The NFL Draft is one of the most anticipated events in sports year after year, with draft projections kicking into high gear only a few weeks after the previous season’s event is wrapped up. Of course, nobody realistically knows where players will be drafted so far in advance – it’s less likely for a college football player to stay at the top of draft projections for an entire year than just about any other sport – but the reasons why a fall could happen vary. It could be due to a naturally occurring drop-off in talent during a junior season, a change of positions or responsibilities due to a coaching change, or most tragically, a potentially career-ending injury.

While there’s no certain way to protect vulnerable ACL’s or a fragile tibia or the group of ligaments around a knee, there is a way to protect college players from losing out on the hundreds of thousands of dollars that may be at risk for a top NFL prospect every time they suit up for a game. Similar to models who insure their legs, singers who protect their vocal chords, or top-tier surgeons who insure their life-giving hands, there are insurance policies available to players planning to go pro that would protect at least a piece of their future earning potential should things go catastrophically wrong.

While these policies might not be able to replace the feeling of being chosen in the first round of a draft or stepping on a football field as a pro player for the first time, they serve as a practical buffer that cushions crushing disappointment with a financial nest egg. Players taking out career protection policies is one of the more coldly practical facets of the most popular sport in America, and a complicated one at that.

The practice is on the rise though. The first time casual football fans probably heard about a high-profile case of this practice was when Ifo Ekpre-Olomu, drafted out of Oregon in the seventh round by the Cleveland Browns in 2015, collected a sweet $3 million thanks to a loss of value policy secured in advance of his senior season.

Since then, many fans understand the general concept of the situation if not exactly how everything breaks down when it comes to reimbursing an injured player for lost earning potential or draft bonuses. Most recently, Jake Butt made news when it was reported that he would be taking home upwards of half a million dollars after falling to the fifth round due to a torn ACL. But contrary to what Darren Rovell’s tweets would have you think, insurance protection for top college athletes isn’t cut and dry.

There are reports as far back as 2003 of college football players employing the strategy in their junior or senior seasons in anticipation of a big draft windfall that could evaporate because of an injury. There are two general types of protection policies available: career protection policies and loss of value policies.

The former accounts for an injury that prevents an athlete from ever playing again, while the latter simply accounts for an earnings hit due to an injury that impacts draft stock. Players can opt for one or both, as Butt did this year, for varying costs and levels of coverage.

According to ESPN, the Michigan TE secured a “$2 million total disability policy with a $2 million loss-of-value policy attached before the start of the season,” which cost him about $25,000. Yet even with this protection in place, it doesn’t mean he is automatically receiving a check for upwards of $500k as soon as the draft wraps up.

ISI, the insurance firm that handles many of these policies, also insures other top athletes such as Scottie Pippen and Carlos Boozer. Unfortunately, insurance companies’ lips are just about as tight as their wallets when it comes to policy payouts, so anyone looking to understand the rhyme or reason behind how much players eventually receive and why is left to pick through details of player statements, allusions to ongoing policy disputes from schools or business managers, or publicly available legal filings.

Comments from Butt after the draft allude to the complications of actually collecting on a policy.

Jake Butt on insurance policy: "It's really not completely accurate. There's a lot more that goes into it than what has been tweeted today."

— Nicki Jhabvala (@NickiJhabvala) April 29, 2017

For players to receive the publicized amount of money that they expect from their policy claims, everything has to go perfectly to plan and be intricately documented. If the policy was taken out a year in advance of a player’s planned draft entry for example, any pre-existing injuries or health concerns have to be revealed to the insurance company at that point. Basically, if a player shatters their kneecap in the Rose Bowl and the insurance company then deems that the player was more susceptible to the tear because of another ongoing problem they could break the entire policy (while refunding the cost to the player).

Marqise Lee, drafted by the Jacksonville Jaguars in 2014 after sliding from a first round prospect to the middle of the second round, ended up suing Lloyd’s of London for $4.5 million after they denied him an insurance payout based on failure to disclose. Morgan Breslin, who signed with the 49ers after missing more than 75 percent of his games at USC in his last two years playing, underwent similar frustrations when collecting on his policy.

Therefore, ensuring that there is specific documentation about any smaller problems during a player’s career could be the difference between a huge payout and nothing at all. The same goes for personal problems off the field, which have also been known to negatively affect draft outcomes.

Basically, unless the insurance company has definitive proof that an injury in question, and only that injury, contributed to a player’s fall and loss of guaranteed money, then there’s a chance they will deny the claim. Some coaches have even been known to communicate directly with insurers on behalf of all of their insured players to confirm that no piece of information goes unaccounted for.

A lot goes into those initial projections as well, as policies like these are only available for first or second round picks in the first place. A random player just can’t be projected to go 71st in the draft on Mel Kiper’s big board and take out a policy granting him a financial buffer should he slide to 78, as they wouldn’t have the means to pay for the policy in the first place. Due to the secrecy surrounding the wording of each individual policy, it’s hard to tell why Butt’s policy kicked in at a certain pick with a certain amount of money being paid out per pick, while others may be based off of a flat fee once a final contract is signed.

With all this money being paid out though, the biggest question at hand is where the money to pay for the policies are coming from in the first place. The biggest change in the practice of buying disability and loss of value insurance in recent years is that now it is much easier to buy either of the options, whereas in the first part of the decade, the former was pretty much the only option. Now, players can pay for the policies in a number of ways.

An example: Some schools have started dipping into Student Assistant Fund money – set aside as emergency money for student athletes – to fund player policy requirements either partially or completely. There are restrictions as to how much can be used from SAF pools which protects the funds for other athletes who have an unexpected crisis, while still letting top-tier schools tout the ability to fund policies as part of their recruiting materials.

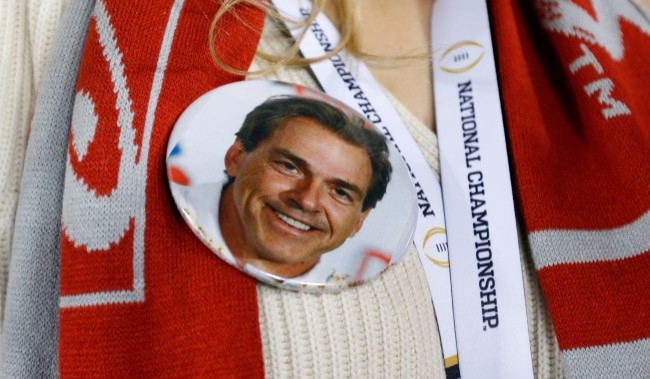

It also can be used as a reason to keep kids in school for another year – if an Alabama wideout is nervous about risking his earning potential to return to school for another season, Nick Saban can always offer up a loss of value policy to alleviate any stress that player has about the following season.

While there is a lot that people outside of the inner circle of these deals can’t know about each policy’s various intricacies, the next time reports say a player is taking home a few million dollars for being chosen in the 4th round in stead of as a top-3 pick, there’s a strong chance that’s not the end of the story.