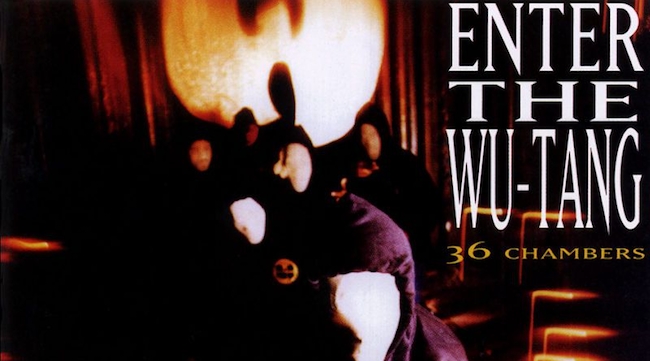

Friday marks the 25th anniversary of Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter The 36 Chambers, a sword-slashing, ominous epic that carved a left-field path for every hip-hop iconoclast to follow. The album’s one of a kind conception, and the ascendance that followed it exemplifies the power of hip-hop’s early-to-mid-1990s Golden Era. People don’t swear by ‘90s hip-hop as a mere nostalgic talking point. Their love for the Golden Era can be explained through the tremendous impact of the Wu.

In the early ‘90s, hip-hop music was defined in part by Dr. Dre’s G-Funk sound, the Teddy Riley-popularized New Jack Swing, and the feel-good stylings of Native Tongues collective acts such as De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest. The Wu’s breakout single, “Protect Ya Neck,” was the antithesis of those polished soundscapes, as was the rest of 36 Chambers.

The album, which was entirely produced by RZA, was as frenetic as New Jack Swing and informed by the sample layering techniques of RZA’s peers Prince Paul and Q-Tip, but for the most part, he concocted his own sinister formula at Staten Island’s Firehouse Studios. 36 Chambers eschewed radio-friendly mixing for a murky soundscape of quaking, dusty kick drums and piercing snares serving as the foundation for a rollercoaster ride of menacing basslines, gloomy jazz and soul loops, and of course, those classic, song-anchoring vocal clips from Kung Fu flicks.

The Kung Fu samples weren’t gimmickry. They were a cue to let the listener know they were listening in on a fight on each record. True to Dr. Dre’s formula with N.W.A, RZA had assembled a supergroup of the best MCs in New York’s forgotten Staten Island borough and let them tear his beats to pieces each night in the studio. Each artist had their own flair that made them a unique asset to the Wu-Tang chessboard.

There was the mastery of flow and mass appeal that Method Man delivered, the cerebral eloquence of GZA, the free-associative narratives of Ghost and Raekwon, and ODB, the ultimate wild card in hip-hop history. Inspectah Deck is one of the most underrated rhymers in rap history, and U-God and Masta Killa both had scene-stealing moments throughout the Wu-Tang catalog. RZA asked each man, who was either fledgling in the industry like him or in the streets, to give him a year of their life to craft 36 Chambers. The rest was history.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSeLeQue7I8

A primary reason hip-hop heads obsess over the ’90s is because of the sheer amount of talent roaming New York alone at the time. The Wu is exhibit A. It’s damn near divine how RZA was able to round up not just his cousins GZA and ODB, but a slew of MCs who would become full-fledged rap stars in their own right. These days the Wu’s collection of talent is rare to find in an entire city, much less in one section of a city.

When people bemoan the state of modern mainstream rap, it’s often unsaid that maybe we were just spoiled by acts like the Wu. It’s very likely that we’ll never see a nine-man coalition of imaginative, talented, charismatic rappers that powerful again. There will never be another rapper like Ghostface Killah or Raekwon The Chef. You can’t say that about many MCs. It’s why I’ve always treasured ’90s music instead of feeling an arbitrary need to “move on” or retrospectively kill the sacred cows as modern rap writers love to do. Time doesn’t exist, but Wu-Tang is forever.

RZA spearheaded their movement masterfully. After having modest industry success, he went back to the drawing board as a producer and set out to develop his own sound. He wasn’t interested in mimicking what worked for Tribe or Big Daddy Kane, he explored his own mastery of his beat machines. He figured out how to fully maestro, from ordering each artist’s vocals a certain way to making special breaks in Method Man’s part of the beat in order to bolster Meth’s already dynamic flow.

That kind of production ingenuity is what made 90s rap production so brilliant. For the best producers, it wasn’t enough to merely loop a sample. The sample had to be pitched, chopped, then mixed-and-matched with other samples in a thrilling sonic gumbo. 36 Chambers was composed of RZA experimenting and refining the blueprint that would mark him as a production stalwart for over a decade.

RZA and the Wu were rewarded for their bold sound, but it wasn’t an overnight thing. Even in the ’90s, 36 Chambers’ dusty sound was an acquired taste — but millions of fans came to love it. In today’s streaming market, an act releasing avant-garde music like the Wu can sidestep traditional media/radio platforms and achieve respectable notoriety, but there was a point for years where that wasn’t easily the case. In the late 90s and 2000s, homogenized radio playlists began to stifle the variety of mainstream hip-hop.

Almost any act whose sound was considered inaccessible became relegated to the underground, which undermined the dynamism of hip-hop that made people love it in the ’90s. Today’s ten-song radio blocks dominated by syrupy singles and telegraphed “for the ladies” records make you appreciate the fact that an uncompromising, coarsely-mixed song like “Protect Ya Neck” could be a breakthrough single just off the strength that it was good and radio program directors believed in it.

It’s anomalies like “Protect Ya Neck” that build the lore of the ’90s as an unregulated, wild west of a scene where anything went — and anything could happen. In today’s wired world we know everything the moment it occurs — and it’s shoved down our throats — but mystery around an act can bolster an air of intrigue that’s at the bedrock of fandom. The Wu has their share of lore. Whether it’s stories about ODB’s infamous antics or the rumor that record labels implored their acts to never mention the Wu-Tang Clan by name, some aspects of the Clan’s legacy carry on by word of mouth only.

For instance, what exactly was lost during the floods in RZA’s basement studio? RZA says he lost over 300 beats. Raekwon has said it was closer to 500. Inspectah Deck said his Uncontrolled Substance album, set to roll out along with the initial Wu solo classics in the mid-90s, was lost in the flood and was “a totally different album” then what was ultimately released. Raekwon said they lost beats that were “a collage of organic violins and certain eerie sounds… knockers and bangers and beats that was challenging to us” from the likes of RZA, Wu Affiliate producers and even ODB.

Who knows how much deeper entrenched the Wu’s legacy would be with even more universally regarded classics in their canon? Regardless, it’s already set in stone with 36 Chambers as the linchpin. 25 years ago they urged us to enter the chambers, and through dozens of solo albums and influence on the whole of hip-hop, we’ve never left. Their music defined a period that is often defended as obnoxiously as RZA’s drums banged perfectly. While nostalgic fans can be annoying, just understand that they’re celebrating greatness. And that fact is nothin’ to f*ck with.