The first and last time I ever spoke to David Berman, our conversation ended on an upbeat note.

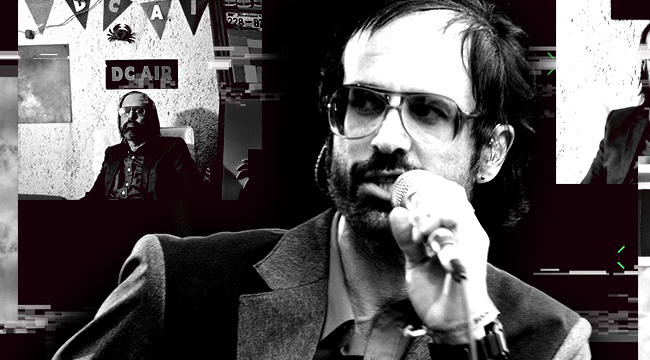

It was May. We had just talked for 90 minutes about his first album in 11 years. After putting out six LPs as the leader of Silver Jews, the 52-year-old singer-songwriter had a new project, Purple Mountains, and a beautiful and impeccably crafted self-titled record that eventually garnered rave reviews upon release in July. While Berman had a reputation for being averse to touring, he was planning to go back on the road this summer. We even made plans to meet in person backstage at his show in Minneapolis, which was supposed to take place a few weeks from now.

Berman noted that while he played only about 100 shows with Silver Jews over the course of nearly 15 years, he was going to play 25 gigs on this upcoming tour alone.

“I can’t wait,” he said. “I’m ready for my solitude to end.”

Berman and I had been emailing back and forth at that point for about four months. He first reached out to me in January, because he noticed that I tweeted a few times about liking Silver Jews. “More often than I’d like to admit I search Twitter for ‘Silver Jews,’ looking for a shot of courage, lurking for a good sign,” he wrote. “And more than once you were my signal to keep going. A few critics like a few albums but you’re the only writer I’ve read that takes it as a given that the music is good.”

I was stunned to hear from him for a couple of reasons. First, I had interviewed numerous indie musicians who tried to communicate with Berman over the years, with varying degrees of success. He had basically been a recluse ever since publicly disbanding Silver Jews in 2009.

Second, he was wrong about me being the only music writer who loved his music. He couldn’t have been more wrong about that one, in fact. The rapturous response to Purple Mountains — a record that many fans surely doubted would ever come to fruition — was evidence of that.

I would hardly count myself among the most devout Silver Jews fans. I own and cherish his records, and even quoted one of his songs, “Trains Across The Sea,” in my first book, Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me. (“In 27 years, I’ve drunk 50,000 beers,” which seemed to sum up my 20s better than any lyric I could think of.) Other songs of his are lodged in my brain for how he described ordinary things in extraordinary ways, like “the jagged skyline of car keys” from “Black and Brown Blues” or when he asks “can you summon honey from a telephone?” in “Smith & Jones Forever.” But I’ve met people who can quote his lyrics like a preacher citing Biblical verse. More lyrics than I could ever repeat on demand, that’s for sure.

When news broke late Wednesday afternoon that Berman had died suddenly, you could see those people invoking his words like serenity prayers. Some of them were peers, including fellow singer-songwriters like John Darnielle and Craig Finn. In the ’90s and ’00s, Berman had earned a reputation as perhaps the finest lyricist of his generation, delivering his prose in a deadpan drawl against sparse, introspective country-rock jams accented with exploratory solos by his friend and frequent bandmate Stephen Malkmus. In later iterations of Silver Jews, it was his protege, the excellent Americana guitarist William Tyler.

Berman was the rare lyricist whose words could actually stand apart from his songs as literature. He often doubted his abilities as a musician and singer — wrongly, in my view — but there was undeniable music in his words. They would sing to you, even if you just read them on the page.

Take this verse from “Maybe I’m The Only One For Me,” the last song on Purple Mountains — the final album he ever released, if you can wrap you head around that:

Bended knee, honeymoon

Nursery, another soon

Into my mind, the thought begins to seep

If no one’s fond of f*cking me

Maybe no one’s f*cking fond of me

Yeah, maybe I’m the only one for me

You can find everything that made Berman stand out as a writer in that passage, most importantly his ability to communicate inner pathos with a mix of brutal honesty and sardonic wit that transformed his pain, at least on record, into a work of art.

Berman took his art seriously enough to stop putting out music for more than a decade because he worried about his material growing stale. For Purple Mountains, he talked about how hard he worked to make every line just perfect, so it never seemed phoned in or just plain phony. But from what I could tell, he didn’t take himself all that seriously. Throughout our conversation, he was self-effacing to the point of being self-defeating.

Initially, he flashed some bravado about not caring about whether he would ever be remembered. If the world had moved on from him in his absence, so be it.

“I’m not the type to demand affirmation or to worry about that I’ll be forgotten,” he insisted. “I’m more the type to dare the world to forget me.”

But I didn’t really believe that. After all, he had reached out to me, a stranger, because I said a nice thing or two about him in a public forum. From what I could tell, he really wanted someone, anyone, with whom he could connect.

The more we talked, the more that bluster faded away. He was proud of the Purple Mountains record, but he seemed unsure about how it would be received. He expressed regret over the album’s first single, a melancholy ballad with a jaunty rhythm called “All My Happiness Is Gone,” because he didn’t want to be perceived as a sad sack.

But more than anything, he doubted that anyone actually liked his music. He even did a roll call of indie musicians who had name-checked him in interviews; it was a list he had apparently kept close tabs on in his mind.

In the latter part of our interview, I was basically giving him a pep talk about how respected he was, and how his music had been overlooked in part by it being unavailable on streaming platforms for many years. But I assured him that once the typical indie-rock fan born in the 21st century had a chance to hear albums like The Natural Bridge and American Water, that they would become quick converts. To me and others, he was part of a songwriting continuum that includes Lou Reed and Townes Van Zandt — all-American iconoclasts who specialized in writing about outsiders from both the big city and the plains of middle America. Berman found his own space somewhere between all of that.

“It’s amazing to me that I’ve be able to subsist all this time on Drag City royalties,” he marveled as our interview wound down. “I still don’t get it. It still seems like it must be rigged. I often imagine a castle in Lichtenstein with pallets of Silver Jews CDs, where some multi-millionaire’s doing an experiment to help my esteem.”

.

Even in conversation, David Berman found a way to express his darkest fears like a clever storyteller.

I sensed that he wanted to keep talking, but it was the end of the work day, and my wife and children were waiting to have dinner with me upstairs. Berman didn’t have anyone waiting on him — he had recently separated from his wife, and he never had any kids. He was living at the time in a spare room at the office of his record label, Drag City, in Chicago. He said I was the only person he had to speak with that day. But still, as we wrapped our conversation, I felt he was in a good place. I told myself he was in a good place, at any rate.

When someone dies suddenly, you make a wish about the things you might have said. I think this stems from the belief that lonely people can be made to feel less lonely when others tell them how much they’re loved and valued. I’ll always be grateful that I was able to express to David Berman precisely that sentiment during our brief time together. But I also know that some people are so profoundly alone that even being with other people doesn’t make them feel any less alone.

I know that I’m far from being the only person who told David Berman how much he mattered to all of us in the final months of his life. I just wish hearing this would’ve ultimately mattered more to him.