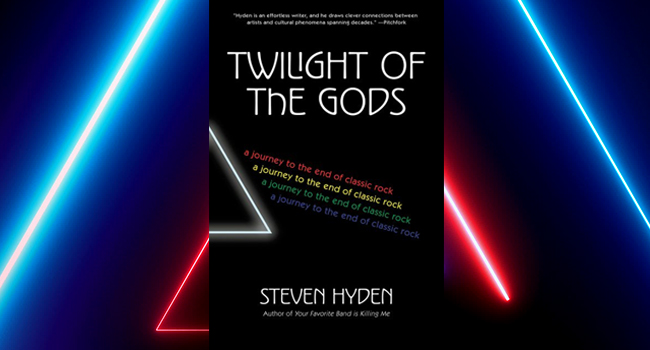

On May 8, Uproxx Cultural Critic Steven Hyden will release his new book, Twilight Of The Gods: A Journey To The End Of Classic Rock, from Dey Street Books, which you can order now. In this exclusive excerpt, he writes about how the term “dad rock” came to be applied to so many bands.

My new book, Twilight Of The Gods: A Journey To The End Of Classic Rock, covers topics such as Frampton Comes Alive! and Bob Seger’s “Turn the Page” and David Bowie’s cocaine habits in the ’70s. If that sounds interesting to you, I’m going to assume that you’ve heard the term “dad rock.” I’m also going to assume that you like dad rock. This is good, because I (obviously) also like dad rock. A lot.

But let’s say you have no clue what dad rock is. In the parlance of our times, “dad rock” is used to describe three kinds of bands.

1. A dad-rock band is a band that your dad liked when he was young.

The most straightforward definition. Initially, dad rock was meant to describe popular if also unfashionable groups from the ’60s and ’70s — Steely Dan is probably the most emblematic dad-rock band of all time, though dadness is also strong with the Eagles, Jimmy Buffett, Paul Simon, and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. However, dads have gotten younger over time, so now it also applies to bands from the ’90s, like Pearl Jam and Wilco. (The current generation of dads might very well be the last for whom rock is popular enough for “dad rock” to work as a recognizable signifier.)

2. A dad-rock band is a band that is consciously and unapologetically influenced by bands from the ’60s and ’70s.

This version of dad rock was born in the ’80s with groups like U2 and R.E.M., who came up during the first decade in which rock music was divided into distinct halves by the advent of punk and the rise of classic-rock radio. These twin events severed modern rock from its past, even as rock’s past survived and weirdly carried on a parallel life in competition with modern rock. To some, the act of plugging in a guitar was now automatically construed as “retro” or “nostalgic” (i.e., the judgmental form of “retro”). It was now possible to sound like a rock band and act like a rock band and perform rock-band-like tasks in a contemporary setting and be viewed as not contemporary.

This gap between rock’s “classic” and post-“classic” periods created a battle of conflicting impulses—burying the past vs. building upon the roots — that every subsequent important rock band has had to reconcile. For dad rockers, many of whom came to the music as it started its cultural decline, rock ’n’ roll was like folk music, a tradition handed down as a box of tools that could be used to build and fortify a subculture outside of the pop mainstream. Chris Robinson of the Black Crowes — one of the defining dad-rock bands of the ’90s — once referred to this continuum in a Behind The Music episode as “the song,” an ongoing collabo- ration between an unborn future and the mythical past to create something that feels a little realer and more permanent than the latest trends.

3. A dad-rock band is a band composed of dudes who are old enough to be dads.

This one is tricky, because a band can start out in stark opposition to dad rock in one decade and then age into dad rock in another decade. Sonic Youth was not a dad-rock band in the ’80s but became a dad-rock band in the ’00s. Yo La Tengo also became a dad-rock band at that time. So did Pavement. Sleater-Kinney became a dad-rock band in spite of being made up of women. This is all just a function of the space-time continuum.

No matter which of the three definitions apply, classifying a band or artist as dad rock is generally understood to be a putdown. For starters, the word “dad” has a terrible connotation in rock history. Jim Morrison wanted to kill his dad. Harry Chapin suggested that karma eventually screws your dad over, because (of course) he’s a jerk. Paul Westerberg and Kurt Cobain both distinguished dads (bad) from fathers (less bad) in “Androgynous” and “Serve The Servants,” respectively, agreeing on the overall failure of their respective patriarchs as male role models.

In terms of dad rock, the modifier “dad” is meant to weaken the word “rock,” divorcing it from any sense of power, danger, or sexual excitement. This matters if you care about classic rock, because the implicitly negative epithet “dad rock” has overshadowed the implicitly positive “classic rock” as the favored term for how rock ’n’ roll is now discussed.

It’s hard to pin down who exactly coined “dad rock.” It seems to have derived, as so many memorable insults have, from the British music press of the 1990s. According to legend, a nameless English scribe came up with the term as a snarky dismissal of a photo featuring Oasis’s Noel Gallagher, the Jam’s Paul Weller, and Paul McCartney hanging out at a recording session in 1995 for a charity album benefiting Bosnian refugees. (This sounds like a setup to a joke but I swear it’s not.)

While searching for dad rock’s rhetorical roots, I reached out to Simon Reynolds, the best and probably most famous British rock critic of the last 25 years. (He’s certainly the best and most famous British rock critic for whom I had an email address.) I fired off a terse, half-baked, five-sentence email asking if he remembered hearing fellow writers use “dad rock” back in the ’90s. Forty minutes later, Reynolds replied with a pithy 400-word response that could’ve appeared with minimal editing in a special dad-rock issue of Uncut. This man produced insightful music commentary with the improvisational flair that Duane Allman once applied to 10-minute guitar solos.

“It was an insult term by people who didn’t like this sort of traditional, backward-looking band and were vaguely disturbed by the erasure of the generation gap,” Reynolds told me. The biggest British band of the era, Oasis, epitomized the “sort of traditional, backward-looking band” that dad-rock critics despised, Reynolds wrote.

Dad-rock bands view rock history as a tapestry that connects present-day bands to the icons of the past—it’s an argument in favor of young people empathizing with their parents, which is always going to be a hard sell for some people. For Gen X critics systematically dismantling the boomer-rock canon and replacing it with post-punk and hip-hop records, it was pretty much impossible.

Now, we wouldn’t be talking about dad rock today if the term had only been used to admonish young Tony Blair voters for liking the Verve instead of Roni fucking Size. It only matters because “dad rock” eventually migrated to America and became a commonly used cliché for stateside music writers, due in large part to one review of Wilco’s languorous sixth album, 2007’s Sky Blue Sky, by the popular indie-music site Pitchfork.

When Pitchfork was founded in 1996, its mission was to cover all the bands that never got mentioned in Rolling Stone. The site represented a stand by Gen Xers against the boomers, but also a strike against mainstream rock by the underground, foreshadowing the impending end of the classic-rock era. In the Pitchfork universe, Neutral Milk Hotel and the Smiths mattered more than the Foo Fighters and U2, and the site’s polarizing 10-point scoring system clearly delineated the “haves” (who scored 8.0 or higher) from the “have-nots” (6.0 or lower) in a new, emerging caste system now defined by elite tastemakers rather than the unwashed masses.

Wilco was one of the site’s pet bands in the late ’90s and early ’00s, peaking with a perfect 10.0 review for 2002’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. But then the members of Wilco got a little older and a lot mellower, and their records suddenly featured a lot more guitar solos. This was something Pitchfork would not stand for.

Sky Blue Sky proved to be Pitchfork’s departure point. The review accused Sky Blue Sky of “nakedly expos[ing] the dad-rock gene Wilco has always carried but courageously attempted to disguise.” For Pitchfork, dadness didn’t just denote nostalgia — it was posited as a disorder, like epilepsy or pedophilia, that had to be concealed at the risk of a band being exposed as “passive,” “soft,” or “lackluster,” the most damning adjectives used to describe Sky Blue Sky. (By the way, the author of the Pitchfork review is my friend Rob Mitchum, who has a cameo in my book as the person who helps to get me into the jam-band Phish. This is the same guy who thinks Nels Cline is too self-indulgent. We still argue about this whenever we see each other.)

It should come as no surprise that I love Sky Blue Sky. The album contains some of Jeff Tweedy’s most trenchant songs about marriage, including the ways in which husbands suck up to their pissed-off wives by offering to do the laundry. Sky Blue Sky came out the year before I got married, and Tweedy’s meditations on domesticity (and the quiet storms that linger beneath the surface of long-term relationships) struck a chord. I welcomed Sky Blue Sky as a kind of guidebook for how to survive the next phase of my life, which is probably the best compliment you can give any work of art. Even the most polarizing aspect of Sky Blue Sky — Cline’s wonky, meandering guitar solos –sounded awesome to me. Cline channels Glenn Branca and Dickey Betts simultaneously; his playing is equal parts cerebral and badass.

But I get where Pitchfork is coming from: Sky Blue Sky is reminiscent of a classic-rock record released before the late-’70s punk revolution — a hyper-proficient, well-pedigreed soft-rock LP. It’s music about dads made by dads that would appeal most to other dads. In the view of the contemporary music press, that made Sky Blue Sky automatically suspect.

The irony of rock critics inventing dad rock in order to criticize neo-classic-rock bands for eliminating the generation gap is that the generation gap was a by-product of classic-rock mythology invented by baby boomers. Don’t trust anyone over 30, the man can’t bust our music, your sons and your daughters are beyond your command—this is the stuff of one million documentaries about the ’60s, the ones that always include the same grainy stock footage of hippie yahoos dancing in circles. (Grown-ups in the ’60s apparently hated it when young people danced in circles.)

Pop historians credit the rise of Elvis Presley with establishing teenagers as a marketing demographic distinct from adults, leading to the dawn of a new era in which pop music was viewed as a progressive force initiating social change driven by youth culture. Before then, “youth culture” didn’t exist as a concept. Modern pop subsequently became the story of forward-thinking young people embracing music performed by marginalized people — early on, it was blues and R & B played by African Americans and country and folk music associated with impoverished rural whites. Later, it was dance music derived from gay and Latin communities, and hip-hop from the poorest and blackest sections of the Bronx. All of these styles were eventually absorbed into the stew that was broadly defined as rock ’n’ roll.

The mythology of Elvis Presley was that he “invented” a new style of music by synthesizing many styles that were largely unfamiliar to white ’50s teenagers. But the contradiction of the myth is plain to see — it’s not really “new” if you are combining elements of music that already exists. Actually, I would argue that it is new, because if you don’t accept that synthesis plays a part in pretty much every great rock record ever made, then nothing is ever truly original.

If Presley existed today, he would be dismissed as derivative, because the sources of inspiration for superstars are more readily available. When Presley sang “Hound Dog,” it sounded like a revolution only if you hadn’t already heard Big Mama Thornton’s original version. That many people hadn’t heard Big Mama Thornton in 1956 is what enabled the Presley myth to persist and flourish. But it’s not just Presley who would seem unoriginal, it’s every artist who has ever mattered as a paradigm shifter. The Beatles and Rolling Stones loaded their first several records with covers of songs by Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, and Little Richard. Bob Dylan did a straight-up Woody Guthrie impression during the first three years of his career. Jimi Hendrix’s early stage show ripped off the Who. When David Bowie invented Ziggy Stardust, he was jacking Marc Bolan’s act and Lou Reed’s songwriting style. The first Ramones record sounded like the Beach Boys if the Beach Boys were from Queens and sniffed glue. Bruce Springsteen stole from Dylan and Phil Spector, U2 stole from Springsteen, and Arcade Fire stole from U2 (and Springsteen).

Of course, Big Mama Thornton deserved to be heard as much as Elvis, and it’s also true that throughout rock history, white male artists have hogged the credit for “inventing” music that had already been made by African Americans for decades. (There’s also a credible counterargument that Elvis’s massive celebrity raised the profile of Big Mama Thornton, along with countless other artists who entered Presley’s orbit, playing a pivotal role in integrating pop culture.) The problem is that we’re looking at music history incorrectly. The truth is that all music has elements of borrowing and invention. Elvis Presley became a legend because he combined different kinds of music and culture in new and exciting ways. But Elvis was also clearly indebted to many artists who came before him. He was a revolutionary, and a dad rocker.

Twilight Of The Gods is out tomorrow via Dey Street Books. Pre-order it here.