The climate changes at least three times in the drive from San Francisco into Tomales Bay just north of the city, and not subtly so. When I made the trip at the beginning of July, San Francisco’s famously foggy microclimate, barely hitting 60 and feeling much colder with a wet mist blotting out the sun, remained with us past the city and all along the grand red towers of the Golden Gate Bridge. Still shrouded in misty grey funk when we hit the south entrance of the Robin Williams tunnel (the tunnel’s entrances painted in rainbow, like Mork’s suspenders), the sun came out at some indeterminable point between entrance and exit, squirting us out into a bright sunny summer day almost like a switch had flipped.

The sun stayed with us all through east Marin County, further inland and on the bay side, where the 101 winds past Sausalito’s houseboats (which aren’t really “boats” at all, so much as floating houses on a pier, built by artist squatters after WWII) and up through Marin’s million dollar real estate in Mill Valley, Tiburon, and Strawberry, where houses with tall windows have brilliant views of the bay from secluded hillsides, where their owners spend the weekends clad in biking spandex, hollering at motorists to share the road.

Our destination was across the strip of rugged, hilly land separating bay from breakers, all the way over in rural west Marin, as distinct from tony east Marin culturally as it is meteorologically. East Marin’s sunny warmth, in the high 80s that day, lasted until about the last 15 minutes, when, abruptly once again, the air turned cool and the landscape went from dried yellow weeds (the gold in “The Golden State” and “The Golden Gate Bridge”) to verdant green moss. You lose cell service around the same time.

Even in a state as geographically diverse as California, Tomales Bay stands out as its own esoteric little pocket. Cows graze in fields and moss hangs from trees, a fecund patch in the heart of the otherwise dry far West. One of the other van passengers noted “it looks like a French fishing village.”

We’d all accepted an invite from Humboldt Distilling to come sample their wares with ideal pairings and situations at Hog Island Oyster Company in Marshall, California, right on the shoals of the aforementioned Tomales Bay. The hot topic on the ride over was “merroir.” It’s an industry-invented term, meant to explain why oysters, which almost always come from just a few different species, spawned in about 10 hatcheries serving all of North America, can still taste so distinct from each other.

The answer is that the oysters tend to take on the characteristics of the sea where they were farmed (and the vast majority of the oysters consumed in the world come from farms, only a tiny fraction are wild collected). Those sea conditions tend to vary wildly, from the muddy, shallow bays of the mid-Atlantic to Tomales Bay’s frigid waters, frequently replenished by Pacific “upwelling,” a process by which high winds off shore dredge up waters from the depths.

That cold water Tomales Bay oyster grow in is more sea than shore, and the abundance of cold, deep ocean water gives Hog Island’s oysters a briny, salty, fresh character (as well as an interesting cucumber note). Wine, of course, has long been considered the finest expression of the combination of the geographical, geological, agricultural, and climatic conditions that produced its grapes, such that anyone with a decent palate can tell whether the wine came from limestone-rich or volcanic soil. Which gives the wine a “sense of place — for which the French coined the term “terroir,” as the French are wont to do (see also: “mise en scene” for movies).

Oysters, of course, have much the same thing, a combination of all the particular local conditions that produced them. Only, they come from the sea — mer — rather than the ter of “terroir.” Ergo… “merroir.” It’s a perfectly cromulent word!

We were welcomed to the foggy shores of Tomales Bay (one of three California bays healthy enough to support large-scale oyster production, along with Humboldt and Morro) with an oyster shooter — basically, a double shot-sized Bloody Mary served with a Hog Island Sweetwater oyster on top — mixed up by Hog Island’s beverage director, Saul Ranella.

It may not shock you to learn that a cocktail prepared by a beverage director, specifically to highlight a liquor, made to pair with an oyster just pulled from the water of that oyster farm, and eaten in view of its habitat, was extremely good. This oyster shooter was like a further, brinier-but-wildly-fresh version of a Caesar — the Bloody Mary‘s Clamato-based cousin, which my in-laws converted me to a while back (it’s not as thick as a Bloody Mary and clear liquors pair weirdly well with seafood brine).

[Ranella’s shooter ingredients: Humboldt Organic Vodka, Kummel, Hog Island Bloody Mary mix, lime, and Tapatio hot sauce.]

After that, we took a tour of Hog Island’s oyster farm, founded in 1983 by three marine biologists. Oyster farms aren’t the most terribly interesting places, seeing as how oysters tend to lead a sedentary lifestyle ensconced in their own shells, mostly sitting out in their baskets, eating food and waiting to fatten up enough to be plucked out and eaten (much like your mother). But whatever bivalves may lack in action photography potential they more than makeup for in sustainability.

In an age when it’s hard to consume any seafood guilt-free (or virtually anything, for that matter), oysters are surprisingly green. Not only are they not overfished, like so much wild-caught product, the farms that produce them actually help clean the waterways where they’re grown rather than pollute them. This thanks to oysters’ filter-feeding capabilities. Of course, it takes clean waterways to produce consumable oysters in the first place, and dozens of entities are testing the chemistry of Tomales Bay’s waters at any given time to ensure their viability for food production.

Clean water, of course, is key to both making Humboldt Vodka and farming Hog Island Oysters. Which was presumably the basis of their partnership on the day. The distillery had recently announced their “Toast To The Coast” campaign, pledging to donate a portion of their sales to the California Coastkeepers Alliance (CCKA), a non-profit dedicated to fighting for clean waterways in the state.

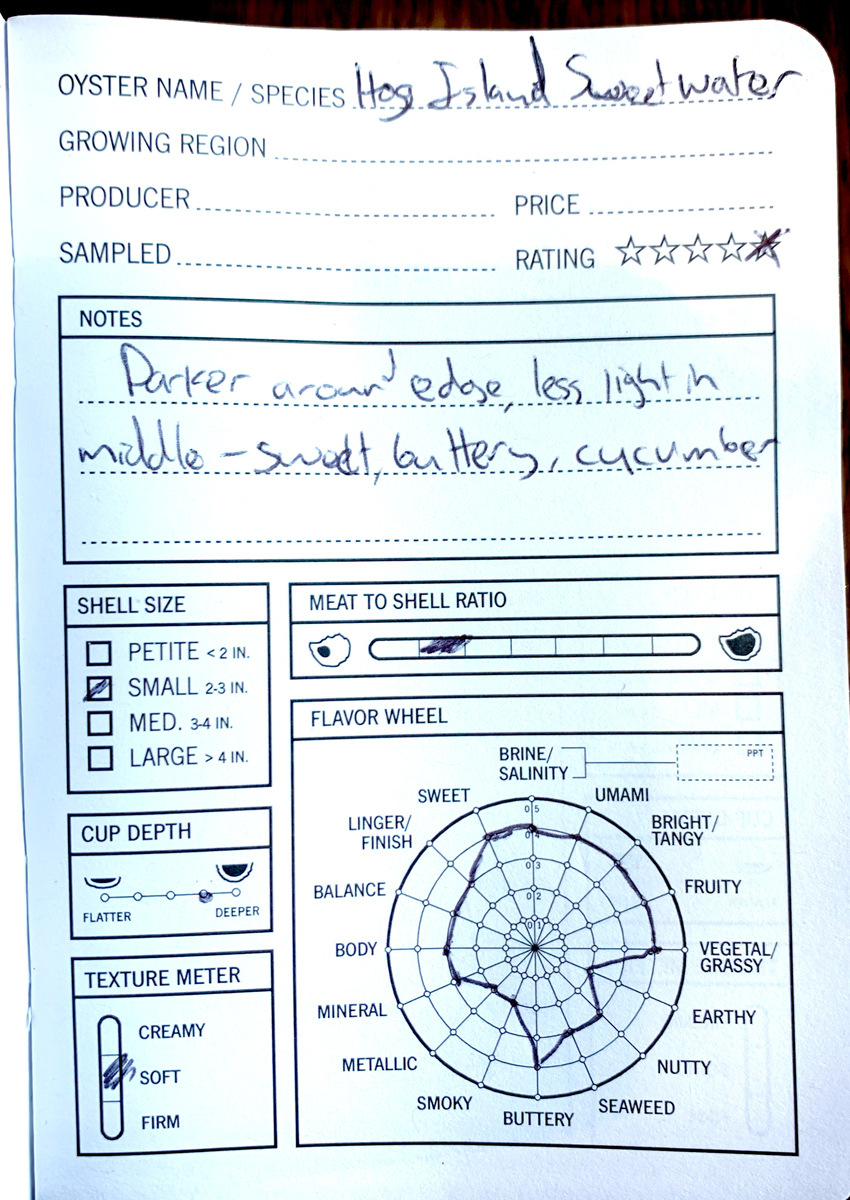

More tastings followed, along with some shucking, led by “international oyster sommelier” Julie Qiu, who almost certainly knows more about oysters than you. As we tasted through Hog Island Kumamotos (Crassostrea sikamea), Hog Island Atlantic (Crassostrea virginica), and Hog Island Sweetwaters (Crassostrea gigas), Qiu regaled with oyster facts and handed out her self-designed oyster-tasting notebooks. Which included an incredibly thorough “flavor wheel” ranking the oysters on 16 different characteristics: Brine, umami, bright, fruity, vegetal, earthy, nutty, seaweed, buttery, smoky, metallic, mineral, body, balance, linger, and sweet. Phew.

If I’m honest, I’m not exactly thrilled at the idea of trying to take extensive, clinical notes while I’m trying to enjoy an oyster. But it speaks to one of the things I appreciate most about oysters: the ritual. Any former drug addict will tell you, that part of the addiction is the ritual it requires. Bring out your little bag of tools, tie off the vein, cook the powder in the little spoon, suck the liquid into the syringe… We humans find solace, maybe ascribe meaning, to these little collections of repeated action (every religion involves ritual, some are only ritual).

While I’ve thankfully never shot heroin, I find myself being drawn over and over to the same kinds of things in my own life, whether it’s espresso (grind the beans, tamp the grinds, clean the steam wand, steam the milk, pull the espresso, pour the milk…), avocado toast, or hell, probably golf (see the hole, remember the hole, practice the swing, deep breath, waggle-waggle…). It’s the dream of doing something over and over, getting it just a little closer to perfect each time. Some perfectionists do drugs; for some perfectionists, perfectionism is the drug.

Oysters lend themselves easily to this kind of ritualism. The way you carefully insert the shucking knife into the hinge, apply pressure until it releases, then move the knife gently from side to side to create space, separate the roof of the shell from the meat, and then the meat from the bottom by severing the abductor muscle (fun fact: French restaurants don’t sever the abductor muscle when shucking, which kills the oyster, preferring to leave it attached so that it’s alive right up until the moment you eat it — which makes a kind of sense, but also sounds like a pain in the ass when you’re trying to slurp one). Then you carefully remove the lid, make sure not to spill any little shell bits into the shucked oyster; add your mignonette, lemon, hot sauce, horseradish, whatever; and slurp it down. It’s all wonderfully ritualistic. I’m convinced oysters taste better because of the ritual they require.

For most of my oyster-eating life, even the act of getting them was part of the ritual. It was so hard to spend $3-4 per oyster when you could drive an hour and get them in bags of 50 or 60 for 50 or 75 cents per (sadly they’re more expensive than that now). Plus, you’d miss out on the experience.

Having since moved inland to Fresno (which is still pretty close to the sea relative to the rest of the country, but feels like another world from coastal California) I have yet to consume an oyster in the city where I live. In 2020, I took my wife to Tomales Bay for oysters and my friend who was supposed to join us stood us up. Thus leaving me with 70 or so oysters and a wife who, as it turned out, doesn’t enjoy oysters quite as much as I do. It took me two or three days, but I ate most of them. There’s a strange thing that happens when I eat oysters: they make me happy but not full. I can enjoy them in almost unlimited quantities and still eat a regular-sized meal directly afterward. I’ve never felt bloated or sleepy after eating one.

I learned plenty from Qiu, but if there was one thing I retained, it’s that maybe I’ve been too precious in my oyster consumption. Yes, you can get food poisoning from eating raw oysters, just as you can from eating damned near anything. But Qiu estimates that she’s eaten upwards of 7,000 oysters in her lifetime (and she seems detail-oriented enough that I’m inclined to believe her) and has never gotten sick, not even once. Considering oysters are bivalves, whose entire physiology is designed to be able to close up and survive inside their own “house” (so to speak) when the tide goes out and with it the water they need to survive, and that they’re literally alive right up until the moment you shuck them, they’re actually pretty safe.

Any FDA-regulated oyster farm has its water tested constantly and is highly regulated. As long you’re getting oysters that have been kept refrigerated (below 40 degrees Fahrenheit) and are still alive when you shuck them (the shell should be closed or should close when you tap on it) there’s relatively little to worry about. The whole “don’t eat oysters in months that end in R” adage, while weirdly pervasive, is outdated in the age of oyster farms and refrigeration. Basically, if it’s dead, stinky, or looks dry* (ie, not plump, juicy, and glistening**) when you open it, don’t eat it.

I still remember what a professional fish grader at an ahi auction in Hawai’i told me when I asked him how one grades fish: “You were built for this,” he said. “You have an intuitive sense of what makes meat look healthy and inviting. Trust those instincts.”

I’ve applied that rule of thumb every single time I’ve bought any kind of meat since, and the same thing seems to apply to raw oysters. If it looks vibrant, plump, and fresh, it’s most likely because it is. If it looks, smells, or tastes weird, don’t eat it, or stop eating it. Qiu also keeps an updated list on her website of farms that will ship direct to consumers, in case you don’t trust that your local supermarket kept their oysters cold from farm to display. Qiu suggests chipping in with some neighbors or friends to save on shipping fees.

As the tour and the shucking seminar came to a close, Saul Ranella presented our final cocktail: a vesper cocktail made with Humboldt Organic vodka, a house kina, and dry vermouth blend, with nori and two kinds of roe (smoked trout and paddlefish caviar). Normally I probably wouldn’t go for a drink with two kinds of fish egg and seaweed in it, but everything about this weirdly freezing July day in California telegraphed that this wasn’t a normal day. It was an experience; a ritual. And under the circumstances, all that brine hit the spot, the perfect accompaniment to some barbecued Sweetwater oysters.

If you’re at all oyster curious but on the fence, I’d recommend barbecued oysters as a gateway. For a while when I was younger, I ate raw oysters mostly as a way to prove that they didn’t gross me out, even though, admittedly, they have a not un-snot-like texture. After a while, they became a vector for horseradish, and a while after that I came to genuinely enjoy the flavor of raw oysters themselves (preferably with a nice mignonette). Oddly, the rawer and fresher a seafood, the less “fishy” it tastes. And raw oysters are about the rawest, freshest seafood you can eat.

Of course, a raw oyster is still going to have that snot-like texture. If you haven’t learned to love that yet, a barbecued oyster is a happy medium. If you grill an oyster just until the shell pops open (they make a nice sizzle when they do, which is fun), then pull the lid off and throw some garlic butter or something in there, you get an oyster that’s cooked just enough to have some chew to it, but not enough to get the fishier, muddier taste that oysters can sometimes take on when they’re cooked too much. I don’t love them quite as much as fresh raw oysters, but they’re pretty close.

It was still cold enough for a jacket by the time we left in the early evening, the hours that are usually the hottest part of the day in a NorCal summer. After consuming at least two dozen oysters, I felt weirdly energized. Eating anything else in such quantities would put me to sleep. 15 minutes into the drive home, our cell phones vibrated back to life and the hot sun clicked back on, unmistakable signs that our reverie was over and we had entered real life again. Probably another language has a word for this feeling, German or Russian. Would it someday be possible to recapture the feeling of that escape? Could we conjure it back into existence with a simple ritual? Find it in a cocktail glass or inside a shell?

*Like your mom

**Like your mom

—

Vince Mancini is on Twitter.

This trip was hosted by Humbolt Distilling, though they did not review the story. For more on the Uproxx press trip policy, see here.