No one would choose to be synonymous with a pandemic. Such a label makes them a pin in history representative of an acceleration point, a shorthand of when things got serious. Rudy Gobert, running his hands all over the phones and recorders on the table in front of him, not seeing in that final press conference that the window for levity had shut, became such a shorthand. And because Gobert, seated on a podium in his uniform at work, is a representative of a much larger entity, in the blink of an eye under the collectively furrowed brow of those watching, the NBA grew just as instantly intertwined with a global pandemic.

In the slow-motion minutes and fever dream cadence after Gobert’s failed prank, there was a rare glimpse into the real-time response of a company weighing its options. Snippets of information were coming out of the sports media in Chesapeake Energy Arena: OKC players being waved away from the emptied visitors bench by panicky referees, both teams sequestered in locker rooms, and with every backward shot Rumble the Bison attempted from half court to a crowd teetering between confusion and alarm, there was a growing impatience from those watching from outside, piecing it all together, to call the game.

That same night in Sacramento, with the Thunder-Jazz game yet to be officially postponed, Kings players took the floor. Within a few minutes, it became clear that New Orleans players would not be joining them. News leaked out of Oklahoma City that a Jazz player had tested positive for COVID-19 earlier that day. Courtney Kirkland, set to officiate in Sacramento, had worked the Utah-Toronto game two nights prior. Pelicans coach Alvin Gentry told officials his team would not play, and players and staff quickly returned to their hotel.

With both games postponed, there was growing concern over what was actually happening and how initially widespread things were within the league. All 30 NBA teams could be linked together in the week preceding March 11, well within the incubation period of the virus, not to mention the staff and media — like those who were stuck inside OKC’s arena as reports began to suggest that the infected player in question was Gobert, whose fresh fingerprints were all over the recorders and phones in their hands and pockets — surrounding each team.

The NBA’s handful of early missteps are softened by hindsight and conflicting information. The league didn’t postpone the March 11 games or the season despite the World Health Organization declaring COVID-19 a pandemic earlier that same day and its China office having already been closed, its colleagues there under the same lockdowns that would soon hit the United States. But there were not yet clear directives from American public health officials on restricting public gatherings. In cities where NBA teams play, only San Francisco had declared a moratorium on gatherings of over 1,000 people. The league knew Gobert had been tested and still assumed the game could continue as they awaited results and later, sixty percent of Oklahoma’s available tests for the virus were rushed to test players, team, some arena staff and media following guidance from the Oklahoma Heath department, despite the fact that it was not yet clear how many tests were available within each state and when they could be replenished.

As the situations in Oklahoma City and Sacramento developed, decisions needed to be made quickly. And after the dust of those first few days settled, the league righted itself by realizing that, like it or not, it had arrived in the eye of the pandemic making landfall in the U.S. The NBA suspending its season outright in the days that followed forced both other pro-leagues to follow suit and individuals who still viewed COVID-19 as a distant threat to sit up and pay attention. It is strange, but it is not a stretch to say that Gobert and the NBA were arbiters of the pandemic, mitigating its impacts and proactively responding before the government did.

“We’ve certainly never been through anything like this,” the NBA’s President of Social Responsibility and Player Programs, Kathy Behrens, says over the phone from her home in New York, “but we have been through other situations, unfortunately, that have required us to figure out the right ways to connect with our fans, connect and support our communities, and make sure that our employees and players and teams were all safe and doing all they could to stay together, whatever the crisis might be.”

In her twenty-year tenure with the league, those crises have ranged from natural disasters to terrorist attacks, but never a pandemic on the scale of COVID-19, which Behrens says “requires a different way of thinking and a different way of responding.”

As unprecedented of a situation as it was for the league to be involved in, the NBA’s organized response came together within eight days — sooner if you count its first public health PSAs and the independent efforts of its players to subsidize lost wages of arena workers — due to the launch of NBA Together. The program took some of its framework from ongoing league initiatives, like NBA Cares and Jr. NBA, but its focus was far more targeted on public health messaging.

These were commercials with players and alumni, urging hand washing and social distancing long before similar missives were coming from municipal or federal government. They soon evolved to include encouragement to stop the spread of false information as much as the coronavirus. But as statewide stay at home mandates caught up, Behrens recalls, “I think when we all went into the shelter at home protocol, we realized that there was going to be more to our work.”

It is rare for an emergency to affect so many at once worldwide, but this unwanted, alarming commonality was the unifier for the league’s immediate response.

“As you look around the world, we have so many communities impacted by this virus, and so what could we do to deliver those public safety messages?” Behrens asks. “What could we do to supply support to the front line healthcare workers and other essential personnel, first responders? What could we do to stay connected to people, and communicate and use whatever means were at our disposal? Usually we have our games to do that, but we don’t have those right now.”

Unfortunately, the league had firsthand resources when it came to the real-time education it could offer its audience on the coronavirus. Gobert and Donovan Mitchel were two of the first high-profile cases confirmed in the U.S., with Marcus Smart, Kevin Durant, Christian Wood, and unnamed individuals within other franchises following. The entire Raptors roster and staff went into Canada’s federally-mandated 14-day self-quarantine given their contact with Gobert and the Jazz. Almost all of the players who were publicly confirmed as testing positive offered PSAs and Q+A sessions on their social media for fans, sharing reports on their health and science-based information on COVID-19, all while urging viewers to stay in and stay safe.

There were also lessons that the league was taking from its China offices.

“We have close to 200 people who work in the NBA China offices,” Behrens says, “and so we understood what they were going through as soon as things really started to get out of control. As we started to see the spread of the virus, we really focused in those early days on the public health messaging, and those have evolved certainly.”

In many ways, the pandemic has put us on a collective course. Those with jobs that supported remote work quickly fell into a new routine. Kids stayed home from school and most of the world’s population followed some form of lockdown measure, as frontline workers remained some the only people to maintain “normal” routines, but faced challenges that were anything but. When developing its offerings, the NBA took all this into account.

Its 2K Tournament gave fans the chance to engage with players real-time, for prolonged stretches, while extended initiatives like Jr. NBA at Home promoted physical and mental health through exercises that could be done in small, enclosed spaces with little to no equipment, led by NBA and WNBA players, coaches, and alumni. First designed for kids who couldn’t play in leagues or at school, these drills expanded to include anyone, with varying degrees of skill and difficulty. A HORSE tournament followed, offering a form of gameplay, albeit adjusted for remote and technical constraints, in the broadcast slot where games once sat. The league was able to take these varied offerings and schedule full days of programming. While keeping its audience entertained and informed, it was also keeping them home and safe, because in some states where fans were watching, COVID-19 had arrived but was not yet rampant.

Behrens is intuitively cognizant of this balance, trying to offer entertainment that also could use their platform to push best practices and raise money for relief efforts. And it’s all coming through platforms that the league and its fans have utilized to a degree, but not to this extent. Behrens acknowledges that they are “learning every day” when it comes to what works and what is less successful in reaching a captive, but remote audience.

“TikTok is not necessarily the best place to do public services messages,” Behrens says with a learned, knowing laugh, “but it’s a great place to let people have some fun and release some of that nervousness.” Instagram and Twitter have proven to be good avenues for engagement, especially in giving their audience accessibility to medical professionals, like former U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy, to answer questions related to COVID-19 where misinformation has been rampant. “We’re just constantly trying to evolve,” Behrens says.

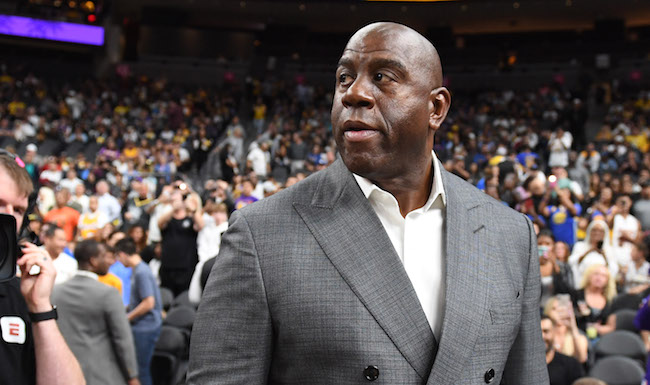

This evolution has most recently shifted to highlight disproportionate infection and fatality rates amongst those most vulnerable, like black and hispanic communities, where the NBA has significant reach. Utilizing its longstanding partnerships with organizations like the National Urban League and the NAACP, as well as local, community-based organizations, the league is keen on ramping up its health and economic messaging, spotlighting issues of social awareness through its most prolific voices. Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar were two of the first who featured as advocates.

“And that affects both the criminal justice system as well as those who are historically marginalized, and how do we both raise awareness but also take action to support those communities? That’s something we’re very focused on.” Behrens says. “This virus has hit the black community in really significant and profound ways. We can’t ignore that.”

Aside from its ongoing financial contributions (the league has raised over $78 million internally so far to support in relief efforts and frontline response to COVID-19), some of the most profound and affecting resources the NBA has are its players. With huge, organic platforms and reach most are already familiar in using, players were also the first to be touched by COVID-19, if not directly, then in the small circle that they make up. It was natural for player-led initiatives to accompany those the league was rolling out. Kevin Love brought his concerns around isolation and mental health forward and helped to shape the mandate of NBA Together. Steph Curry’s interviewed with Dr. Anthony Fauci, a few days after Donald Trump sidelined him during his daily press briefing, and brought the first plain language conversation around coronavirus concerns to many.

Behrens stresses that “it takes a village” in terms of the logistical organization of the league’s efforts thus far, but that “players bring it to life.”

“Their voices, the power of the platform they have, the commitment they have to want to engage in this way, and the support from them has just been incredible,” Behrens says. “I think that’s one big benefit we’ve had. NBA players have historically, and by historically I mean the last number of years that social media has been so prevalent, they have always embraced that way to connect with their fans and now they see it as even more important.”

There’s a snowball effect to this as well, with 58 million video views across the league’s social platforms, 40 unique PSAs, individual teams starting up their own together programs focused on the unique needs of their markets, and players coming forward everyday with new ideas.

“There are some guys who keep saying, ‘Oh, I have another idea!’ And so we’re taking as many of those ideas and trying to turn them into program elements as we can,” Behrens says. “I think they realize both individually and collectively that they can have a tremendous impact and that they can help people. That’s something that they are committed to. I love that it’s NBA players, it’s WNBA players, it’s coaches, it’s legends, it’s team executives. This is everybody.”

As widespread as the pandemic has grown, saturating every media outlet, there are many who, either inundated with conflicting news or simply overwhelmed by its steady proliferation, would rather hear from voices associated with something separate from its psychic weight. Figures of respite, like players, are able to translate the closeness and gravity of the virus without the associative anxiety of the news. The NBA understands acutely this direct line to its audience because it has relied on it, albeit as a marketing tool, for years.

This collective, unified voice has stood out where other communication has been fractured. While coming from many different people and their inherent personalities, it has still managed to hit on the notes the national political response is missing. When asked whether that collective tone has helped to deliver a strong, science-based, and compassionate message, Behrens said simply, “That gives us a chance to think about who we are, what we believe, what we care about, [and] to try and communicate that in a way that it shows the compassion and empathy that’s needed as people are unfortunately losing loved ones, are scared, are fearful for their friends and family, are fearful for their livelihood. So making sure that we lead with our heart is important.”

Part of the reason why the NBA’s initial messaging was so ahead of what was being shared by a lagging U.S. government was readily utilizing what had been captured by their colleagues abroad. “We were able to understand from them how some of the cadence of communication would go, what some of those public safety messages were going to be, the social distancing terms that are now a part of our daily lives. It was more trying to get a sense of what was happening there and what the impact was,” Behrens says, but admits there was more they could have taken to heart. “I think even though we were having those conversations, it’s safe to say I don’t think anybody thought it was going to be to the extent we are now living and operating under. So it helped us, but I don’t want to overstate it. There’s still a lot more we could have learned, and are still learning every day.”

That spirit of cooperation has been largely absent from the American federal administration, with information and resource sharing either scarce, rationed along partisan lines, or devolving into infighting when the president’s accountability is questioned. Ego is sabotaging relief efforts and unrelated policies, like attacking immigration, are being used as smoke screens to deflect blame. The NBA is a large, for-profit corporation primarily concerned with entertainment, which can make it seem even more bleak that it is one of the strongest leaders with ostensibly unselfish motives that has emerged in this crisis. Moreover, that it learned from its early lapses and instead of retreating to shed any associations with the virus, appears to have genuinely stepped up to reframe its efforts toward public service.

“This isn’t a program that we developed and put on the shelf,” Behrens says, “I think you asked the question before, did we launch it and keep adding to it, and that’s certainly true. And unfortunately I think it’s something that we’re going to be dealing with for a while. Even though we may move on from this phase, there are going to be additional phases of this pandemic that are going to require more support, more philanthropic support, more community engagement. So we know there’s going to be work to do.”

It should not be up to any private corporation to provide basic, reliable, unified information on public health and safety in a pandemic, nor should people need to rely upon the philanthropic efforts of corporations in lieu of social programs and meaningful financial support in crisis from their elected government. But when the president is making bizarre, dangerous inferences in daily press conferences, justifying his ignorance as a joke while confirmed positive cases in the U.S. surpass one million, this is the reality.

Learning from this seems something that is still far-off, as its tragic fallout is ticking away in present time, but the blueprints that are being established now will be useful to countries not yet as afflicted or in the inevitable future waves of COVID-19 to come. This is as true for healthcare and government infrastructure as it is for entertainment bodies like the NBA.

“In terms of other lessons that we’ve learned, I know we’re all taking notes about things we would like to have done differently, things we could’ve thought about differently but were probably just not ready to tackle that area yet because there’s still so much in front of us that we’ve gotta resolve,” Behrens says. “There’ll be a ton of learnings from here. For everybody. For every country, for every local government, state government, business, you know, what did we learn here so that we can prevent it from happening again.”

The forward motion from here will be in fits and starts. Perhaps the only comforting part of such a global, uncertain future is that it’s shared. No country will proceed smoothly, without regression, disruption, and occasional full-stops. In the U.S., cities, states, and municipalities are still providing different guidelines on lockdown orders, public safety and the future of their economies. “There’s no switch to flip to get everything back at the same time,” Behrens says.

Given there’s no unified plan for states to come out of lockdown and no guidance from the federal government on how or when, the league has another opportunity in front of it. With its announcement that teams may soon start opening facilities in markets where lockdowns are loosening, it will once again be an early COVID-19 model for other businesses, even governments, in what a return to work will look like. If things ease too quickly, then the care the NBA has taken since early March would be made insincere by negligent optics or worse, a resurgence in cases among players or team staff. Teams will need full autonomy to decide whether it is worth the risk or the complicated logistics, and when, at any point, to pull back.

When asked what the next steps are for the league, Behrens gets sidetracked by the difficulties so many communities are facing.

“Healthcare workers, ensuring they have the PPE that they need,” Behrens says. “There’s still such a major issue around food insecurity, especially for kids who are not in school who rely on school meals. For communities that are hard-hit by this pandemic, food insecurity is a big issue. I think the next phase is really going be about the economic issues, and what that means for small businesses and what that means for people whose,” here she stops, pauses for a long beat to catch up and recalibrate, like someone who hasn’t — and really hasn’t — had a break, “livelihoods, have been so impacted.”

Unprecedented has been a word closely associated with the COVID-19 pandemic since its onset, sometimes in the human toll it has taken or its impact on the economy, and one that came up several times in my conversation with Behrens. But there is something striking, immediately arresting, in the way she uses it. “That’s what I meant before too about unprecedented, I think every day we’re learning something new, and in some ways every day we learn less, or know less, about what’s going to happen next.”

It is excruciating to consider that we could be moving backwards, even more to think we are regressing where we’ve already lost so much to learn. But perhaps the most progressive thing, a silver lining we can take even if it has emerged from as unanticipated a source as basketball and its corporate body, is to be honest and compassionate about our failings, and use them as a framework to move forward.