DALLAS — It’s rare to recognize a truly historic Moment — one that ends up earning a capital M — when you’re in it. If you’re lucky, you’ll be able to look back years later and pick out points leading up to what will eventually come to be considered the turning point, the crossroads, the Moment, even though history’s usually told by looking backwards.

Not so for the Women’s Final Four.

Usually, when arriving to a city for the first time to attend an event that it’s hosting, you’ll feel like you’re in a microcosm of one. That microcosm will balloon the closer you get to the event — with sports, it’s usually the closer you get to an arena. Even on a regular game day, being absorbed by a steadily swelling stream of people whose excitement grows, giving way to shouts, chants, and song, is joyful because you’re part of something bigger. In Dallas, site of the NCAA Women’s Final Four weekend, there was no question of what it was the packs of people converging on downtown were there for.

From the day before to the afternoon of the first games, clusters of fans decked out in their team’s gear wandered through the city’s historic district, ducked into restaurants, made the trek to all four team hotels for merch and asked me for directions I very apologetically could not give. At one point, waiting for a light to change, I saw a group representing each of the four teams — Virginia Tech, South Carolina, Iowa, and LSU — at each corner of the intersection, all of them laughing.

The energy was palpable. People were excited, open, and wanted to chat, comparing friendly notes with rival fans on who’d come the furthest to get to North Texas and sharing whooping hopes with people wearing the same colors as them. Events and exhibitions scattered around downtown, like AT&T’s immersive Title IX 50th Anniversary Showcase, featuring past women’s title trophies, vintage uniforms, and a moving cascade of 800+ constantly shifting Getty photographs of women competing in college sports that took over the lobby of AT&T’s Dallas headquarters. Daily panels with guest speakers like Sheryl Swoopes, Arike Ogunbowale, and LaChina Robinson reinforced the excitement and understanding that this wasn’t just a regular weekend of games. This was women’s basketball.

And the basketball was electric. Friday’s double-header was a downhill blur from start to finish. Four plus hours of basketball that was equal parts bracing and agile, sharp and eye-trick smooth. Virginia Tech pulled out ahead of LSU and looked primed to stay there until LSU, in a theme that ran throughout their season and stayed put all weekend, dug into their hybridized blend of all-for-one showmanship. With a five-minute, 15-0 run in the fourth quarter, the Tigers dominated by choking the Hokies’ passing lanes, bullying up for every rebound, and converting nearly every stop they got.

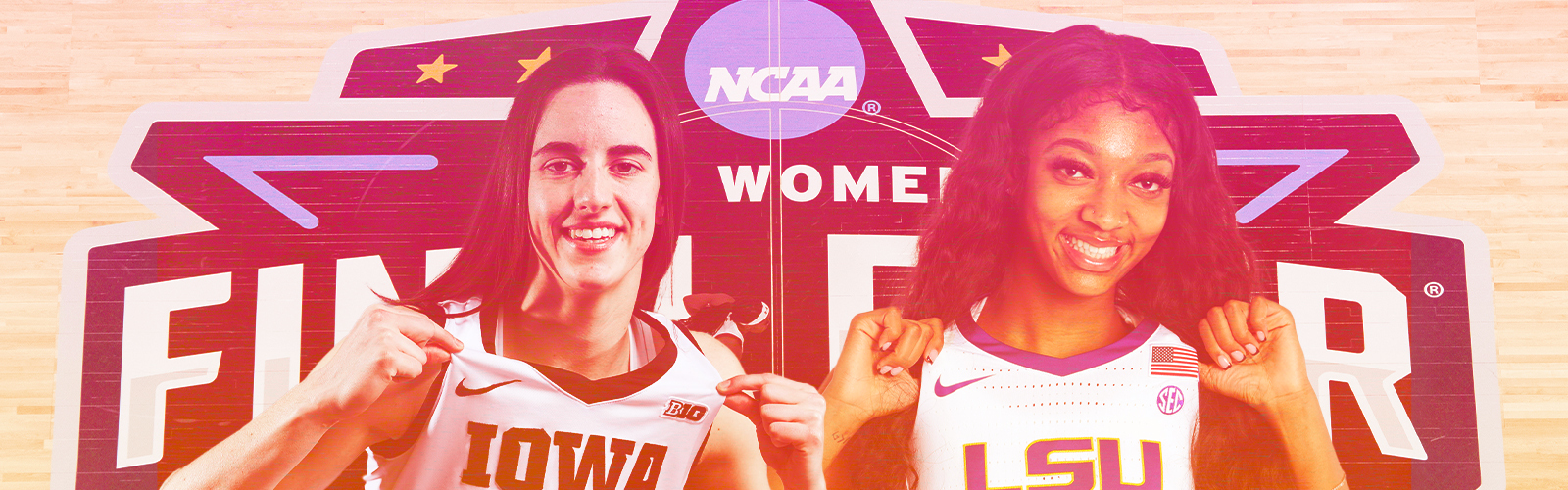

In the second match up of the semi-finals, the tournament’s underdog, Iowa, ran onto the floor to arena-shaking cheers against the South Carolina Gamecocks. Coming into the game 36-0, Dawn Staley’s group was as cool as their record reflected, refusing to get rattled by Caitlin Clark turning it on early and often. Even with their composure and staggering advantage on the glass, South Carolina 42-game winning streak was overrun by Clark’s 41-point, record-breaking game.

(A brief aside: Watching Clark, it has to be said even if you’ve already heard it, conjures up a rare, out-of-body basketball watching experience. When she pulls up from deep, she doesn’t line up, doesn’t wait, barely straightens up — just shoots. Automatic as breathing.)

Going into Sunday, even after a Saweetie show Saturday night that featured a gleeful appearance from LSU’s Angel Reese, the mood in Dallas was quiet, tamped down. The block party buzz of Friday evaporated with the rolling thunderstorms through the city, and even in the arena, while fans were alert and the air was charged, LSU and Iowa took to the floor dutifully zeroed in.

Where the Hawkeyes came out intent on getting Clark down the floor to shoot, the Tigers were balanced. For a group that added nine new players this year, the fact of their working out together in summer before their school year started was clear. LSU played an intuitive, connected game of disruption and intensity. Even against heavy-handed calls by the refs on both teams, LSU saw vital contributions from their entire roster and were up 17 by the half.

When Iowa worked hard to get their offensive legs under them, the Tigers tripped them up or outright kicked them out. For how much LSU operates on a technical string on the floor, that same tether ran through the group like a conduit for joy. Watching senior guard Jasmine Carson score 22 points came from the cumulative work it takes to be ready to step in the moment, but when she did, her teammates lit her up. It’s one thing to watch a great team play well. It’s totally another to watch a great team play well and have a ball doing it. It’s also a near impossible combination to beat.

The gravity of the win, once the confetti cannons finally ran out of paper fuel and every player on LSU’s roster cut down their piece of the net, was clear in the Tigers postgame. Already there had been online chatter building about Reese, pointing at her ring finger and waving a hand in front of her face while trailing Clark around the floor as the clock ticked down. The one-sided pearl-clutching of “celebrating the right way” while the loaded duality of being a woman, and a young Black woman, further fuelled calls that Reese was behaving in a way that was “classless,” like Clark hadn’t done the same a week earlier, and like removing that fact from the discussion wasn’t weirdly infantilizing her. Clark has since called the discrepancy out.

“All year I was critiqued about who I was. I don’t fit the narrative. I don’t fit in the box that you all want me to be in. I’m too hood, I’m too ghetto. Y’all told me that all year. But when other people do it, y’all don’t say nothing. So this is for the girls that look like me,” Reese said facing the media. “This was bigger than me tonight.”

And it was. In the way that Reese meant it, for young Black girls watching (according to an email from WSN, searches for girls basketball clubs spiked by 305 percent in the U.S. and 236 percent worldwide following the game), and for the record 9.9 million viewers watching the Women’s National Championship game across ABC and ESPN2. As of March 14, all ad inventory for women’s tournament had sold out and preemptive spots for pregame shows ahead of the Final Four went with them.

There’s a prediction that the women’s tournament could be worth $112 million by 2025, a very lucrative boost as there are calls from some of the most prominent names in the sport for the NCAA to pursue a separate television deal for the women’s and men’s tournaments. It’s a stark contrast to the 2021 women’s tournament which came under fire, enough that the NCAA was pressured into commissioning an external review of the organization’s historic treatment of the women’s game, when viral videos shot by athletes like Sedona Prince showed a sharp difference in amenities, lodging, and equipment to the men’s tournament.

The report found “systemic gender inequity issues” and the perpetual undervaluing of women’s teams by reinforcing “a mistaken narrative that women’s basketball is destined to be a ‘money loser’ year after year.” Given the report, and the lucrative numbers by broadcast and revenue standard generated in Dallas, the old, exhausted adage that the women’s game isn’t good for business falls flat, and overdue, on its face.

It’s also why this past tournament wasn’t, as can happen when brands work fast to atone, an over-correction. You soon realize when dropped into the thick of something like the Women’s Final Four weekend that there are no women’s basketball generalists. Fans are adroitly dialled in, with an awareness that branches beyond the bounds of their own allegiances, making the average “baseline” of knowledge huge. Arguably, yes, the so-called “generalists” that travelled to Dallas for the weekend shouldn’t really be called that, because even with no team in the running, these fans felt determined enough to make the trip. Still, a part of me wants to believe that these types of diehards do represent the average women’s basketball fan, because when you’ve historically had to work twice as hard to find coverage, even to watch live broadcasted games to have a sense of being proximal to the action, it’s going to deeply personalize your interest.

The goal, as the women’s game palpably grows, as future attendance records are shattered like they were in Dallas, isn’t to lose that level of intensity in fandom. It is to gain casual fans, fair-weather fans, just happy to be here fans, alongside the rabid ones. To have generalists. As Clark said to Jeremy Schaap of Outside the Lines following the tournament, “the viewership speaks for itself.”

The women’s game will always be exceptional, the goal is to grow it away from being treated as anomaly; as something either too niche to explode in the public consciousness or too specific and rare to survive on its own sure, skilled feet. The goal, well underway, is really pretty simple. Give women’s college basketball a platform that gets it to tens of millions of screens, and step back to let it cook.

Dime was invited on a hosted trip to the Final Four through AT&T for reporting on this piece. However, AT&T did not review or approve this story in any way. You can find out more about our policy on press trips/hostings here.