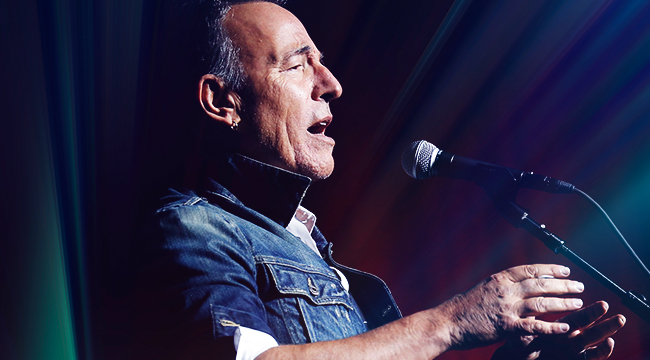

Moments before I pressed play on my Netflix screener of Springsteen On Broadway, Thom Zimny’s concert film premiering Sunday, I felt some unexpected trepidation. I had been lucky enough to score an absurdly good ticket to the Boss’ hugely successful one-man show — fourth row center! — the month it opened in October 2017, and was blown away. “Is it a concert? A play? Performance art? Whatever you call it, Springsteen On Broadway is one of the best shows I’ve ever seen,” I gasped in my lengthy review, like the Bruce fanboy I undeniably am.

How could a filmed version possibly compare? In person, Springsteen On Broadway (which finally wraps its historic run at the Walter Kerr Theatre at the end of this week) was overwhelming for its uncommon intimacy. In the Springsteen-iverse, the illusion of closeness is afforded strictly by proxy on folkie, pared-back detours like Nebraska and The Ghost Of Tom Joad. Prior to Springsteen On Broadway, I had never viewed him from any nearer than 100 feet. From that vantage, even a rock god appears to be only six inches tall. On Broadway, thrillingly, he was suddenly life-size and right there.

During the two-and-a-half hour show, which intersperses music with homilies drawn from Springsteen’s life, I found myself continually choking up at the mere sound of Springsteen’s relatively hushed, conversational voice. I was used to hearing my hero scream over the E Street Band and 50,000 Brooooooooce-ing fanatics. But the miracle of seeing Springsteen On Broadway in the flesh is that it made Springsteen suddenly much more dynamic, like a high-dimension image that’s exponentially higher than 1080p.

A particularly emotional moment came during an extended monologue about his hometown of Freehold, in which he reminisced about the things about your home that you only romanticize when you know they’re gone forever — the clanging sounds from the regional rug mill, the omnipresent smell of the local Nescafé plant, the dead-end bars that function as receptacles for broken people with dashed dreams. And then, inevitably, he played a song I’ve heard approximately 5,321 times, “My Hometown” from Born In The USA. Only now it was as if I was hearing it for the first time — Bruce sat at a piano and softly sang the words, gently tamping down his iconic sandpaper huskiness, like it was a bedtime lullaby. As if Bruce was your dad, imparting wisdom.

In moments like these, Springsteen engaged his audience in ways that are impossible in an arena, even for the most accomplished arena-rocker of all-time. How in the hell can a Bruce Springsteen fan be expected to hold it together through that?

On Netflix, Springsteen is downgraded back to 1080p. And, like listening to a bootleg of your favorite concert, there are times when Springsteen On Broadway suffers a little in translation. For one, the experience itself obviously is less focused. When 1.5 billion hours of Office reruns are just one click away, it’s hard to imagine many viewers having the patience to watch a 69-year-old man talk for 153 minutes.

Other shortcomings are hardwired into the piece itself. In person, one of my favorite sections of Springsteen On Broadway occurred when Springsteen’s wife and bandmate, Patti Scialfa, guested on two songs from Tunnel Of Love, “Tougher Than The Rest” and “Brilliant Disguise.” But revisiting these performances in the Netflix special made me wish that Springsteen would’ve ceded more to Patti. In the show, Zimny inserts shots of Patti stoically looking on while Bruce talks (and talks) philosophically about marriage. He is, as always, eloquent and insightful, though noticeably little less candid than he is about his parents or his own naked ambition, artistic and otherwise.

I kept wondering: What does she think when Bruce sings, “Now you play the loving woman / I’ll play the faithful man / but just don’t look too close / into the palm of my hand”? How illuminating would Mrs. Springsteen On Broadway be?

Overall, Springsteen On Broadway is still pretty amazing. And, yes, it still chokes me up, because that special intimacy inherent to the stage production has been similarly made a focal point of the film. In fact, that closeness has been enhanced to an even higher level of intensity.

Unlike most concert films, the audience is mostly excluded from Springsteen On Broadway. Zimny keeps his cameras trained almost always on Bruce, only occasionally cutting to wider shots that frame him amid silhouetted theater-goers. Zimny, crucially, posits Springsteen less as a rock performer than as an actor giving a performance, an aesthetic choice that nods to the show’s central thematic concern: Springsteen’s meta-exploration of the space between himself, an aspirational though often troubled introvert, and the all-American archetype he created as his life’s work.

Even during the so-called “poptimism” era, when critics have a knee-jerk distrust of hoary concepts like “authenticity” and “honesty,” there’s still a general conflation of musicians with the protagonists of their songs. This is doubly true for somebody like Springsteen, whose cult of personality rapidly subsumed his art back when he first broke through to a mass audience nearly 45 years ago with Born To Run. So, it’s been fascinating to watch Springsteen kick back against this with increasing rigor in his later years. In Springsteen On Broadway, he points out the obvious — he never worked in a factory, or even a 9-to-5 job — while inviting you to see him as a hybrid of Martin Scorsese, Robert De Niro, and Paul Schrader. The director, writer, and actor of his own myth.

In case there is any doubt, Springsteen truly is a wonderful actor, equally adept at comedy and pathos. Freed from the necessities of reaching the cheap seats at Giants Stadium, he finally has the benefit in Springsteen On Broadway of deploying a more subtle set of movements and facial expressions. He sells his stories and songs with the tilt of his head, the shrug of his shoulders, a long exhale, or a pregnant pause. He reminds me a little of Al Pacino — both the understated ’70s Pacino and the hoo-ah ’90s Pacino. He can be bombastic. He pontificates. He spits hot air. But his “overheated baptist preacher” routine ultimately sets up an affecting contrast with Springsteen’s rapt stage whisper, which comes out whenever he talks about his family or his own mortality.

Before “Long Time Coming,” an allegory from 2004’s Devils And Dust in which a man wishes for his children to be freed from the mistakes of their predecessors, Springsteen shares an incredible story about his father visiting right before the birth of his first child, and apologizing for their dysfunctional relationship. When he relates it in Springsteen On Broadway, the close-up is tight enough to subtly spotlight his gently reddened eyes.

When I saw Springsteen On Broadway, I was lulled into believing that Bruce was somehow spontaneously conjuring the entire show in the moment. This, as Springsteen sardonically intones at the show’s start, is essential to his “magic trick” as a musician. But Springsteen On Broadway, the Netflix special, illuminates the performative aspects of Springsteen’s art and persona in a way that manages to detract from neither. I don’t know if he cried every night before “Long Time Coming,” but making you believe he did is the crux of Springsteen’s job.

For some, this might cheapen his music, though it shouldn’t. After all, the song isn’t called feel it all night, it’s prove it all night. And the power of Springsteen On Broadway has once again be manifested.

Springsteen On Broadway will be available for Netflix streaming subscribers on December 15.