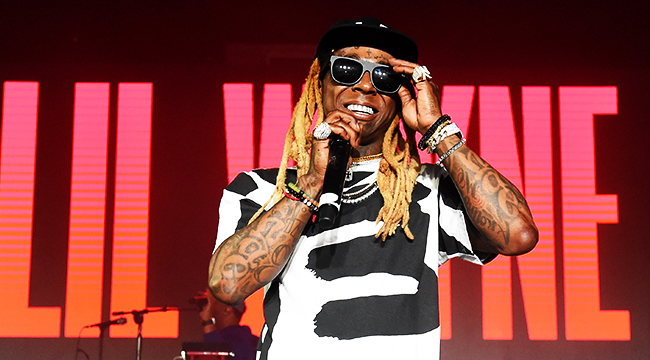

Lil Wayne closed out 2017 with a bang. After previously releasing a slew of freestyles throughout December, he dropped Dedication 6 on Christmas, a much-appreciated gift for his fans. Still beleaguered by label woes which are holding up his long-awaited Carter 5 album, Wayne didn’t bother throwing potential singles at the wall, he went back to the freestyle format that first ascended him into rap superstardom — and showed that he still has it. It’s fitting that with the dozens of freestyles on the project (and more to come), Lil Wayne, a champion of wordplay, was able to achieve a dual purpose. Not only did he re-affirm his status as the forefather of this hip-hop generation, he also placed another bid for king of the freestyle.

Before we continue, let’s be clear: I’m not saying Wayne is a pro at improvisational, off-the-top rhymes, I’m referring to the freestyle in the sense of what Big Daddy Kane deemed a written rhyme “free of style” or concept. I’m talking about a two-to-three-minute exhibition of your raw lyrical ability, wit, and mastery of flow. With projects like Da Drought series — specifically Drought 3 — Wayne is perhaps the lone southern artist who stood toe to toe with fellow kings of the freestyle format like Jadakiss, Cassidy, Lloyd Banks, Fabolous, Juelz Santana and others.

Many may know Gillie Da Kid primarily as “the guy that accused Wayne of ghostwriting,” but he has his own legacy as a member of Philly-based group Major Figgas — who were allegedly Rocafella’s first choice for a Philly group before State Property. When Gillie signed to Cash Money, it’s obvious that he influenced Wayne, whose delivery went from a simpler flow more reminiscent of Cash Money comrades B.G. and Birdman to a more intricate technical approach on songs like “B.M. Jr.” Gillie left Cash Money in 2003, then began throwing the ghostwriting rumors on rap DVDs in the mid-‘00s. Regardless of how involved Gillie was in Wayne’s rhymes, it’s telling that Wayne got even better after Gillie fell out with the label.

By then, Wayne already had the technical rhyme ability, and his skills were further sharpened when he started running with Juelz Santana, who was a burgeoning star with Dipset, in the early ‘00s. In 2005, Wayne dropped The Carter 2, on which his knack for memorable wordplay such as “Coke transactions on the phone we call it ‘blow jobs’” really started to shine. Being around witty MCs like Juelz Santana, Cam’ron, and even JR Writer and Hell Rell no doubt influenced his craft. Dipset is known for deeply assonant rhymes and amusing, rewind-worthy one-liners. Being in that mix helped Wayne soak up those attributes, which we started to hear on projects like Dedication 2 and the Drought series.

https://youtu.be/sz9kAsAb3VQ

You can also credit Wayne being around a raw lyricist like Currensy who no doubt sharpened his sword. You can applaud the decision to stop writing rhymes, which influenced his delivery. You can note his competitive fire to outdo Jay-Z — that’s still at play on tracks like his “Family Feud” freestyle. Even Birdman deserves credit for letting Wayne explore his creativity with a hands-off policy — possibly because he was too busy rubbing them together while thinking of luxury cars to buy.

By the end of the aughts, Wayne became a Billboard mainstay, which means his efforts went more into songs than freestyles. Since running into legal issues with Birdman and Universal Records though, he’s released well-regarded projects such as the Free Weezy Album and No Ceilings 2. With 2015’s No Ceilings 2, he did his thing on 25 of the year’s hottest beats, showcasing that he was still capable of being on top if he had the freedom to release studio albums. He recently doubled down with Dedication 6, a project that’s a scintillating reminder of who he is.

What’s impressive about Wayne’s freestyle catalog is that it’s so brilliant despite him not veering far from just three topics: his sexual prowess, his guns, and his bank account. Most freestyle-heavy artists are pretty redundant, but where he sets himself apart from rappers who ended up languishing in the freestyle format though is that he’s gifted enough to weave his witticisms into a constantly changing flow — instead of the other way around. Whereas artists like Cassidy and others fixate on one standard cadence which makes them sound redundant and creates awkward throwaway lines crammed in just to rhyme with their punchline, Wayne lets each beat dictate his flow, then stacks up imaginative lines within that flow like he did on “Bank Account”, “Fly Away,” “Eureka,” and so many other D6 tracks.

No doubt, Wayne has his head-scratching lines that inevitably fall flat, but that’s to be expected. It’s like being a shot blocker in basketball: When you jump up to defend every dunk, you’ll inevitably make a fool of yourself a couple times. But Wayne had it together for the bulk of the tape, showing he’s a modern-day rap sensei. He’s as invigorating as a Young Thug or Future but actually says more, and he’s as witty as a Fabolous but delivers his rhymes in a more dazzling fashion. That untamed flow is what makes the punchline palatable for hit songs and future listens way down the road. He’s also more lyrically inclined than he’s given credit for. Somewhat like a Biggie or Jay-Z, Wayne bunches “simple” vocabulary together in intricate, prolonged rhyme schemes to the point where his lyrical dexterity has to be respected.

https://youtu.be/RSKAXl5AQM0

Even if his subject range is limited, his toolbox is anything but — which is why you hear his influence in rappers like Kendrick Lamar all the way to turn-up champs like Young Thug. It’s why artists like Kendrick and Chance The Rapper and trap stars like Ralo and Thugger call him a G.O.A.T. Wayne influenced a wide amalgamation of MCs because his own influences were vast.

The freestyle mixtape legacy that he carries on was popularized by figures like DJ Clue and DJ Kay Slay in the late ‘90s. You could literally spend hours on YouTube going through old Lox, Desert Storm, Dipset and G-Unit freestyles — and that’s not even counting rappers from Philadelphia like Beanie Sigel, Cassidy, Reed Dollaz, Cyssero and more. Philly and New York are probably the two ruling kingdoms of the freestyle format — and Wayne happened to have ties to both cities.

It’s those relationships and circumstances that shape the idea that the king of the freestyle mixtape format may not even be from the tri-state area or Philly, but way down bottom in the boot. With each tape full of hilarious, grimace-inducing, melodic streams of consciousness, Wayne cements his greatness. As much as traditionalists pin hip-hop’s perceived downfall to him, it’s worth noting that despite being veritably locked out of his own kingdom by virtue of label woes, he hasn’t taken his ball and gone home like he wanted to last year. He’s resolved to rap his ass off, stacking bars high enough to stand atop his pedestal and get his acclaim while he’s still here. That’s dedication.