SHOWS

Covers Books

EVENTS

FEATURED

BRANDS

TRAVEL,

DRINKS & EATS

DRINKS & EATS

Latest

Yeat And EsDeeKid Take Over Drake’s Mansion In Their New ‘Made It On Our Own’ Video

Yeat has been one of the most exciting new rap stars of the decade so far, and he's set to continue his ascent soon with the release of a new album, ADL (short for A Dangerous Lyfe). The project doesn't have an announced release date quite yet, but we do have some new music: Today (February), he teams with Liverpool rapper EsDeeKid for "Made It On Our Own." The video, directed by Director X, is a big one, as it sees the two rappers taking over Drake's Toronto home. Caleb Williams and Cole Bennett make cameos in the visual, and…

Nettspend’s Debut Album Is Coming Soon As He Gives ‘Early Life Crisis’ A New Release Date

Nettspend has been on a rapid ascent over the last few years. It started with the teenage rapper's "Drankdrankdrank" going viral on Twitter, and that was followed by his debut mixtape, Bad Ass F*cking Kid, in 2024. Fans are still waiting for a proper album, but they won't have to wait much longer, as Nettspend just announced the release date for Early Life Crisis. The project is set to land soon, on March 6. A description on Nettspend's web store notes of the album: "Nettspend's early life crisis album reflects a generation being ushered into adulthood too quickly. It channels…

Alex Warren Starts A New Chapter With The Punchy Single ‘Fever Dream’

Alex Warren is coming off a huge 2025 that saw "Ordinary" become one of the most-streamed songs in the world. His 2026 is off to a strong start, too, with a memorable performance at the Grammys earlier this month. Now, he's gearing up to launch a new era with the release of today's (February 27) new single, "Fever Dream." On the jaunty tune, Warren sings about meeting his wife for the first time: "Left the room the second that you walked in, somethin' like a fever dream / Haven't slept in weeks, I think I'm seeing things / Like our…

Anderson .Paak Links With aespa To Blend Their Styles Together On ‘Keychain’

Way back in 2022, it was announced that Anderson .Paak was making his directorial debut with a movie called K-Pops!. Now, the movie is playing in AMC Theaters nationwide, and today (February 27), .Paak has shared "Keychain," a collaboration with aespa from the movie. The track blends .Paak's hip-hop and funk sound with aespa's K-pop sensibilities. In a statement, .Paak says: "I'm excited to join forces with aespa on 'Keychain.' K-POPS! is all about connection, and this track reflects that perfectly. We come from different worlds, but we're connected by the same passion for music." aespa adds, "Working on 'Keychain'…

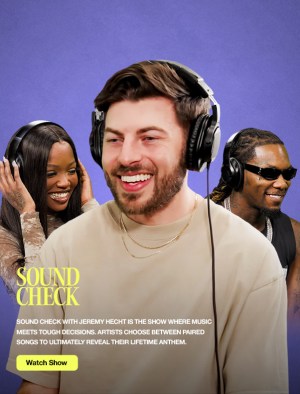

Yung Miami Is Looking For A ‘God-Fearing’ Man Worth At Least $100 Million, She Reveals On ‘Sound Check’

Uproxx's Sound Check is the show where music meets tough decisions, and along the way, we get to learn a little more about the artist. On the latest episode, the guest is Yung Miami, and during the this-or-that song-choosing game, she laid out some of the attributes she's looking for in a potential partner. Pitting Beyoncé's "Dangerously In Love" and Keyshia Cole's "Wonderland" against each other, host Jeremy Hecht asked which of the songs "feels like 'Yung Miami in love' more." After listening to snippets of both, she went with "Wonderland," explaining how her mother is a big fan of…

HARD Summer 2026 Boasts A Lineup Led By Kali Uchis, Shygirl, 2hollis, And Others

There's no shortage of standout summer entertainment options in the Los Angeles area, and that's especially true thanks to the HARD Summer Music Festival. Now, fans can start planning for this year's installment, as today (February 25), organizers have announced the lineup. The fest's lineup, as it generally is, is electronic-leaning, but there's some great stylistic variety. Highlights include Kali Uchis, 2hollis, Shygirl, DJ Snake (DJ set), Zedd, Tokischa, Zach Fox, and more. Everything goes down at Inglewood's Hollywood Park (right by SoFi Stadium) on August 1 and 2. Tickets go on sale starting February 27 at 10 a.m. PT,…

Laufey Is Expanding Her Beloved Album ‘A Matter Of Time’ With A New Deluxe Edition

It's been a big February for Laufey: At the top of the month, her 2025 album A Matter Of Time picked up a Grammy win in the Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album category (her second time being nominated in, and winning, the category). Now, she's wrapping up the month with some news: Today (February 25), she announced A Matter Of Time: The Final Hour, a deluxe edition of the album arriving April 10. It adds four songs to the tracklist and one of them, "How I Get," is out now. In a statement, Laufey says of the song: "'How I…

Lauryn Hill, Shakira, And Wu-Tang Clan Are Among The First-Time Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame Nominees In 2026

In a superlative-obsessed world, there are few, if any, bigger honors in music than getting inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame. Even being nominated is a big deal, and now a new crop of artists can add that to their resumes: Today (February 25), the Rock Hall announced the list of nominees for its 2026 induction class. This year, there are 17 nominees: The Black Crowes Jeff Buckley Mariah Carey Phil Collins Melissa Etheridge Lauryn Hill Billy Idol INXS Iron Maiden Joy Division/New Order New Edition Oasis Pink Sade Shakira Luther Vandross Wu-Tang Clan Among those, appearing…

The Best Mitski Songs, Ranked

I did not originate this theory -- I saw it on Reddit, I think, though I can't say that for sure as I haven't been able to recover the post -- but I'll share it here anyway: Mitski's career can be cleanly divided into two-album eras. There's "Embryonic Mitski" (2012's Lush and 2013's Retired From Sad, New Career In Business), "Indie Rock Mitski" (2014's Bury Me At Makeout Creek and 2016's Puberty 2), "Disco-Rock Mitski" (2018's Be The Cowboy and 2022's Laurel Hell), and "Country Noir Mitski" (the two most recent records, including the upcoming Nothing's About To Happen To…

Hotels We Love: Andaz Maui Is Peak ‘Slow Hawaii Vacation’

There are a lot of "right" ways to do Hawaii, and... I genuinely love most of them. I love the version where you go a little rugged — where the roads get thinner, there are creepers dangling all around you, and cliffs to jump off around every bend in the road. I love the surf version, too -- where the waves dictate the pace, meals are there as fuel, and the fear of offending a local in the water has me at my most courteous. But over the past few years, I've found another version of Hawaii that is tough…

The Stacked 2026 Shaky Knees Lineup Features Gorillaz, Twenty One Pilots, And Much More

Atlanta's Shaky Knees festival is routinely awesome, and they're really bringing it in 2026. This year's edition is going down from September 18 to 20 at Piedmont Park, and today (February 24), organizers shared the lineup. The Strokes lead on Friday, which will also feature Turnstile, Fontaines DC, Geese, Danny Elfman, Hot Mulligan, Snow Strippers, Ben Howard, Alice Phoebe Lou, Goldford, and Cartel. Saturday is led by Twenty One Pilots, as well as Piece The Veil, The Prodigy, Pavement, Jimmy Eat World, Blood Orange, Peach Pit, Taking Back Sunday, Minus The Bear, Wolf Alice, The Rapture, Congress The Band, Psychedelic…

PinkPantheress Is Now The First Woman And Youngest Artist To Win Producer Of The Year At The Brit Awards

PinkPantheress has made it clear that she thinks of herself more as a producer than as a performer. Now the folks at the Brit Awards are giving PinkPantheress her flowers for her production, as it was just announced that for the 2026 ceremony, she will be given the coveted Producer Of The Year Award. She'll officially receive the award at the ceremony this weekend, February 28. This makes her both the first woman and the youngest person, at 24 years old, to win the award. She said in a statement, "As the first woman to win this award, I'm grateful…

Bon Iver Is Launching The New ‘Volumes’ Archival Series With The First Edition, A Live Compilation

Bon Iver has gone through a lot of eras at this point, and now they're starting to commemorate that: Today (February), they announced Volumes. A press release describes the series as "a new and recurring archival series spanning live shows, demos, unreleased recordings and other previously unheard material, presenting the many eras and multitudes that make up 'Bon Iver.'" It also says the endeavor is "modeled after Bob Dylan's Bootleg Series and the Neil Young Archives." The full title of the first release is focused on live recordings and its full title is Volumes: One "Selections From Music Concerts 2019-2023…

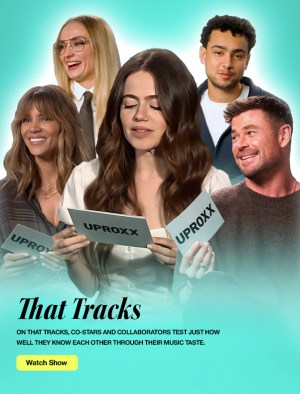

Halle Berry Makes Her Favorite Kendrick Lamar Track Very Apparent On ‘That Tracks’

Kendrick Lamar has one of the most beloved libraries in all of hip-hop, so it's hard to pick just one favorite song. In a new installment of Uproxx's That Tracks, though, Halle Berry seems to have. She and Crime 101 co-stars Chris Hemsworth and Mark Ruffalo sat down for the latest episode. In a clip, Hemsworth read the prompt, "If I'm stuck in traffic in the 101, I'm listening to my favorite LA-based artist, Kendrick Lamar. Does that track?" He added, "On certain days, for sure." Berry then chimed in, "Absolutely, hell yes," and Ruffalo added, "Would do that, too."…

A Pivotal Taco Bell Moment In Myke Towers’ Past Is At The Heart Of His New Partnership With The Restaurant

Myke Towers has become one of Latin music's biggest voices in recent years, and now he's extending his empire to restaurants. It was announced last month that he had entered into a partnership with Taco Bell. The latest product of the team-up is a new ad for the Chicken Bacon Ranch Street Chalupas, which features Towers' song "Sunblock." The collaboration actually has some personal meaning for Myke. As a press release explains, there was a day in 2015 when he was recording in Miami. All he had was $10 and no ride, so he and two friends walked to a…

Don Toliver Contributes The Spooky New Song ‘Creepin’ To The ‘Scream 7’ Soundtrack

The Scream franchise is as strong as ever: It's been three decades, and this month's Scream 7 will be the third new Scream movie in the past four years. They're getting some cool music people involved, too, as today (February 20), Don Toliver shares "Creepin'," a new song for the film. "Creepin'" is the latest of a batch of five new songs from the film debuting this month. It follows Sueco's "Rearranging Scars" and Ice Nine Kills' "Twisting The Knife" (featuring Scream 7 star Mckenna Grace), and will be followed by Jessie Murph's "Criminal" and Stella Lefty's "The Kill," both…

Summerfest’s Huge 2026 Lineup Is Led By Ed Sheeran, Post Malone, Alex Warren, And More

Milwaukee's Summerfest routinely has one of the biggest and most varied lineups in the music festival space. Organizers announced the roster for the 2026 edition today (February 19) and that remains true. The festival is set for three weekends: June 18 to 20, June 25 to 27, and July 2 to 4. Headlining are Garth Brooks; Megan Moroney; Don Toliver with SahBabii, Che, SoFayGo, sosocamo, Chase B, and Lelo; Carín León; Ed Sheeran with Myles Smith and Arron Rowe; Cody Johnson with Jessie Murph; Post Malone with Carter Faith; Muse; Alex Warren; and Jelly Roll with Tyler Hubbard. There's a…

Twenty One Pilots, Blink-182, Myles Smith, And More Lead This Weekend’s Innings Festival Lineup

Tempe, Arizona's Innings Festival occupies a unique space in the festival world thanks to its combination of music and appearances from baseball legends. The 2026 edition goes down this weekend from February 20 to 22 at Tempe Beach Park & Arts Park, and the lineup is a winner. On the music side, headlining on Friday are Mumford & Sons, and also on the lineup are Goo Goo Dolls, Myles Smith, Grouplove, Peach Pit, OK Go, Marcy Playground, Congress The Band, and Tyler Ballgame (a perfect booking, by the way). Saturday is led by Twenty One Pilots, along with Cage The…

Ed Sheeran Hops On U2’s ‘Days Of Ash,’ A Surprise EP Set To Be Followed By A New Album This Year

These days, U2 tend to take a long time between new releases, and when they do drop something, they give it a proper promotional lead-up. Not this time: Today (February 18), the legendary Irish rockers shared Days Of Ash, a six-track EP released to coincide with the Christian observance of Ash Wednesday. One of the few guests appearing on the project is Ed Sheeran, who, along with Ukrainian singer Taras Topolia, features on "Yours Eternally." Per a press release, Sheeran introduced U2 to Topolia, who wound up being the inspiration for the song, which was "written in the form of…

Taylor Swift, Morgan Wallen, And Ed Sheeran Lead The New Yearly Top Global Artists Chart

Every year, the IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry) shares its Global Artist Chart, which ranks the biggest-selling artists of the previous year. In 2024, it was Taylor Swift who topped the ranks. The latest chart is out now (as Billboard notes) and for 2025, it was once again Swift. This is Swift's sixth time topping the ranks, now having done so in 2014, 2019, 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025. (It was BTS who interrupted her streak in both 2020 and 2021.) Rounding out the top five are Stray Kids, Drake, The Weeknd, and Bad Bunny. Other notable entries…

Mac Miller Makes A Posthumous Return On Thundercat’s Endlessly Groovy ‘She Knows Too Much’

Before Mac Miller's tragic passing in 2018, Thundercat was one of his closest collaborators. Now, Thundercat has a new album, Distracted, on the way, and it includes a new song with Mac, "She Knows Too Much." Thundercat sought and received permission from Miller's estate to complete the song and feature it on the album. In a statement, Thundercat says, "I'm grateful to have spent my time on this planet with Mac. What an artist, what a spirit, what a joy to have experienced.” Léa Esmaili, the animated video's director, also said: "First of all, making this music video is a…

The Kid Laroi Will Spend This Summer Touring North America Alongside Tommy Richman

At the top of January, The Kid Laroi helped kick off a new year of music with the release of his latest album, Before I Forget. Since then, fans have been wondering if he might tour in support of the project and now we know for sure, as today (February 17), Laroi announced the A Perfect World Tour. The shows stretch from April to November. First, there's a North American run that goes until mid-June. After some time off, that's followed by UK and European shows in October and November. The artist pre-sale begins February 18 at 10 a.m. local…