If anything, the 20 years since the release of Election have only further cemented its place as one of the all-time great comedies. The root of comedy is surprise, and in a genre that’s so reliant on newness and topicality, any work that retains its humor beyond a few years is impressive bordering on the miraculous. Election, released in April 1999, is notably still funny. Really funny.

How does a comedy become timeless? Part of Election’s greatness is that it’s so irreducible. Almost every laugh is the sum total of composition, editing, performance, writing, music. Where so many other celebrated comedies over the years have marked the emergence of some great performer, or the comedic awakening of a particular generation, Election just feels beautifully designed, everything in it working just so.

I laugh as much at the framing, editing, and music choices — the iconic freeze frame of Reese Witherspoon’s nostril, the floating heads exhorting “fill me up, Mr. M” — as I do Chris Klein’s aw shucks delivery of voiceover lines like, “My leg wasn’t bugging me too much and the weather was so nice, and every day after school Lisa and I would go to her house to fuck and have a hot tub.”

With 20-year-old comedies, you often get a sense of “they don’t make ’em like that anymore” or “they’d never get away with this today.” Consider that another 1999 hit comedy released a few months after Election, American Pie, had an entire scene that revolved around filming the foreign girl changing and broadcasting it to the entire neighborhood (featuring a Blink 182 cameo). And when the video accidentally went viral, the filmer was shamed not for being a sex offender, but for ejaculating too early.

Election, by contrast, has a keen sense of morality and is only funnier for it. Probably because above all it eschews self-righteousness. It practically makes a fetish of eschewing self-righteousness. You don’t get the sense that it couldn’t exist today or that the jokes couldn’t be done, only that jokes today mostly lack Election‘s nuance and panache. Movies as thoughtful as Election are a rare commodity in any era. All of its characters are so flawed and so relatable, and they come together in ways that feel novel yet deeply true. It may contain the world’s only “hilarious admission of statutory rape” scene.

Stylistically, Election is a mix of retro and classic techniques — the freeze frames, the character theme music, the insets, the voiceovers — combined in ways that feel fresh. It’s about as close as it gets to a “symphony” in comedy movie terms. Election is a comedy that is undeniably Art, where we invoke art to explain the presence of laughs rather than a lack of them.

The High School Movie That Isn’t

Cue the part where I tell you it wasn’t appreciated in its own time.

That’s true, though only if we narrow “its own time” down to the few months following release. Tom Perrotta wrote the book on which Election was based, still unpublished when the film began shooting. He’d connected with a film producer who’d seen Perrotta at a public reading, who eventually read Perrotta’s manuscript for Election, and helped him get it optioned by MTV. As Perrotta told The Guardian, “It all looks like a very good career move in hindsight. The truth is, Matthew Broderick was in a career lull at the time, Reese Witherspoon had never had a hit movie, and although the film was a critical success, it was box-office death. No one ever did an R-rated teen flick again.”

Director Alexander Payne, fresh off 1996’s Citizen Ruth at the time, wasn’t even interested in it, initially.

“The novel came to Jim Taylor and me as a job,” Payne told me via email. “MTV Films, under the aegis of Paramount, had optioned this book and two recent friends of mine, Ron Yerxa and Albert Berger, were producing. I put off reading it for a couple of months, because the last thing in the world I wanted to do was a high school movie. Finally, I read it and saw it was much more, and Jim agreed. I liked the humor, the banality, and the formal challenge of doing multiple voiceover.”

Maybe that’s why it’s hard to even think of Election as a “high school movie.” If any movie where teens are the main characters is considered a “teen movie,” Election is the greatest teen movie of all time. It feels much more like a movie about human nature, a suburban gothic, much more of a piece with the movies Alexander Payne would go on to do — Nebraska, Sideways, The Descendants — than anything that had come out up until that time. And innovation traditionally presents a challenge to marketing.

“The movie came out in April, was not marketed very aggressively, and didn’t make much money at the box office,” Payne says. “Just double its $8 million budget. But the reviews were terrific, and a few months later the movie won a bunch of awards, and Jim and I got our first Oscar nomination.” He added, “It’s still the movie I get the most compliments on from film nerds, and I think it’s the only movie I’ve ever made that’s not too long somehow.”

And while we may have lost R-rated teen flicks for a while, Bo Burnham made one last year, winning a handful of awards in the process. With its inspired editing and theme music for individual characters, Eighth Grade feels like a direct heir to Election. It probably won’t be the last.

The Gods’ Playthings

“The pitfall of making a comedy with a studio, it’s probably an American cultural thing, but I get tired of being encouraged to always go for laughs. When you’re going for poignancy, patheticness, there can be forces pulling you to go for laughs, and to abort the serious moments. And that’s something that I have had to be on guard against.” -Alexander Payne, to Combustible Celluloid, 1999

One of the most striking aspects of Election is that most of its funniest moments come in scenes when its characters are the most sad.

“I think that applies to almost all the pictures I’ve directed,” Payne told me. “Hell, Chaplin played a homeless guy.”

Even so, Election seemed to set the standard. Paul Metzler tumbling down a ski slope, breaking his leg and scuttling his promising football career in flashback, screaming “WHY?!” Dave Novotny blubbering “we were in love!” in response to Principal Hendricks asking “Did you ever cross the line with this girl?” Jim McAllister getting stung by a bee while trying to set up an extramarital liaison. Tracy Flick falling to pieces after losing the election. All moments of devastating, life-changing sadness, all extremely funny.

Tammy Metzler’s heartbreak is probably the most legitimately wrenching of the film, having had her first love, Lisa, not only dump her for her brother, but pour salt in the fresh wound, telling her, “I’m not like you, I’m not a dyke.” Tammy stands in the driveway, tears in her eyes as she watches Lisa speed away, and even that moment is so over-the-top cruel that it almost transcends sadness and becomes a meta joke.

Most of those moments existed in Tom Perrotta’s book, but it took Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor to turn them into a parade of painful laughs. No one has made the quiet desperation of suburban American life so central to his work. The downtrodden are never just lovable underdogs in Payne movies. The smart ones are always a little pretentious, and the “happily ever after” setting of so many other stories that assume suburban bliss is always filled with people who are deeply unfulfilled, even if they themselves don’t entirely know it.

Matthew Broderick’s Jim McAllister is a perfect example, a guy who thinks he’s happily married until his friend’s wife suddenly seems like a viable option. He loves his job yet resents his star student Tracy for reasons he can’t quite face or explain.

For Perrotta, the story grew partly from watching the 1992 presidential election unfold (Tammy Metzler was meant to be the Ross Perot) and partly from teaching a generation of women he found intimidating.

“I was writing about my own generation of women,” Perrotta told Vox in 2017. “I went to a working-class high school, and then I went to Yale, and I met all these women who had been empowered in a way that a lot of the girls I had grown up with hadn’t been. They felt that the world was wide open for them. And then I went and I taught at Yale and Harvard for 10 years after that. I was just teaching freshman comp but meeting all these powerful young women, and I did have this feeling of, this is something new.”

“They were scary to a lot of men, I think, and at least I think I put my finger on that sort of ambivalence that came from encountering these women. I love that Tracy is subject to revision right now, that feminists have rediscovered her and are starting to defend her. For years and years, there was this sense that Tracy is a monster, and I never felt quite like that. I felt like Tracy makes some mistakes, but there’s something really human and admirable about her.”

There’s a lot wrong with the “Tracy as feminist hero” read of Election, but it is interesting that Election consistently depicts the men as the dreamy, emotional ones. Tracy Flick just wants someone to treat her like a person; Dave Novotny immediately assumes they’re in love and that she wants to run off together. Linda Novotny wants companionship; Jim McAllister assumes they’re going to have a sexy affair. The male characters in Election tend to treat the women more like cures for their boredom than people.

As Payne told The Talks in 2012, half the reason he did the film was for a single shot of McAllister, a shot that “so cracked me up that I wanted to have a whole film just for it.”

“There’s a guy who’s preparing to have an illicit affair in a cheap motel and he goes to that motel to make everything just right,” Payne said. “He puts some champagne in the sink with ice from the ice machine and he puts out Russell Stover chocolates. And then there’s the shot where he gets into the bathtub and he washes his ass and his balls and his dick. He’s squatted over in the bathtub washing himself. The whole film was pretty much just for that shot.”

It’s also interesting that Tracy Flick became an insulting (or complimentary, depending on whom you ask) comparison for Hillary Clinton in 2008 or 2016. It was actually her husband, Bill who was Tracy’s inspiration.

“I was obsessed with the 1992 election,” Perrotta tells Vox in the same interview. “That idea of Bill Clinton and the character issue. As a novelist, I just thought the disjunction between who we are internally and who we want the world to think we are, that is the crucial question of the novel. The idea that the American public was crying out for the banishment of the private self struck me as completely wrong.”

The Seinfeld writer’s room famously had a “no hugging, no learning” rule for its characters. Payne has a much greater capacity for delving into non-laugh emotions than Seinfeld (partly because he works in a medium that allows for it), but the root of virtually every laugh or interaction in Election is that existence can be arbitrarily cruel.

“When I asked whose point of view to take in Election,” composer Rolfe Kent told me over email, “my recollection is that I was told that the characters were ‘the gods’ playthings.’ The music then became the wry perspective of the “gods.” It became about the convoluted knots the characters got themselves in.”

The appeal of Election is part sadism, watching Perrotta and Payne and his co-screenwriter Jim Taylor meticulously destroy their characters like a kid pulling the wings off a butterfly, and part recognition. We see a bit of ourselves in characters like Jim McAllister, such that when he screws up and everything goes wrong for him, we’re both invested emotionally, and get the kind relief that comes from waking up from a bad dream.

“I’m flawed too, but at least I never did that.”

Finding Joy

Part of the reason watching Payne and company destroy their characters is so enjoyable is that they seem to be having so much fun doing it. If Election‘s characters are all having varying degrees of a bad time, everyone who worked on it seems to be having a blast. Filmmaking is such a collaborative process that it’s easy for a good story and good intentions to go awry, and create the kinds of movies that make you wonder how good movies ever get made.

But every once in a great while you get a film where everyone involved seemed to take what was on the page and add their own creative flourish to it, and the final product was only the better for it. That’s Election.

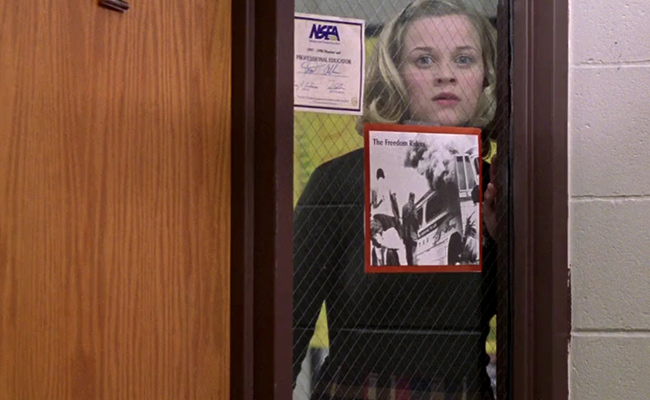

One of Election‘s most memorable moments is its introduction of Tracy Flick. Jim McAllister is presiding over his history class, asking the students if they can explain the difference between “morals and ethics.” Everyone struggles, including one kid who just starts and then stumps himself mid-sentence (one of the best things about Alexander Payne is the way he refuses to romanticize youthfulness or make his high schoolers “cute” in any way) while Tracy Flick jabs her raised hand around wildly, begging to be called upon.

When McAllister finally gives in and lets Tracy have her say, the scene pauses with an awkward freeze frame on Reese Witherspoon’s half-closed eyes, sideways mouth, head tilted back to display one gaping nostril, all narrated from McAllister’s perspective. From there we telescope into Tracy’s history with Jim’s friend, Dave Novotny, which is actually narrated by Tracy, in a voiceover-within-a-voiceover, explaining who she is and how she got involved with a teacher. The montage-within-a-flashback goes on for almost 10 minutes, almost long enough for us to get unstuck in the film’s timeline, concluding with McAllister telling his friend that what he’s doing is wrong and trying to talk him out of it.

NOVOTNY: I don’t a lecture about ethics.

MCALLISTER: I’m not talking about ethics, I’m talking about morals!

NOVOTNY: …What’s the difference?

Ba-doomp chsssh.

Stylistically, this sequence is Election‘s approach in a nutshell. Payne mixes classic, almost old-timey techniques in a novel way, and keeps finding new inspirations and new jokes along the way.

“The freeze frames actually were scripted,” editor Kevin Tent told me in a phone interview. “But I do remember… when I first did my assembly, I took more straight-faced, normal freeze frames — at least in the first one. And then when [Payne] got in, he was like, ‘No, no, no. Let’s find the goofiest shot of her and use that one.'”

“Kevin and I just found that unflattering freeze frame one day in editing, and it cracked us up,” Payne told me. “I said, ‘Let’s go with it,’ and Kevin said, ‘Wait till you get a call from her manager.’ But it wasn’t just funny; it was thematic. It was how her teacher saw her.”

That willingness to “yes and” your own creation suffuses Election, and it’s a staple of comedy in general. It’s how we get riffing, memes, mashups — jokes that build and snowball and call back. That Election does it so well speaks to both its creators’ willingness to do that kind of riffing, and to their freedom to do so. They had the inclination, but just as important, they had the time.

You’ll often hear filmmakers say that the biggest difference between a bigger budget movie and a smaller budget one is time. More so than flashy effects or big movie stars, what that bigger budget buys you is more time to shoot. Election didn’t have a huge budget, but because of a quirk in the way it was released, it did have time.

“[Payne] had a vague notion, I think of how he wanted it to be,” Tent says. “And then we just kept working at it, we cut for a really long time on that movie. We cut for almost over a year. About a year and couple months.”

“We had two Christmas parties in the cutting room on Larchmont Boulevard,” Payne says. “It was the first and only time that Jim and I have re-written and I re-shot an ending.”

According to Tent, the normal time frame for editing a movie like Election would’ve been six or seven months. The movie ended up getting twice that.

“The studio, really Sherry Lansing, to her credit, really pushed for us to shoot a new ending,” Tent says. “The original ending was more poignant. And it didn’t really fit in the movie and I like to say that, the ending of About Schmidt, if you’ve ever seen that, is what he tried to do at the end of Election — try to get serious and have it be meaningful. But the audience just wasn’t having it. They were clapping through the whole thing and having the best time. And then when we got serious on them they were like, ‘What? We don’t want that.’

In the novel, Mr. McAllister ends up quitting and working at a car dealership, and the movie initially was much more faithful to that. The original ending was actually discovered in 2011 on an early VHS workprint that somehow found its way to a flea market.

As you can see (for as long as the video stays online), Tracy goes to see McAllister at the car dealership where he now works, ostensibly to buy a car for college (a ’90s Ford Escort, my God were those ugly hunks of crap) but actually to have McAllister sign her yearbook. You can sort of see what they were going for. It’s almost like they wanted to make sure we know that Tracy isn’t the villain, but we get that at the expense of pacing and tone. It’s probably too maudlin and definitely too long.

“The original ending you can read in the novel, but the movie turned out a lot funnier than the novel, so that first, more melancholy ending, felt out of whack,” Payne says. “Jim and I asked ourselves what ending we might have written had it been an original script, and it worked.”

In the reshot ending, the scene builds to a head, McAllister trying to be generous and wish Tracy well, even just in his own head, but eventually thinking “who the fuck does she think she is?” and throwing his milkshake at her limo. Our last image of McAllister is him running away from the camera, while someone offscreen yells “you asshole!”

The last time we see Tracy, she’s sucking up to some asshole politician. It feels much more “right” that the movie should end with Jim still being petty, and Tracy having gone into politics. How much less memorable would Tracy be if our final image of her was just a nice college girl getting her yearbook signed?

And like almost every scene in Election, it ends on a perfect comedic “button,” wrapped up in a nice little self-satisfied bow. It’s the same way the characters seem to like to think of themselves.

(One note of trivia: the pizza place where Tracy Flick and Dave Novotny first connect is Godfather’s Pizza, run by future presidential candidate and Pokémon movie quoter Herman Cain, who acquired the chain from Pillsbury in a leveraged buyout in 1988. I mention it because Herman Cain seems like a perfect Alexander Payne character.)

Nobody’s Perfect

For me, the legacy of Election is that none of the characters are entirely sympathetic. They all have their positive qualities and they can all kind of be assholes in their own way. #TeamMcAllister or #TeamTracy is kind of missing the point (and I’m ride or die #TeamTammy, if it ever comes to that).

There’s always a tendency to write people as we want to see them, rather than as they are. The latter always seems funnier, to me, and with a more lasting appeal. We see the characters in Election, and get to know them through their own thoughts, but even in time of their most earnest self-reflections, they don’t entirely see themselves.

Paul Metzler (Chris Klein should’ve won an award), largely the lovable idiot, so self-effacing that he can’t bring himself to vote for himself in the election, in contrast to Tracy’s craven careerism, is sympathetic in a lot of ways. His over-the-top reaction to seeing Mr. McAllister at the crappy restaurant remains one of my favorite moments of the film, (partly because it shows how child-like exuberance can be annoying). But the most telling (and funny) Paul line is the end of his prayer: “Forgive me for my sins, whatever they may be.”

“Nice guy” though he may be, Paul’s still totally incapable of even imagining himself as anything but the good guy. All the characters are like that to some extent. In fact, I wonder if part of the reason Election is such a successful book adaptation is that Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor were capable of seeing things about Perrotta that Perrotta wasn’t entirely able to see about himself.

Perrotta wrote the book partly based on his experiences as a teacher. Mr. McAllister is the teacher in the story, the movie opens in Mr. McAllister’s perspective, so it’s natural to think of McAllister as Perrotta’s stand-in, or the closest thing to it. The reason the film ending with McAllister throwing a milkshake feels more “right” than the one of him signing a yearbook isn’t just because it’s snappier and funnier. It’s more honest about who McAllister is. It shows his better nature, him trying to be gracious, and also where that graciousness ends. Election is about the moments where the mask starts to slip.

The film does the same things with all the usual myths of Americana — our ideas about democracy as a utopia, about the heartland as a wholesome, pious place free of pretension, and about jobs and families as end goals where ambition ends. It’s not a takedown, as the characters are almost all as admirable as they are occasionally amoral. It’s just honest about where exactly the bullshit ends and reality begins, where the true face peeks through the public mask.

There’s the “America” we write songs and stump speeches about, and then there’s Election, the awkward freeze frame of America’s nostril.

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.