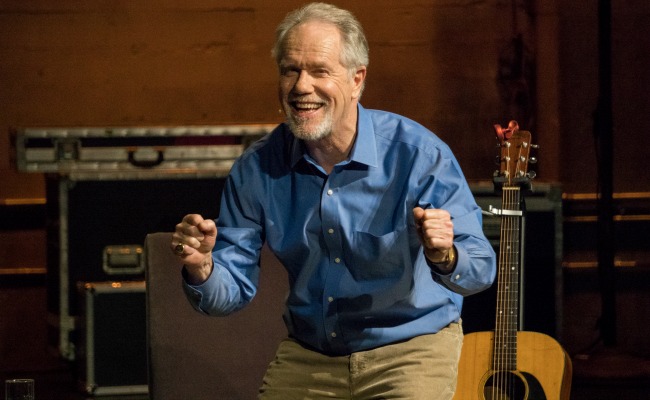

I may have been the wrong person to interview Loudon Wainwright III and write an article about his new music and storytelling filled Netflix special, Surviving Twin (which you can stream now). It’s not that I’m unfamiliar with the veteran folk singer’s work — I’m familiar. (“One Man Guy,” his hard pose about living a solitary life, is a sometimes anthem for me.) It’s not even that I didn’t find the show interesting. Loudon III captivates as he connects the man he’s become to the man his long-dead father was by mixing a selection of his own songs with excerpts from Loudon Wainwright Jr.’s Life Magazine columns. The thing is, a piece about complex father and son relationships kicks up a lot of dust for me: I haven’t spoken with my own father in more than three years.

I’m more bothered by unearned father and son reunions in TV shows and movies than I should be. But I’ve thought long and hard about it and, despite the universality of some of the messaging, I don’t think Surviving Twin is trying to ram home the idea that stubborn young people need to quickly and fully forgive the stubborn old people in their lives as some kind of one-size-fits-all solution. Wainwright III didn’t get to the place where he could make this special overnight, and when I talked with him — and shared a very small piece of my own experience — he seems the kind to respect the journey that every broken kid needs to take. But as a father in his early seventies, and with the perspective that comes with that (on matters past, present, and pending), he doubtlessly sees value for his life in moving beyond grudges and accepting that he and his father are inextricably linked.

“They’ve all grown up,” Wainwright III says to me when discussing Rufus, Martha, Lucy, and Alexandra — his kids, with whom he has had a sometimes complex relationship. “I’m always trying to figure out a way that we can start over,” he adds. One of those ways is to follow some of his father Loudon Jr.’s words, recounted for me and in the special: “Not what we were, or think we were, but what we have become.” It is, as Loudon III says, “a beautiful idea” for reframing how we look at our parents and how they look at us — eschewing nostalgia and bitterness for a focus on the present. But, Loudon III also acknowledges that it’s not easy to pull off.

Catharsis

When I ask Wainwright III if the special has helped him with his own issues with his father, he points to his long history of writing about his family. The subject is perpetually “interesting” to him, but “it doesn’t really solve anything. It’s not therapeutic.” There is, however, a sense of “catharsis” and a deep want for the audience to find the same. “In a sense that’s more important than anything else,” he said.

While Surviving Twin should be classified as a deeply personal work, it tries hard to provide that desired release for the viewer, doing what good art is supposed to do by inspiring introspection. Whether you want it to or not.

Here’s the tale of the tape: Wainwright III and I have both had complicated relationships with our fathers, but he’s had more time to allow for any wounds to scab, and then scar. And that time matters. Perspective matters too. At this point, I’ve lived half as long as Wainwright III and, right now, I love my grudge. It fuels me and reinforces the idea of who I am — someone who is strong enough to make a hard decision and live with it. Though what “strong” is for you and me may vary — and everything I just wrote might prove itself to be bullsh*t as I get older.

“Both,” Wainwright III says when I ask if it was the accumulation of time after his father’s death or advanced maturity that led him to accept his enduring presence in his life. “Everybody’s different.”

Memories

There’s a point in Surviving Twin where Loudon III reads from a story by Loudon Jr. about his father’s father, Loudon Sr., who died young and never really told his son how he felt about him. “Even if we’re late, we can still reach out for fathers and find good moments for ourselves in what they left behind,” Loudon III says to me, recounting Loudon Jr.’s emotionally heavy words as he wrote about finding an old movie of himself ice skating as a child that his father had recorded. “I think, that, almost more than any sentence that he wrote in this show, is what this show is about.”

Wainwright III is right, but as with so much of the experience of watching Surviving Twin and talking with him, I find myself wrapped up in the emotion of the message and unbending in my desire to resist it.

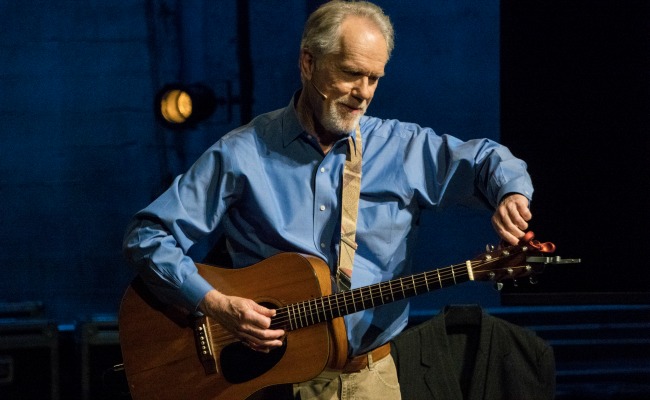

The song “Four Mirrors” plays a prominent part in Surviving Twin. Originally released in 1997, Wainwright III’s fresh performance of it fills the show’s trailer (above) and serves as the penultimate song in the special. Its accuracy is undeniable. Seeing your father in your reflection or hearing yourself speak in the way that he did (or does) can bring you closer to that person, but it can also be a burden when you want to forget. The same effect is present when thinking back on those good moments that Loudon Jr. referenced; the baseball games, the nights ragging on whatever was on TV, those times he calmed a storm just by listening.

Wainwright III agrees when I suggest that people sometimes need to metaphorically split their fathers into two people — the one tied to all those happier memories and the one whose memory complicates them. “Our parents are gigantic. You love them and you hate them and you hate them. You want them and you don’t want them. It’s a big thing. They are two people.” That method is how I hang on to those good moments without succumbing to sadness. Even if, sometimes, it feels like it’s barely working.

Resolutions

The music for this special is well selected and poignant, especially “Four Mirrors” and the title track, but Wainwright III’s affection for his father’s words tells the deeper story. It’s not just that they’re starkly brilliant and timeless (though, these specific stories were selected for exactly that reason from a pile of about 200 that contained more era-specific musings). It’s that they’re a piece of a puzzle that the son has built to more fully get to know his father. Something every son probably wishes they could do. Including me.

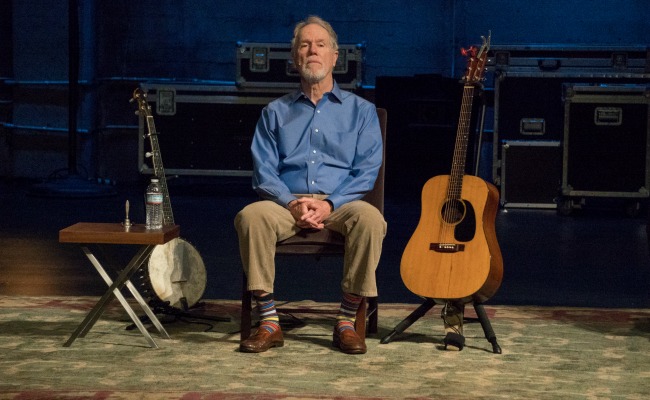

“He was a mysterious, talented, complicated, depressed (it has to be said) guy. Funny, also. People loved him, including me. We did not have a close relationship which is a great pity,” Wainwright III said, before telling me that finding his father’s work allowed him the chance to more fully appreciate him. “I’m a fan. I wasn’t a fan before because I was hung up about, ‘he’s my dad and he’s more important than I am.’ We were locked in a kind of an Oedipal struggle. Now I’m 72-years-old. He’s been dead for more than 25 years and we’re getting along great. I love that we can have this kind of posthumous collaboration.”

I am raw from the elongated experience of Surviving Twin, which, for me, includes watching the special, going back to certain parts repeatedly, speaking with Loudon Wainwright III, and beating these words into place. The whole thing took longer than most things like this do — at least twenty late night and early morning hours across a few days — to say nothing of the time it’s spent at the forefront of my mind, as I reflected on these themes and my own story. The resolution to all of this is… nothing. Everything just rolls along as it was. Make no mistake, I’m floored by Surviving Twin and as happy as a stranger can be for Loudon Wainwright III. I’m also jealous of him for how he can look in the mirror, wrestle with the realization that he’s his father’s surviving twin, and be alright with that. Even be comforted by it.

Hard hearts need a prompt to soften, and this sure did loosen some things up for me, but enough? If stories about the complexities between fathers and sons resonate with you and you need only a gentle push toward reconciliation, this might do the trick and I think that’s great. But I’m stuck in the mud and alright enough with it to keep it that way. Every day brings a new look in the mirror and a fresh thought about who I am and who I want to be, though. No matter who’s looking back at me.

Surviving Twin is available to stream on Netflix now.