, American jazz, blues, and folk music — had a hand in the establishment of Lennon and McCartney’s friendship and in stoking their interest in music. Same as it did with Van Morrison, Neil Diamond, and so many others who took the energy of skiffle and branched out with their own sounds.

In an interview with Bragg, we spoke about the importance of skiffle, its heritage and ownership, the challenges of reaching people through music in these divisive times, discovering the real America on the railway, and why Bragg, who abhors cynicism, believes this political moment is one that is ripe to inspire change.

The book is really great. It’s just super dense. I’m a musical history nerd and I really didn’t know much about Skiffle going in.

That’s great to hear because I kind of wrote it with people like you in mind, people who have a deep appreciation of the roots of music but don’t really have any cognition of skiffle on account of its sort of obscure treatment by the rock journalists in the late twentieth century.

I remember going through a music history class and they just glossed right over it. It went Elvis to the British Invasion. They act as though there’s nothing in the middle there.

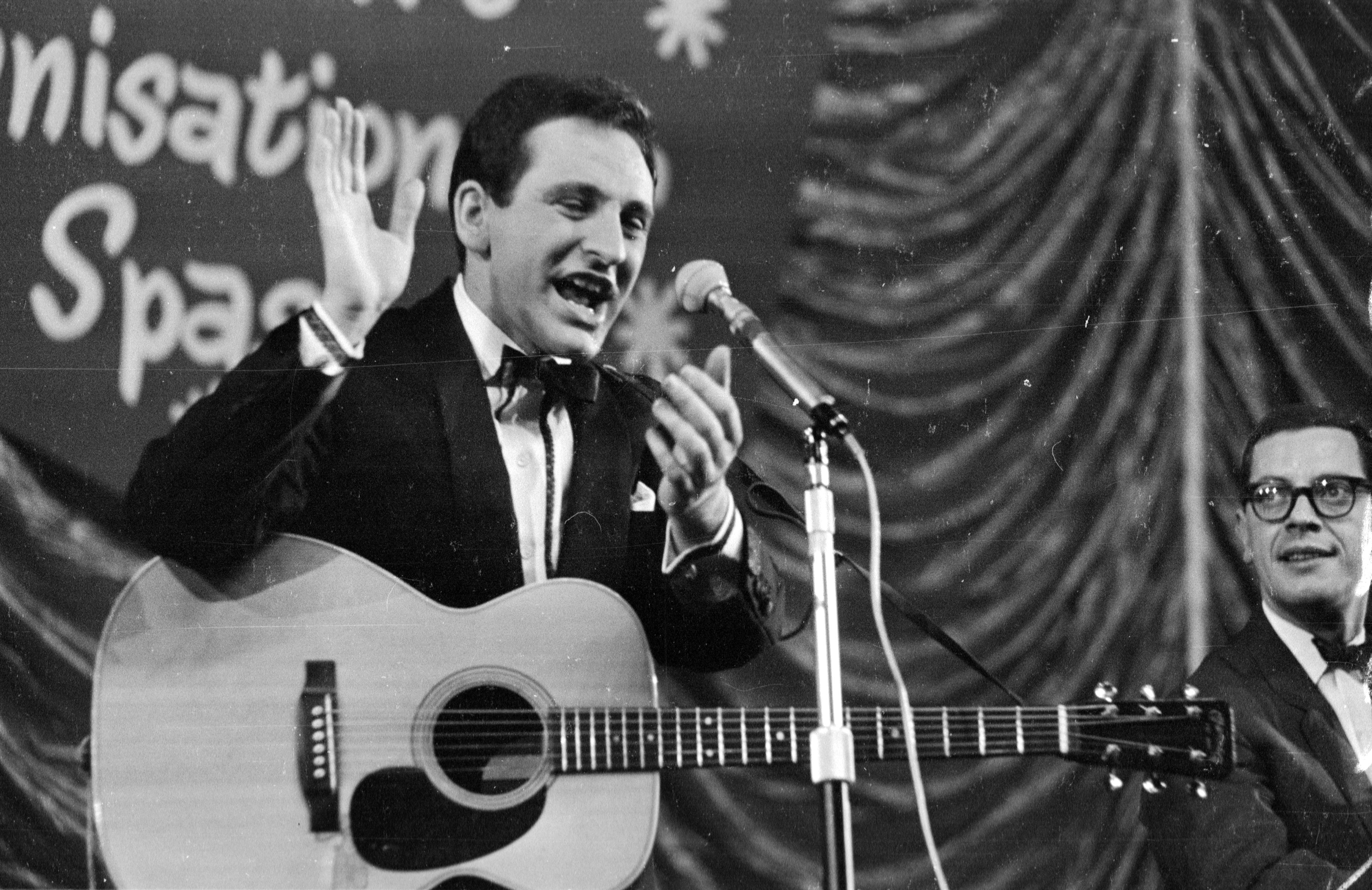

Yeah. In my country, it’s… ‘oh yeah, Lonnie Donegan had a hit with ‘Rock Island Line.’ It all started there.’ It’s like the Big Bang, you know? It wasn’t a singularity. There was a number of very important… This is the first defining music of our first [post World War II] generation of teenagers. You’d think it would have a little bit more respect.

Let’s get into that. I guess that’s the driving force behind this, right? Shining a light on a type of music that hasn’t gotten a lot of attention.

Yeah, just to try and contextualize it in British pop history. Popular culture, that’s what it’s at. It is also an attempt to explain it to Americans, as well. I was very conscious of that. That it was accessible to an American audience so there are plenty of points of reference for them along the way. It’s impossible to write a book about skiffle without writing about America anyway. But I wanted to make sure that it wasn’t just something that would only make sense to Brits.

I really appreciate that you went deep into what preceded skiffle, as well. Of course, the blues is at the center of so many musical movements. You touch on it in the book a little bit with the whole Fred Hellerman thing, but what would you say to someone who dismisses skiffle and its historic value as just another instance of white people stealing black music?

Well, you know, Lonnie Donegan in 1956 had a hit with a song called “Stewball.” Which is a song about a racehorse that talks to its owner and tells it how to win a race. And he got that from a Lead Belly record, and a Woody Guthrie recording as well.

Now, they probably got it from a recording made by Lomax Senior, I think. John Lomax, in the ’30s when he wrote his book about American vernacular music. John Lomax said that “Stewball” was the culmination of work songs that came across being sung by African-American field workers in the 1930s. Now, a hundred years before that it was being sung in the bars in New York. And fifty years before that, the song was being sold on the streets of London. But the actual event itself that the song is based on actually happened in Ireland. So who does that song belong to, do you think?

It’s definitely hard to assign any kind of ownership in that instance.

It’s impossible, yeah. Particularly when you’re talking about songs from the pre-record industry era before copyright comes in and ownership becomes the main transactional aspect of popular culture. These things go around, come around.

You know, Woody Guthrie wrote once about some songs he learned from his grandmother. I mean, these were songs… and “Stewball” was one of them interestingly. “Gypsy Davy” — that song was being sung in Britain during the time of Shakespeare.

You know the way culture comes across, particularly across the Atlantic, I think it’s a very, very interesting phenomenon. And it’s very hard to say who starts what where. I think we find that… I mean most people think Lead Belly wrote “Rock Island Line.” He didn’t. He adapted it the same way that Donegan adapted it.

In some ways, Donegan watermarked it by introducing the toll booth into the narrative because Lead Belly doesn’t mention a toll booth. So, if anybody who sings “Rock Island Line” mentions a toll booth, they’re copying Lonnie Donegan’s work. This includes Johnny Cash on the first track on his first album for Sun Records. He’s not ripping off Lead Belly, Donegan is his connection to Lead Belly.

You can have the whole of music history in your pocket, so it’s a little harder to say that certain types of music aren’t given a chance to shine or that people can’t have any knowledge of certain types of music. Is it different now when record companies are involved and other types of cultural appropriation happen?

I think it is now. I think now that you can see that there’s a clear identification of where a song comes from and who originally wrote that song and what they were talking about. But I think back then, those divisions were invisible to someone like Lonnie Donegan.

He just loved the music. He loved the authenticity of it. And he just wanted to try and connect with what Lead Belly was talking about. To him, it was a way of transcending post-war Britain. Of transcending the bomb sites. Of transcending the rationing. And making the connection with African-American culture, which he wasn’t able to do on anything in his own culture because it was all mediated by the BBC. And those voices were kept out.

What was your initial connection to skiffle?

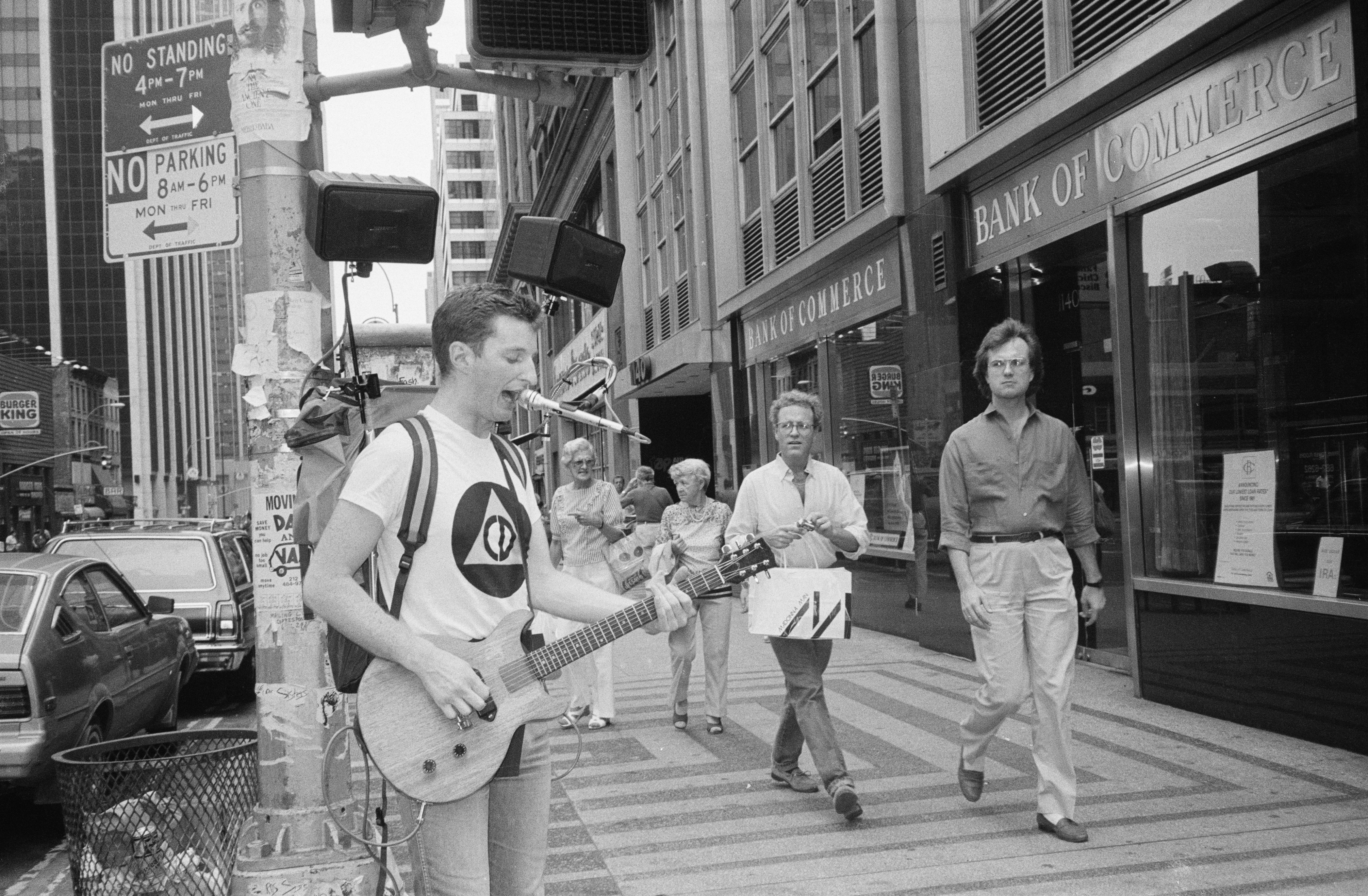

By the time I got listening to music it had been forgotten. Other layers of pop had been laid down and it wasn’t really visible. I bought one of the first TV compilation albums. It was a compilation of ’50s American rock and roll, but it had a Lonnie Donegan track on it called “Cumberland Gap,” which is a two chord thrash through an old American folk song. It’s a bit high speed. And I could hear from that that this wasn’t rock and roll. It’s an acoustic guitar. It’s not an electric guitar. There was definitely something weird about this. Because I, you know, I thought I knew what rock and roll was because I’d heard Elvis. I must have been about 12 or so at the time, maybe 11. And I later come to find that it was skiffle.

The more I learned about skiffle, the more I began to think of it as being very similar to punk rock. And I wanted to kind of explore that kind of possibility, so I thought I’d buy books about it. But the books written about it, where the subject matter was skiffle, tended to be written by guys who were there at the time. So they kind of spoke from inside the actual events. There was very little that put skiffle into its context and that’s what I was looking for. Part of the problem is that you can’t talk about it without talking about Trad Jazz. And Trad Jazz has not been hip for 60 years, really. It was the music of our parents. It was… you know, you couldn’t really go there. Nobody was interested in that.

For me, it was finding out about Ken Colyer and his obsession with New Orleans jazz and his great pilgrimage to New Orleans. I kind of came to see what he was trying to do, which was to try and respond to the commerciality of mainstream jazz at the time, which was swing. He was responding to that and rejecting that. It was inauthentic. And trying to get back to basics.

And I saw in there a similar response in both The Ramones in your country and Dr. Feelgood in my country, who were responding to the commerciality of, and the vapidity of, guitar rock in the mid-’70s. By going back to basics and trying to renew the rock and roll by playing hard and fast and raw and [with] no solos. And that’s kind of what skiffle was and also what trad jazz is. The thing about New Orleans jazz is there are no soloists. It’s a collective effort.

The process [of researching this] is what, I guess, inspired you to do the “Shine A Light” album with Joe Henry, right?

It was. I had come to realize that there were so many American railroad songs in so many different genres in the US as a kind of a folk memory of a time when the railroad was absolutely revolutionary culture. It changed everything in the United States of America.

Before it came, you could only move if you were in a city on a river. And if you lived on a river and lived in the interior, rather, the chances are that river didn’t go to New York or Chicago or Los Angeles. It went to only one place and that was New Orleans. It went to the Caribbean. That Caribbean culture reached right up into the center of the United States of America through the Mississippi, Missouri, the Ohio… They all kind of go to New Orleans. And that’s why I needed to tell that story as well, because I needed to get British music fans to understand why New Orleans was so important to British music. Most people think of more New York or Chicago or Memphis.

I think there’s an argument to be made that it’s New Orleans that was actually the key city in the development of British rock.

And you toured the railroads in the process of making that album, right?

Yeah, we just got on the trains in Chicago and rode the rails as far as San Antonio, all the way to Los Angeles. I’ve been traveling your country for over 30 years by airplane and by a sort of van, driving to cities and I… On the train I saw an America I’d never seen before.

You know, you look into peoples’ backyards. You’re looking into trailer parks. You’re looking down river beds. The train follows the route… most of it laid down over a hundred years ago, some of it dated over 150 years ago — the route between San Antonio and Los Angeles. So it’s the second transcontinental crossing. And so you’ve gone to places that used to be important. It’s kind of like the railroad is the fossilized remains of the Industrial Revolution America.

This was a time when, you know, the election was just gearing up, the fireworks were gearing up, so Trump was talking about building this wall. And there we are in El Paso, Texas, where you can stand right on the platform of the railway station and throw a baseball into Mexico. It’s that close. And you can see over there. You can see the poverty.

Juarez is just outside the border. On the outskirts of Juarez, it looked like the set of The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly. Me and Joe couldn’t believe it. And then you look the opposite way, literally out the other window of the train, and you’re looking into the suburbs of El Paso and it’s all, you know, big trucks, and you know, SUVs, and swimming pools. And you look back across the border and it’s just incredible — the difference. It’s very revealing where the railroad goes.

You’re kind of going at a much slower pace than the rest of America. Don’t bet on getting in on time anywhere, because a friend of mine did the same route and warned me. The same route and they were twenty-four hours late getting in, but that’s just it. Once you’re on the train, you kind of have to give up and get into that time. Everybody on the train with you knows there in a different time, they’re sort of time travelers. They’re doing something that very few people in America do anymore.

It sounds like an enriching experience for the perspective. It kind of feels like something we should all do.

That was the interesting thing that the four Americans I was traveling with — Joe, the engineer, and the two guys that were filming. They were as blown away with it as I was. You know, from starting off, the engineer complaining about how slow it was. By the time he got to LA, he was talking about the next time he goes to visit his father in Denver, taking the train.

It was great. I mean it really was an amazing trip. It showed me an America that I’ve never seen, that I didn’t even think was still there.

You mentioned the American election before, and you’re known as a very political person, a protest rocker. Can you talk about the challenge of reaching a new, or unconvinced audience, when it comes to protest songs now when there’s so much noise and it seems like people are sort of dug in?

I think what’s happened is that music has lost its vanguard role in youth culture. In the twentith century, it was the only social medium we had. We didn’t think of it like that, but it was kind of all we had. And music had to talk about everything that we were interested in. And we fleshed out those ideas in the music press. You know, there were four music papers in the UK, and that’s the heavyweight ones, and then there were even more pulp ones knocking around. So, you know, music had to be the form in which we identified ourselves to each other and to our parent’s generation. Music doesn’t play that role anymore.

There are far few people willing to take that. I think of Beyonce at the Super Bowl being one example. The grime artists who stood with Jeremy Corbyn during our election. There weren’t no white boys with guitars… Ed Sheeran didn’t pop up and say he believed that Jeremy Corbyn is a good example. It’s those people that are still trying to get their message in the mainstream from outside that are still using music. But for the most of us, we’re embedded in the mainstream now because of the digitalization of culture, I think.

I mean, music still has a role to play, don’t get me wrong, because you can get something you can’t get online. And that’s essential communion with other people. Whether it’s over love songs, political songs, or whatever. You know, when you’re singing together that song that you really love, whatever emotions you attach to it are completely accepted by everybody. So, you know, that ain’t gonna change, I don’t think. But to imagine that music will be the main way that people get their politics, which is how I got my politics in the twentieth century, I think that’s more difficult to do now.

Is it fear of losing out on other opportunities because you’re too outspoken? Bigger artists, pop artists that are a little hesitant to get political because of any kind of perceived blow-back. Do you think that’s the case?

Well, I think for a while politics wasn’t very fashionable. The kind of centrist politics didn’t really align themselves to musical causes, really. The generation gap seems to have disappeared now. My son listens to the same music I listen to most of the time. So that aspect of music doesn’t really work anymore, but interestingly, Brexit seems to have woken young people up in my country. They seem to have suddenly realized that politics actually does mean something. And I think in your country, it’s the same with Trump.

You’ll find that the next election more and more young people are engaged because they suddenly realize whether or not they’re interested in politics, politics is interested in them.

I think it’s that. I think it’s also Black Lives Matter and seeing racial inequality here — something has turned on. I think the hip-hop community seems to have, like, gotten more political over the last five years or so.

I mean, I think the key thing about those that you mention is that they’re people of color and they’re trying to get their message into the mainstream, into mainstream America. And they know that they can still do that with music. But I think for, you know, white youth it’s a different situation. They themselves need to feel that they’re under pressure. I don’t think that the last 20 years has really done that heavily. But it is now. I think with the arrival of Trump and the arrival of Brexit. Now, they do realize that they need to turn up. They need to be woke. They need to understand. And support the group of Black Lives Matter. And they’ve been engaged in general causes.

Like me, when I was 19 years old, they probably didn’t think that mainstream politics meant anything to them. I mean, I didn’t vote when I had the first chance to vote in 1979. I didn’t vote and Margaret Thatcher got elected. And I grew up to be Billy Bragg, so, you know, it’s difficult for me to say to young people who didn’t vote in your election last year and our election that you’re failures because it took the election of Margaret Thatcher to wake me up.

I think Brexit in my country and Trump in your country will have that effect. And that’s what we showed in our general election, I mean, the momentum the anti-Brexit brigade have now… more young people voted than previously, and they may have derailed the whole process. At the very least they’ve created a space for us to have a discussion about whether or not it’s a good idea and that’s quite significant. Never let anyone tell you voting don’t change nothing.

Roots, Radicals, And Rockers: How Skiffle Changed The World is available now, as is Bragg’s latest protest song, The Sleep Of Reason, which was inspired by Goya’s The Sleep Of Reason Produces Monsters and 2016’s political upheaval.