The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted practically everything, and that certainly includes the music industry: tours have been postponed or canceled altogether, releases have been pushed back, and musicians the world over have been forced to consider different approaches when it comes to almost every aspect of their profession. But for Gus Dapperton life in quarantine times has been — as much as it can be — business as usual.

“There was no drastic change for me,” the 23-year-old musician born Brendan Patrick Rice states as we spoke over the phone last month. He’s dialed in from his Brooklyn apartment, where he’s been holed up since deciding to take a break from the constant touring grind at the top 2020. “I’m pretty used to being at home in my apartment and home studio, messing around. So I’ve just been taking it all in, observing, learning, and not forcing myself too hard to be creative.”

During this period of relative downtime, Dapperton put the finishing touches on his sophomore album Orca (out September 18), a record of overcast, glowing pop-rock that he largely wrote while on the road promoting his breakout debut, last year’s Where Polly People Go to Read. “I had a lot of music done already, so I wasn’t pushing myself too hard to finish things,” he reflects on the necessity of going easy on himself over the past six months, while emphasizing the restorative effects of solitude on his mental well-being. “I was introverted when I was younger, and I still am. I’m able to spend long periods of time by myself, so it’s been a good change of pace for me instead of touring and meeting so many new people every day.”

There’s a sense of relief palpable in Dapperton’s voice as he finishes that last sentence, and with good reason. Since his music started receiving attention online in 2017 — a streak of internet-native success that led to his current record deal with indie-focused label AWAL, as well as placement on the soundtrack for the second season of Netflix’s teen drama 13 Reasons Why — the resulting success, as he tells it, has proved overwhelming.

His story so far is as unique to his own experiences as it is increasingly common in popular music: a young bedroom-bound auteur builds an audience online, the music industry takes notice, and before long things are moving so quickly that it becomes difficult to keep one’s feet on the ground. But despite being a denizen of the digital era, Dapperton professes an overall lack of online engagement, claiming that he mostly uses social media “more to observe” than to directly interact with others. He’s similarly quick to downplay the notion of himself as an artist borne out of logging on — more than reasonable, really, when considering his IRL artistic beginnings.

Dapperton grew up in the upstate New York town of Warwick, with early memories of “Friday night dance parties” in which his father hooked up a Hi8 camcorder to their television so the whole family could see themselves grooving on TV. While dodging the ever-present pressure to participate in his town’s athletics programs, Dapperton spent his adolescence skateboarding and engaging in minor creative pursuits with friends that he lovingly refers to as “outcasts.”

With little in the way of formal training or lessons, Dapperton was bitten by the musical bug in eighth grade after his music teacher issued an assignment that doubled as a contest: He and his fellow students had to write, produce, and record their own song using Garageband, and the winners would get to play their music on a local radio station. Dapperton won off a song called “Shock,” his sister Amadelle possessing the only copy of which to this day; the early taste of success left him wanting more. “I was like, ‘Wow. I want to do this for the rest of my life,'” he recalls.

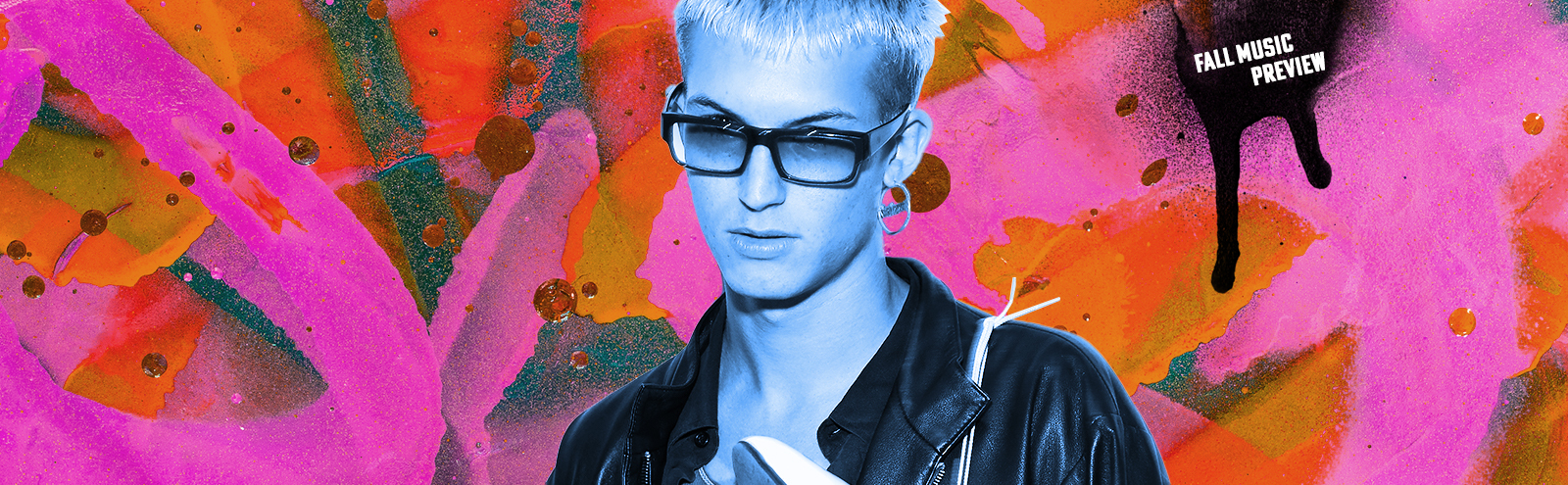

Citing early influences ranging from legendary hip-hop producer Madlib to Taylor Swift’s self-titled debut, Dapperton initially dabbled in production before pivoting to full-on songwriting “once I found my voice and decided I had a lot I wanted to say.” His off-kilter, distinctive fashion sense — a style highlighted by Dapperton’s taste-the-rainbow predilection for hair dye, including the cherry-red hue he sports on the cover of Orca — emerged around this time too, as he dug through thrift stores and artfully distressed his duds.

If Dapperton’s parents were accepting of his constantly changing appearance, they possessed a bit more apprehension when it came to his pursuing music as a career. “They thought the extent of a musician’s career was a jam band playing at a restaurant,” he chuckles; eventually, they came around after his father’s perspective was shifted by Malcolm Gladwell’s 2008 book Outliers: The Story Of Success. “I think he read that and thought, ‘Well, I guess my kid puts more hours into this than I’ve seen any other kid put into anything.'”

In 2014, Brendan Patrick Rice officially became Gus Dapperton after uploading the laid-back, hip-hop-flavored “If the Sky Was Vivid,” featuring his friends Elijah Bank$y and Lo.Rd Lingo, to one of his multiple Soundcloud accounts he maintained “back when it was less for listening and more for creators.” “It was the same as naming a newborn baby,” he explains when asked about the origins of the Gus Dapperton moniker. “I heard my voice had this sound, and I thought the name summed up the sound, as well as the person that I wanted to be — someone who wasn’t afraid to express themself and create.”

The song turned Dapperton into an overnight internet sensation, with a string of buzz-building EPs — Yellow And Such in 2017, the following year’s You Think You’re a Comic! — that followed as he, while finishing high school and attending Drexel to study music technology, became a self-described “worse student.” After two years at college, he made the decision to drop out permanently to focus on music full-time: “It wasn’t a super encouraging program. I learned some of the equipment, but I just couldn’t focus. After two years, I just couldn’t do it anymore.”

Dapperton hesitates to describe the three years that followed as a “blur,” but the rigors of near-constant touring — which carried through the creation and release of Where Polly People Go To Read, the title of which referencing a fictional people that Dapperton drew as a kid — undoubtedly wore on him. “As soon as I started touring, the last three years of my life went by so fast,” he recalls. “I was making and recording music on my tour bus, and in hotel rooms — writing songs whenever I could. I’d be living with someone for three months, and then I’d be across the world playing shows.”

It was under this strain that Orca came together, the dusky first single “First Aid” one of the first songs he wrote for the project. “It’s about these deeper and darker thoughts I’d neglected to be a strong person — but in reality, being a strong person is about confronting those feelings,” he explains while discussing the song’s thematic bent, elaborating that its lyrical intentions also encompass Orca as a whole. “When I’m feeling depressed and lost in the world, there’s not many things that help me. Therapy doesn’t help me very much. But putting it into the music is very therapeutic for me.”

Orca is a melancholic departure from Dapperton’s vibe-oriented earlier material; his raw voice is surrounded by full-bodied instrumentation that as much recalls Death Cab For Cutie as it does generational scions like Mac DeMarco and Porches. It bears the overall mark of someone pushed to the brink of excess that overnight success in the music industry is often accompanied by — a careful retreat, with no short supply of personal reflection and self-care. “I’ve probably missed out on a lot of the life lessons that people go through in adulthood, so there’s this huge imbalance in my life that I’m reflecting on,” he explains. “The longest break I had over the course of three years was a month. I’d have to socialize while playing this music that I consider very sacred to myself every night. All of that on top of not getting eight hours of sleep, having physical exhaustion, drinking every night — it takes a huge toll on you.”

Dapperton describes Orca as an album about “feeling trapped, depressed, and having these people and unconditional forces of love in your life that reel you back in.” It’s fitting, then, that Amadelle joins him throughout the album as a vocalist, providing literal harmony to his fractured feelings. The pair have collaborated in some form since early adolescence, but Orca represents their artistic kinship more than ever before — an embodiment of Dapperton’s message that the ones you love are the ones you need the most. “A lot of the things I’m talking about are really timely right now,” he states on what the future might hold for him, choosing instead to reflect on the potential impact his music could have during our peculiar societal moment. “I have a responsibility to release this music.”

Orca is out September 18 via AWAL. Get it here.