Jerry Jones’ asinine opinion that there’s no link between concussions and CTE because of a lack of data is not only provably false, but underscores the NFL’s longtime stance on the matter. According to a report from the New York Times, the league relied on deeply flawed — and by “deeply flawed” we mean astonishingly incomplete — data to come to the conclusion that there was no provable link between concussions and CTE.

Per the Times, the “league formed a committee in 1994 that would ultimately issue a succession of research papers playing down the danger of head injuries” and that “for the last 13 years, the NFL has stood by the research, which, the papers stated, was based on a full accounting of all concussions diagnosed by team physicians from 1996 through 2001.”

However, the first notable (and most egregious) flaw in the data was that it did not include all recorded concussions. In fact, the Times uncovered more than 100 diagnosed concussions – at least 10 percent of the total concussions during that time period – that were omitted from the research.

In response to an inquiry from the Times, officials said teams were not required to submit concussion data, only “encouraged,” and not every team did. Like the Dallas Cowboys, for example:

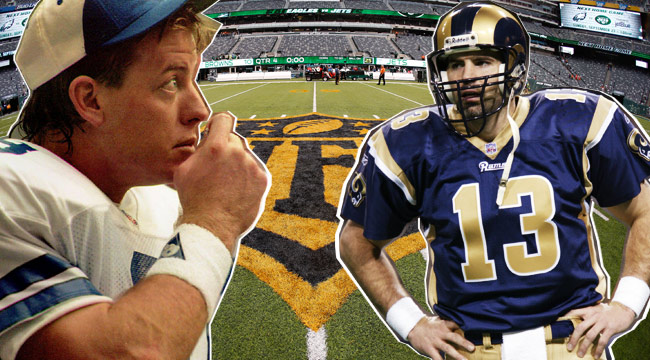

The database does not include any concussions involving the Dallas Cowboys for all six seasons, including four to Mr. [Troy] Aikman that were listed on the N.F.L.’s official midweek injury reports or were widely reported in the news media. He and many other players were therefore not included when the committee analyzed the frequency and lasting effects of multiple concussions.

Several other teams have no concussions listed for years at a time. Yet the committee’s calculations did include hundreds of those teams’ games played during that period, which produced a lower overall concussion rate.

This goes against the concussion committee’s belief that an injury, no matter how minor, needed to be included in the studies. Additionally, the committee wrote that “all NFL teams participated” in the study and that “all players were therefore part of this study.” This is obviously false.

Furthermore, some concussions that were recorded were downplayed:

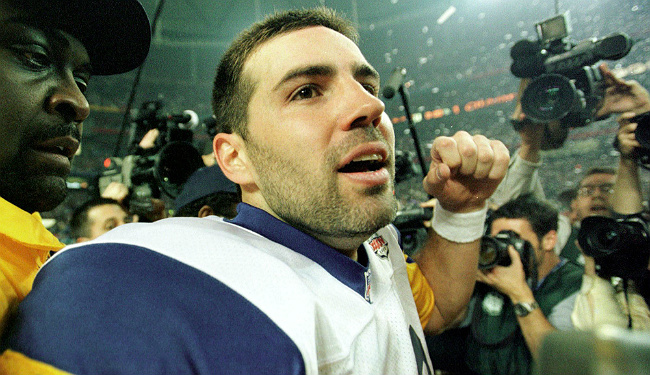

Some injuries were more severe than what was reflected in the official tally. According to committee records, St. Louis Rams quarterback Kurt Warner sustained a concussion on Dec. 24, 2000, that healed after two days. But Mr. Warner’s symptoms continued, and four weeks later he was ruled out of the Pro Bowl with what a league official described as lingering symptoms of that head injury.

In spite of all of this, the incomplete data was used for the papers. Though the league maintained this was not done “to alter or suppress the rate of concussions,” a concussion committee member, Dr. Joseph Waeckerle, said, “If somebody made a human error or somebody assumed the data was absolutely correct and didn’t question it, well, we screwed up. If we found it wasn’t accurate and still used it, that’s not a screw-up; that’s a lie.”

Clearly, there were not only flaws in the data, but in the cross-checking of it. The Times continued:

But more than a dozen pages of anonymous back-and-forth between reviewers and the committee show some reviewers almost desperate to stop the papers’ publication while the authors brushed aside criticism.

One reviewer wrote, “Many of the management of concussion suggestions are inappropriate and not founded on facts.” Another said the committee’s assertion that the league was handling concussions too cautiously was not proved and was therefore “potentially dangerous.”

The Times article also states retired NFL players “likened the NFL’s handling of its health crisis to that of the tobacco industry,” noting the common theme between the two involved questionable science. Though the newspaper admits “concussions can hardly be equated with smoking,” it still links the league to the tobacco industry through common lawyers recommending legal cases (the reasons for which aren’t known).

The tobacco industry angle by the Times is tenuous, but it plays into the theme that nothing about the NFL’s (or the committee’s) research into concussions and CTE was independent, despite previous statements:

In fact, most of the dozen committee members were associated with N.F.L. teams, as a physician, neurosurgeon or athletic trainer, which meant they made decisions about player care and then studied whether those decisions were proper. Still, the researchers stated unambiguously — in each of their first seven peer-reviewed papers — that their financial or business relationships had not compromised their work.

Above all, the Times piece further pushes the story that the NFL hasn’t done nearly enough to 1) find a link between concussions and CTE; and 2) do something about it. New discoveries on these fronts may be spun as a “war on football,” but the reality is there may not be football one day if the league doesn’t take on a bigger responsibility in correcting its previous mistakes. That’s not fear mongering, that’s a trajectory.

(Via the New York Times)