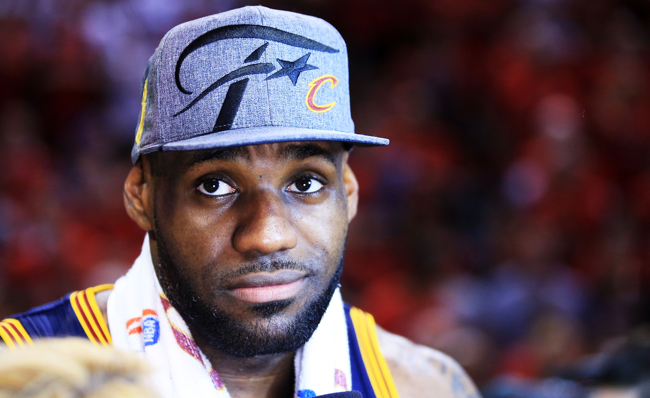

For a large subset of the basketball-viewing public, LeBron James has been gleefully excluded from the concept of “liberated fandom.” He’s a love-him-or-hate-him kind of player, and for those on the latter side of the fence, he elicits the type of disdain usually reserved for only the world’s most despicable pariahs. Just look at how fans greeted him upon his arrival in the Bay Area.

They don’t see a 6’8, 250-pound athletic specimen who can play all five positions and who regularly dominates his opponents in ways we never previously imagined. What they see is a flopping, coach-killing, crab-dribbling complainer who uses new technology to passive-aggressively berate his teammates, a world-class pretender who shies away from the big moments (and not even a mountain of evidence to the contrary could disprove that last part in their eyes).

This has always been his cross to bear, and if we’re being honest, he’s brought a lot of it on himself. The LeBron James management style over the years has been a grab-bag of exclusionary tactics and subtle barbs aimed at no one in particular that still somehow always manage to find their mark. His decision-making, at times, has also left something to be desired, whether that includes one particular capital D decision, the now outrageously-premature promise of “not one, not two,” but a seemingly limitless number of championships for the city of Miami, plus a laundry list of other things.

He’s heard all these criticisms before, and Steph Curry’s ascendance only further complicates matters. When the 2016 NBA Finals tips off on Thursday night, it will mark LeBron’s sixth-consecutive Finals appearance, and his seventh overall. It’s a truly remarkable achievement by almost any measure. But like everything else with LeBron, there’s a big caveat. So far, he’s just 2-4 in the NBA Finals. It’s a record that likely already affects his stature on the list of all-time greats, a dark smudge on an otherwise extraordinary career resume that will be difficult to overcome as he grows older and the prospect of winning multiple titles down the line grows dimmer with each passing season.

What’s more, he has been undoubtedly the player most affected by the enormous shadow Curry has cast over the league these past two seasons. LeBron has long been considered the best all-around player in the game, and you wouldn’t be carted off in a straight-jacket by a group of orderlies in boiled whites if you still wanted to argue that today. But a second-straight Finals loss to Curry and Co. with a fully-healthy Cavs team would make it impossible to hold that distinction any longer.

Which brings us to his whole ostensible reason for returning to Cleveland to begin with: to bring home a title to his long-suffering franchise. It’s been more than 50 years since the city has won a championship of any kind, and LeBron has — in many ways unfairly — been heralded as its savior since his arrival as an 18-year-old high-school phenom. But he’s always embraced those expectations, especially upon his prodigal return in the summer of 2014 when he reaffirmed his commitment to that ultimate goal.

But ever since his return, the specter of his departure has loomed large over both the organization and its jittery fan-base. LeBron is a shrewd businessman and, make no mistake, cold and calculating in his decision-making. It’s why he keeps signing one-year contracts with the Cavs. Purportedly, it’s about the rising cap and the opportunity to maximize his earning potential over the next couple of years, which is more than a little absurd given the amount of money he’s raked in already over the course of his career via numerous revenue streams.

Arguably, its primary purpose is to keep Cavs brass on their toes in terms of doing everything possible at every juncture to keep a championship-level roster intact and add new pieces as necessary along the way. Not that LeBron James would ever really think about leaving Cleveland again. His reputation might never recover. Still, he likes to dangle the possibility of it over everyone’s heads to keep getting what he wants, which — to be fair — is what he believes is best for the organization to begin with.

Even if LeBron James never wins another championship, he’d still likely go down as one of the top five players in NBA history thanks to the mind-boggling list of records, individual accolades, and statistical accomplishments he’s accrued so far. But never winning a championship for Cleveland would be a permanent blemish on his otherwise legendary career, one that would haunt him for the rest of his days.

The Eastern Conference got better this season, but not by much. Aside from a pair of lackluster games in Toronto in recent weeks, the Cavs have once again proved that there isn’t that much parity at the top. The way they’re currently constructed, the Cavs could probably steamroll their way to the Finals for the next few years. The test of these Finals, however, will be whether they can actually compete with the Western Conference elite.

Yes, the Cavs are better than they were last year, finally healthy and finally firing on all five cylinders. But these Warriors are also exponentially better than they were last season and have to be feeling more confident than ever after pulling off one of the great comebacks in playoff history. If LeBron can’t lead his Cavs to a title this spring, he might have to resign himself to the fact that not only might he never win another one as long as Curry and the Warriors are around, but his days as the world’s best basketball player might be behind him.

A win over the greatest regular-season team in NBA history, however, could change the narrative dramatically. LeBron would be back on top and will have re-asserted his will as the best all-around player on the planet.

Then again, if Cleveland wins, it might be precisely because they’ve adapted to the formula put in place by the Warriors. Earlier this postseason, the Cavs suddenly transformed into Warriors-East, launching three-pointers at a hysterical historic rate and deploying a tactically-smaller group they hope will offset Golden State’s vaunted “Death Lineup.” If Cleveland is able to beat them at their own game, it’ll only reinforce the Warriors’ central role in the evolution of the game.

That won’t matter much to LeBron James, who’ll take it any way he can get it at this point. A 3-4 record in the Finals will feel a lot better than 2-5. Fair or not, another Finals loss would significantly reduce his chances of going down as the greatest basketball player of all time, regardless of his career-long statistical dominance over so many different aspects of the game.