The accolades and the respect are unending for NBC’s late-night alums. Johnny Carson defined what late-night comedy could and should be. He then passed the baton to David Letterman, who promptly broke a ton of rules and instilled an aversion to authority and fakeness in ’80s and ’90s comedy nerds that’s still in the DNA of almost every talk show host today. And then Letterman gave that baton to Conan O’Brien who found his own rules to break by delighting in the absurd. These hosts — as well as Leno, Fallon, and Meyers — have made a huge impact on television, but they’ve also obscured NBC’s other late-night efforts.

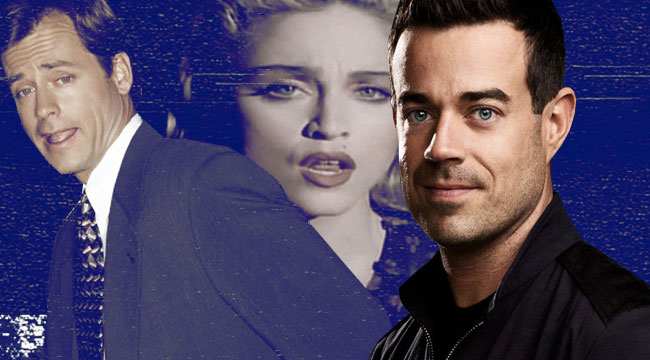

Airing at 1:30am for almost 35 years, NBC’s less-revered options have a legacy all their own that touches the worlds of music, comedy, and the catch-all that is late night. Over the years, the shows in that slot have collectively created a tradition apart from their lead-ins, one that has influenced the current inhabitant of that time slot, Last Call With Carson Daly. That show has managed to find its way and stand out as a surprisingly charming and illuminating bit of counter-programming at a time when late-night viewers might be eager for something that tries to entertain and inform them at a different speed and with a different focus.

The Birth And Death Of Friday Night Videos

The two dominant halves of Last Call are doubtlessly music and conversation with each being represented by the now impractical-seeming timeshare arrangement that occurred from the late ’80s through the early 2000s when Friday Night Videos and Later alternately occupied the 1:30 slot. But while Friday Night Videos represented NBC’s biggest commitment to music in late night, it actually began much earlier with Saturday Night Live and The Midnight Special. Those two shows, with their reliance on live musical guests and concert footage, also connect to Friday Night Videos through Dick Ebersol, who helped develop and later produced SNL, ran Midnight Special, and dreamed up Friday Night Videos in 1983 after seeing a report on the CBS Evening News heralding the MTV boom.

Xeroxing someone else’s bold idea to bring music videos to NBC wasn’t the most awe-inspiring achievement, but Ebersol believed he was doing a service to MTV with Friday Night Videos. “They’re in 15 percent of the country. We’re in 100 percent. This will whet the appetite,” he told the Associated Press ahead of the premiere. Was that braggy chest puffing by an executive that was charged with talking up his latest creation? Sure, but it was true and Friday Night Videos‘ ability to deliver music videos to the masses when the masses wanted (but couldn’t always have) their MTV is what gives the show any kind of legacy. It’s also what gave it any kind of relevance, but that faded once MTV’s reach expanded.

By the ’90s, the use of guest hosts (a list that includes Hulk Hogan, the cast of Facts Of Life, Dr. Ruth, David Lee Roth, and Bob Costas) had been retired in favor of more permanent hosts like Daryl M. Bell, Tom Kenny, and Tonight Show bandleader Branford Marsalis. Comedian Henry Cho followed Marsalis in 1994 for what was supposed to be a six-week run prior to the end of the franchise, telling Uproxx, “they wanted me to use the time to get my feet wet at hosting.” But a funny thing happened: the show re-found its audience and its purpose and managed to stick around as Friday Night began losing the “Videos” figuratively and near literally.

Cho was teamed with actress Rita Sever, and for the next six years, the show eeked along, mixing movie reviews, a small selection of music videos, celebrity interviews, and performances by musicians and comedians. There was also, for a time, a monologue and sketches that Cho wrote with show writer Jim Hope and help from friends Don McMillion and Carlos Alazraqui.

In 1996, Cho left the show to appear in McHale’s Navy leaving Sever as the solo host. Sever kept things light and fun and took the show to some interesting places with remote segments, like when she toured the space shuttle. Nonetheless, the show folded in December 2000 after 17 years on the air leaving a front-loaded legacy and a small hole in NBC’s schedule.

The Different Sides Of Later

The idea of putting on a comparatively sedate longform interview program following the quirky wildness of Late Night with David Letterman dates back the start of Letterman’s NBC run in late night in 1981 when NBC offered the 1:30am time slot to Tom Snyder, the occupant of the 12:30am time slot Letterman was about to take over. Snyder, rejected it, leaving the network, and NBC gave NBC News Overnight an 18-month until its 1983 cancellation.

In 1988, a year before his ascent as head of NBC Sports, Ebersol created another NBC late-night show, one hosted by Bob Costas, a sportscaster with whom he had initially worked with on an episode of Friday Night Videos. The resulting show, Later, relied on Costas’ easy rapport with actors, athletes, and other figures in the form of engaging and thoughtful interviews that offered more than the typical late night snapshot. The show was a gamble — straying from the idea that the later the hour the more youth-focused a show needed to be — but it paid off with Costas winning an Emmy and putting out six years of intelligent late-night television before he decided to focus on his work with NBC Sports following the network’s success in getting the rights to air Major League Baseball games.

In Costas’ absence, NBC turned to Greg Kinnear in 1994, then a smarm-dispensing comedy machine over at E! as the host of Talk Soup. At the time, the 30-year-old Kinnear was heralded as a prospect for NBC that could stand at the ready to replace Conan O’Brien if/when the network decided to move on from its initial Letterman replacement — a distinct possibility in those early years when the network torturously refused to commit to O’Brien beyond 13-week contracts. Kinnear even joked about it when he was hired.

With Kinnear as host (initially pulling double duty as the host of Talk Soup), Later fell in line with late-night comedy norms but lacked the intriguing depth of Costas’ version and failed to stand out in the shadow of the more comedically daring work being done by O’Brien as he settled in to Late Night.

With more time, maybe Kinnear could have lived up to his potential. But by 1996, with O’Brien’s cult fanbase swelling and Leno cemented as the late-night ratings king, Kinnear smartly sensed that acting was a better path for advancement and left Later. Guest hosts, including Sever, and a permanent host in Cynthia Garrett followed, but by the start of 2001, NBC was ready to move on just as the network had with Friday Night Videos. A stand-up comedy show called Late Friday and SCTV reruns — apt since Friday Night Videos had taken SCTV‘s time slot in 1983 — followed before Last Call with Carson Daly was given the time slot in 2002.

Finding Its Way

Compared to his peers, Carson Daly’s show has been under-hyped and under-examined, especially considering it’s been on the air for 16 years (making it the longest running late-night show on broadcast TV) and endured a lot of twists and turns. But while the lack of buzz and attention might bother some, it doesn’t seem to bother those on the inside. “We’re not in that late-night war and I’m very grateful for that,” says Stewart Bailey, an executive producer on Last Call.

A Daily Show producer from 1996 to 2005, Bailey joined Last Call in 2010, sidestepping early iterations when the show saddled Daly with a band, a studio, and the task of reading a comedic monologue nightly. Bailey also missed out on the actual late-night war when NBC’s decision to move Leno to primetime after his “retirement” from The Tonight Show failed, causing the network to consider bringing Leno back to 11:35, which would have pushed O’Brien and Fallon each back a half hour and potentially cost Daly his job.

Looking back, Daly handled the situation about as well as anyone could. While NBC’s TV chairman Jeff Gaspin was omitting Daly from remarks that made it clear that the goal was to keep Leno, O’Brien, and Fallon in the lineup, Daly was saying all the right things. He even made an appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live to joke about his weird afterthought status and ask Kimmel to give him his show. The moment — equal parts clever and sympathy-inducing — demonstrated that Daly could take a joke and hang with the rest of late night when it came to being funny. By that point, however, Daly had long since let go of any desire to be like the rest of his peers. With Leno, Conan, and Fallon in front of him, all sitting at desks in a suit and tie, Daly rebooted his show in 2009 before the start of the “war,” telling GQ in 2010, “I always liked Dave Attell’s Insomniac. I liked that feel of him walking the streets. That’s where I belong. We have a small staff. We’re not even a real late night show.”

Daly’s vision and desire to hit the street and eschew the setup that most other late night shows embraced meshed nicely with Bailey’s experience as a field producer (among other roles) on The Daily Show. Last Call was on its way to carving out a nice niche as a small but cerebral arts show focusing on casual interviews and look-ins at trendy rock clubs but their progress was threatened by Carson Daly’s inextinguishable likability and another opportunity within NBC.

Team Lift

Ambition is a key characteristic in all late night talk show hosts and Daly hasn’t been immune to it. There were reports that he lobbied for the 12:35 slot after Conan graduated to The Tonight Show and assumptions that he would have happily moved up to replace Fallon when he did the same. But when the Today Show came calling, the threat of a Daly exit became real and Last Call veered toward its end once more.

In a 2013 press release, Daly announced that he would stay on as an executive producer for Last Call. A “transition” plan was in the process of being constructed for Last Call, but no one on the outside knew what that meant. Most probably assumed that Daly would be a name in the credits for the sake of continuity or help pick a successor, but few likely imagined that he would decide to remain while decentralizing the role of the host on the show to serve as a sort of MC.

With Daly’s plate full, Bailey and head writer/supervising producer Brett Webster conduct interviews while off camera. Music producer Davis Powers supplies the musical guests, leaning on his years of experience and the relationships he’s forged with venues, labels, managers, and artists to keep the fresh flow of talent steady. And of course, there are other producers, editors, writers, and support staff that come together with them to create the show. But the team approach and Daly’s lesser on-screen role doesn’t mean he’s detached creatively from the show that bears his name.

“We talk a lot about what’s going to be on the show,” says Bailey, adding that “Even though we have less access to [Daly], we’re still in touch with him and it’s an extension of the kind of show we decided years ago we wanted to create. Which is just go all in on storytellers, music, and interesting people. Some of whom you’ve heard of and some them you haven’t.”

Roots In The Past And Eyes On The Moment

According to Bailey, Last Call is looking for a very specific kind of guest.

“We don’t really have a show that we compete against, so we’re not counter-programming to anything. We’re just using our own test of ‘Do we find this person or this project interesting?'” Bailey adds that he’s as excited to talk about an indie film that faces a challenge to get people’s attention as a big-budget blockbuster. It’s an approach that Bailey says the show arrived at after a lot of “trial and error.”

Pursuing people that are of interest to you only goes so far when your primary goal is an interesting conversation, however. You’ve got to allow for surprises and be a little unprepared and willing to go down a conversational rabbit hole with a guest.

“What’s nice about a longform interview where you don’t want to go through… it’s not like a job interview. It’s not like you’re on a speed date, where you’re trying to cover a lot of ground in a little bit of time. You want it to be a hang, where unexpected things emerge.” According to Bailey, the lack of an audience and the intimate setting (usually in a bar or restaurant that’s blocked off for them) helps accomplish that goal. The same goes for keeping things fresh and avoiding pre-interviews for sessions that often stretch beyond a half-hour for a finished product that runs for a fraction of that time.

Bailey acknowledges that, in late night, that’s not the kind of interview that’s typically available. It’s five minutes and out with a funny and polished story and a bit of congenial chit-chat unless the host and the guest have the kind of rapport that allows for something fun and unique in that short space of time.

The rejection of the typical late night interview is, of course, a tradition for Last Call‘s timeslot with Costas’ Later applying the same technique of just letting guests talk until the meat of the conversation revealed itself along the way. Bailey acknowledges that connection, saying it’s “not unintentional” while praising the way the audience discovered something new about the guests on Later — a rarity in this moment of social media and overexposure.

Last Call‘s efforts to break new music and artists are a point of pride for both Bailey and Daly. (Halsey, 21 Pilots, Ed Sheeran, and Kendrick Lamar are among some of the musicians to get early breaks on the show.) And that want to give music acts broader exposure is definitely in step with what Friday Night Videos sought to do in the early going. But they didn’t want to alter the pure aesthetic that comes from hearing live music in a club.

“They’re not coming to our studio and adapting to our world, we’re going to their world and it shows,” Bailey says before telling us that the show feels like they have the music side of things down. “These fans know all these songs, these are all ticket buyers. This isn’t a television studio, this is [music] in the way that people want to enjoy it. We have a very small footprint, which means that the venues will let us come and shoot because we don’t disrupt anything. We don’t set up lights. We just record it.”

The Talk Show Of The Future?

Bailey won’t take the bait when he’s asked if Last Call should be a model for other shows. He’s not a pundit and he’s worked within the realm of other shows and knows that each one, despite appearances, is its own unique ecosystem. But he does believe that every show evolves, pointing to the long road Last Call has gone down to get to a place where they feel comfortable and confident with the show that they put out.

But while that’s a great North Star to use as a guide — perhaps, the healthiest kind to chase in any kind of creative endeavor even if it’s often perceived as an anathema to the business side of things — it’s not why Last Call should be emulated.

While Bailey defends the show against the suggestion that they avoid political conversations, offering a list of journalists and media personalities that have been on the show, it’s not like Last Call features a host pounding on his or her desk while delivering fiery rants. That’s common in the age of Trump. Not a bad thing. Just a common thing. But common should be the enemy of all late night shows. Especially when it seems like the only shows assured a legacy are the unique ones.

Politics has late night (and, really, America) by the throat. With that accepted, counter-programming and subtle reminders of a bigger world with portraits of people that aren’t reduced to sound bites or political views are a thing to be treasured. Same as shows that skip past the serious whenever possible to deliver a bit of silliness.

While longform interviews with interesting artists and intimate performances from musicians may not represent late night’s future (even if it sounds like something tailor-made for younger audiences that aren’t wrapped up in the formality and history of late night), it’s a welcome return from parts of its past and a nice option to have when the political noise becomes unbearable. And it’s waiting for you at 1:35 in the morning.