Bruce Springsteen has described his new Broadway show as a “third entity,” a hybrid of songs and storytelling that’s neither a straightforward musical performance nor a conventional one-man show. Currently slated for a sold-out run through February at Manhattan’s Walter Kerr Theatre after officially opening last Thursday, Springsteen On Broadway is essentially an adaptation of Springsteen’s 2016 memoir, Born To Run, borrowing the book’s structure and much of the “dialogue,” which unfurls on a teleprompter posted near the balcony that Bruce only fitfully feels compelled to consult.

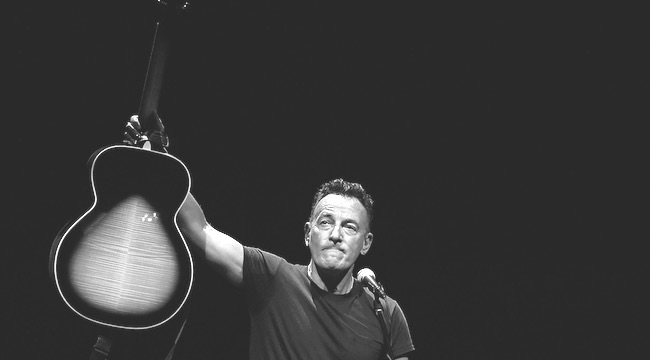

The show works like this: Bruce stands on stage for two hours, mostly alone — save for a stunning two-song cameo by his wife, Patti Scialfa — and performs 15 tracks from throughout his 45-year recording career on guitar and piano. And he also talks about the things that inform those songs: His father, his mother, rock and roll, Jersey, The Big Man, fame, social justice, transcendence, America. Is it a concert? A play? Performance art? Whatever you call it, Springsteen On Broadway is one of the best shows I’ve ever seen.

For the Springsteen fanatic — here’s where I admit that I’m afflicted with that incurable disease — the central appeal of Springsteen On Broadway is intimacy. That is the invaluable commodity that people are paying thousands of dollars for, the sort of uncommonly close proximity to Springsteen that can’t be felt even from a killer spot in front of the stage on an E Street Band tour. The 960-seat Walter Kerr Theatre is between 1/20th and 1/50th the size of the arenas and stadiums that Bruce normally plays. When I saw Springsteen On Broadway last Friday, I was seated dead center in the fourth row, approximately a dozen feet from the Boss. I was so close that I could keep tabs on a fly that circled Bruce throughout the show’s second half. If I had a fly swatter, I could’ve leaned forward and smashed it. Maybe he would’ve appreciated that.

When you see Springsteen in a venue that small, what’s most overpowering is his voice — how strange and incredible it is to hear that iconic carburetor roar without amplification and pitched down to a level several notches below “arena-rock scream.” When Bruce sat behind the piano to play a starkly mournful “My Hometown,” or was bathed in vivid red light and boundless shadows while rendering “The Promised Land” into a hardscrabble desert ballad, I felt my throat close and sinuses flair, a near-Pavlovian response to a uniquely direct and personal experience. I’ve loved Springsteen songs for as long as I’ve loved songs, but this was something else — this felt like a late-night conversation, or a warm embrace. To label Springsteen On Broadway a tearjerker doesn’t go far enough. Bruce might as well have literally reached out and pulled the tears out of my eyes.

But is Springsteen On Broadway truly an unprecedented “third entity”? In form, perhaps, but the substance is familiar. “I think an audience always wants two things. They want to feel at home and they want to be surprised,” Springsteen recently told The New York Times. For Springsteen On Broadway, the staging (highlighted by the inventive but unobtrusive work of Tony-winning lighting director Natasha Katz) is a revelation, but the narrative picks up a thread that’s been a constant in Springsteen’s career. This narrative is, in fact, the very essence of his art.

At the start of the show, Springsteen revives the knowing preface from Born To Run, “I am here to provide proof of life to that ever elusive, never completely believable ‘us,'” he says. “That is my magic trick.” As a preamble to Springsteen On Broadway, this functions as a both a tell and a nut graph, summing up what is about to unfold while also acknowledging what’s really going on. A few moments later, Springsteen refers to himself as a “fraud,” joking that rock’s preeminent chronicler of road trips and the inner workings of ’69s Chevys didn’t know how to drive until his twenties.

The self-deprecation is disarming, but ultimately an act of misdirection. Springsteen On Broadway isn’t really about deconstructing the mythology of the Boss. It’s an affirmation of that mythology, a testament to its lasting power and resonance. Like the book, Springsteen On Broadway is really a story about a story, written by a lonely misfit kid from Freehold, New Jersey who went on to invent a larger-than-life, world-conquering superhero named Bruce Springsteen.

In 2005, Springsteen’s commercial and artistic breakthrough, Born To Run, was reissued in observance of the album’s 30th anniversary. The record was accompanied by a new 90-minute making-of documentary, Wings For Wheels, narrated by Springsteen himself. The voiceover is pure Bruce — analytical and evocative, he’s a natural at describing the drudgery of songwriting and record-making while also elevating that hard work to the heights of a romantic quest. “I liked the phrase,” he says of the iconic album title, “because it suggested a cinematic drama that I thought would work with the music I was writing.” Even back then, Bruce thought of his music in terms of a grand narrative.

As I watched Springsteen On Broadway, I thought about Wings For Wheels, as well as the fascinating documentaries released in conjunction of subsequent reissues of Darkness On The Edge Of Town and The River. Springsteen has been telling these stories about himself for years, well before Springsteen On Broadway.

While mythology has played an essential role in fortifying the enduring legends of classic rock — whether it’s Bob Dylan’s culture-shaking work of the ’60s, David Bowie’s paradigm-shifting provocations of the ’70s, or the flaming-torches-at-Red Rocks triumphalism of U2 in the ’80s — nobody has been more hands-on about shaping the story arc of his own career than Springsteen. It’s hard to imagine peers like Dylan, Neil Young, Lou Reed, or Tom Petty breaking down their songs with the insight and acuity of a rock critic. But Springsteen has done this — in magazine profiles, documentaries, and now Broadway — from virtually the beginning of his career. He even hired an actual rock critic, Jon Landau — the man who had famously called him “rock and roll’s future” shortly before going on Springsteen’s payroll — to be his manager.

More important is how Springsteen’s has woven a personal narrative through his songs, starting with “Growin’ Up” from his 1973 debut, Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. The opening verse is a variation on the “magic trick” riff from Springsteen’s memoir and Springsteen On Broadway, only from the perspective of a kid who hasn’t actually pulled it off yet. In “Growin’ Up,” dreams of stardom and artistic greatness are still only fantasies.

I stood stone-like at midnight, suspended in my masquerade

I combed my hair till it was just right and commanded the night brigade

I was open to pain and crossed by the rain and I walked on a crooked crutch

I strolled all alone through a fallout zone and come out with my soul untouched

I hid in the clouded wrath of the crowd, but when they said, “Sit down, ” I stood up

Ooh…growin’ up

By Born To Run, Springsteen was writing the myth of the E Street Band in “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out,” inserting a special shoutout to his on-stage sidekick, Clarence “Big Man” Clemons, back when Springsteen didn’t have a pot to piss in. On his next record, Darkness On The Edge Of Town, Springsteen started writing about his father, likening his boyhood struggle with Douglas Springsteen to a biblical fable in “Adam Raised A Cain,” and using the elder Springsteen’s dead-end life as a journeyman laborer as an allegory for American blue-collar malaise in “Factory.”

As Springsteen’s career grew, and he went from being a cult-y attraction in northeast clubs to one of the top touring attractions in the US by the end of the ’70s, he also refined his penchant for on-stage storytelling as a connective thread between his myth-making songs. Anyone who’s pored over Springsteen bootlegs knows about the tales of hurt and defiance that prefaced songs like “Independence Day” and his gut-wrenching cover of the Animals’ “It’s My Life,” in which Bruce would talk for minutes on end about his troubled childhood and how rock and roll saved him from the misery that befell his father. While Springsteen’s colloquial delivery suggested that these stories were spontaneous and extemporaneous, he would actually spend hours backstage crafting them for maximum emotional impact, like a comedian carefully placing the exact right number of beats in a joke.

The ability to buy into Springsteen as an idea is what separates fans from critics. Springsteen agnostics have long seized upon the supposed hypocrisy of the Springsteen narrative, an argument once summed up by the man himself as the “rich man in a poor man’s shirt” fallacy. Near the end of his 1997 book The Mansion On The Hill, a classic takedown of ’60s and ’70s rock stars who embraced the corporate music industry in the ’80s and ’90s, journalist Fred Goodman takes Springsteen to task for proffering an everyman image in his music while buying a $14 million Beverly Hills mansion in the wake of Born In The U.S.A.‘s massive commercial success in the mid-’80s.

“Whatever Springsteen said onstage about community and the need to fight the good fight in your hometown, he celebrated a distinctively different vision of the American Dream in his private life,” Goodman writes. “And now made his home in David Geffen’s community.”

As someone who started listening to Springsteen in kindergarten at the height of Born In The U.S.A.-mania, this criticism has always seemed misguided, akin to finding fault with Robert De Niro because he’s not actually an insane cab driver, or Denzel Washington for not really being the living embodiment of Malcom X. It misjudges what people who love Springsteen get out of his story — acknowledgment of their own problems, hope that they might escape these pitfalls, and joy at the excuse to dance over all those worries. Whereas Dylan escaped into a persona as a shield from the public, Springsteen has used his persona as a soapbox, transforming himself into something bigger and more heroic for an audience that views his personal experiences (or the versions of those personal experiences that Springsteen writes about in his songs) as universal metaphors. Springsteen might be a “fraud,” as he puts it in Springsteen On Broadway, but that doesn’t make his story any less true, not when so many people see themselves in that story, creating that ever elusive, never completely believable “us” united in devotion to Bruce.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BaJ-XfKFlR6/?hl=en&taken-by=springsteen

I’m reluctant to discuss Springsteen On Broadway in too much detail for fear that it might spoil the experience for those who will be seeing it in the months ahead, or drive those who failed to get tickets mad with envy. However, there are a few moments I’d like to single out, because they illustrate how this show elaborates upon the story that Springsteen has been sharing in his music since the early ’70s.

My favorite part of the show unquestionably were two songs from 1987’s Tunnel Of Love that Springsteen performed as a duet with his wife, Patti Scialfa. Tunnel Of Love is known as the “divorce album” in Springsteen lore, documenting the dissolution of his first marriage to the actress Julianne Phillips. Scialfa, a member of the E Street Band who rapidly became Springsteen’s girlfriend around the time that he broke up with Phillips, is all over Tunnel Of Love, her ghostly backing vocals adding a layer of real-life psychodrama to songs like “One Step Up,” in which a married man trapped in a doomed marriage contemplates sleeping with another woman.

In Springsteen On Broadway, Springsteen and Scialfa first join together for “Tougher Than The Rest,” Tunnel Of Love‘s stouthearted pledge of steadfast devotion. Unlike the bulk of the album, “Tougher Than The Rest” presents the sort of relationship that anyone would want. “The road is dark / and it’s a thin, thin line / but I want you to know I’ll walk it for you anytime,” Springsteen sings on the record, without Scialfa, which informs the meaning of those lines, making them seem like an act of seduction performed on a potential, unseen lover. But when sung with Scialfa in Springsteen On Broadway, “Tougher Than The Rest” blossoms into a sacred vow to never leave your soulmate behind.

After this ray of light came darkness in the form of “Brilliant Disguise,” one of Springsteen’s greatest tunes and one of the most candid rock songs ever written about marriage. In Springsteen On Broadway, “Brilliant Disguise” is nothing less than a tightrope — performing a song about duplicity, and the impossibility of knowing what lies in the depths of another person’s heart, with the woman you go to bed with every night ups the ante on a song already freighted with sky-high emotional stakes.

“Brilliant Disguise” is also an Easter egg in Springsteen On Broadway. In the song’s final verse, the protagonist goes from obsessing about his wife’s infidelity to confessing that he is also not what he seems. At this part of the song, Springsteen and Scialfa subtly shift their bodies, from facing each other to facing the audience. “Is that me baby?” they sing to the audience, “Or just a brilliant disguise?” Were they talking about the elusive meaning of love, or the slippery nature of Springsteen’s own artistry?

In that moment, I didn’t feel like I knew anything special about Bruce and Patti’s marriage, even though I was sitting close enough to notice Patti silently mouth “I love you baby” to Bruce as she walked offstage. (This was definitely one of those times when dust magically appeared in my eyes.) What I gained instead was insight into what it means to make a life with someone for almost 30 years, and the devotion and compromises that requires.

The final quarter of Springsteen On Broadway resembles a typical Springsteen show, veering from the introspection of the first 90 minutes to the deliver the rousing, life-affirming energy that some many of us have come to rely upon from our hero. Near the show’s close, before playing “Born To Run,” Springsteen refers again to “my magic trick,” which he now also calls a “long and noisy prayer.” He sends the audience away with the hope that this prayer will be “read, heard, sung, and altered by you and your blood, that it might strengthen and help make sense of your story.” This narrative, he insists, wasn’t really about him at all. It’s about finding the inspiration to be better in our own lives. We all wish we could be Bruce Springsteen, even Bruce Springsteen.