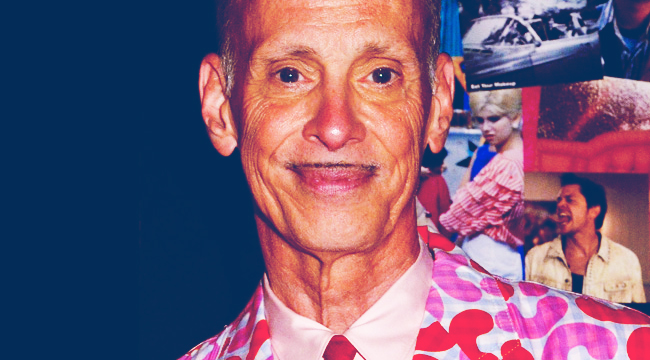

It’s been 15 years since John Waters released an all-new cinematic assault on stodginess (or whatever else wound up in the provocative filmmaker’s crosshairs), but the pencil-mustachioed Baltimorean hasn’t exactly been off in a corner somewhere. As Waters explained when we recently spoke with him, he’s keeping busy. What’s new? An interesting pairing between his recognizable voice and a sci-fi idea from screenwriter Les Bohem’s (The Darkest Hour) mind in the form of Junk, an Audible audiobook (available to download now) about an alien conspiracy theory and the very fabric of humanity.

Though Waters is, admittedly, not the first name you think of when you think about hard sci-fi, he nevertheless brings Junk to life across a unique 10+ hour narration/performance. But what caused him to align with such a non-John Waters-y seeming project, does he feel creatively fulfilled without a camera in his hand, what’s changed about “Hollywood” since he last directed, and can camp be faked? Waters has something to say about those topics and more below.

How did you get involved with this project and what was it about Junk that connected with you?

Well, I had an agent that sent to me to Audible to have a meeting about overall things, and then they called and asked me to do this. I have done all my own books on… books for tape, that’s what they used to call that. I’ve done a lot of voiceover work on animation and that kind of thing. But I’ve never actually read someone else’s book. So I thought it was a new job description that I thought would be interesting and something I wanted to try. Junk was something that was very different than what I usually read. I’m not a big science-fiction buff or conspiracy theorist or any of this, but I liked it. It was a challenge to me. It was a genre that I didn’t know and it also felt very much like a movie to me. I loved the idea that these kinds of Audible books, they don’t come out as books. They only come out as spoken word things. So basically that’s like a new concept that seems very modern, so I wanted to try it.

How much communication is there between you and Les Bohem, the author? How much direction is there?

Well, he was certainly there and I talked to him before, and of course, before I did it, I read the book twice. It’s a long book and it’s a complicated book, so he was definitely there to explain things to me if I didn’t get it or anything like that. But he was a fan of mine and so it was very nice to have him there. I wanted him to be there. It helped a lot.

In terms of the performance, how do you make it your own?

Well, you try to make it your own by, you know, you have to play different parts. Now, obviously, you’re not going to go into a different voice for every single character that’s in the thing, but you do have to distinguish those characters when you’re reading. I want directors to tell me… don’t mind line readings. Actors hate line readings in movies, but when you’re reading a book, sometimes they really help because I know when someone else is reading my dialogue, in my mind, I’ve already said it a million times, so I know how it’s supposed to be said. So I’m eager to have the author’s input.

Do you get the same level of creative fulfillment as you get with filmmaking with this and your art?

Well, what I do in all the jobs that I have is [I’m a] storyteller. I do spoken word shows. I do John Water’s Christmas, which I did 17 shows this year in 21 days. I play horror conventions. I play music festivals and I write movies. Maybe they don’t get made, but they pay me to write them still, which is fair. That’s part of the deal. I think you can never have too many careers, so this is just another career to add, something that I have now done and we’ll see if it leads to more.

You say you’ve written scripts. What has changed in the movie industry [since your last film]?

It’s completely different. I mean, when I pitched movies there were fifteen companies and an average independent movie was five or six million dollars. Today, there are about three companies and you’re lucky if you get a million. So, it’s harder… I think it’s much harder for people to get independent films made today. There’s a saying in Hollywood, the more money they give you the more grief you’ll get. That’s a mathematic algebra that always proves to be correct.

With Junk, when I said it’s a like a movie… It would be a very expensive movie, which is kind of fun when you write. That’s one thing I know when I write books, I don’t have to worry how much it would cost to do the actual thing I’m writing. So that, I think, is a great relief to any author that’s writing a novel of any kind.

Would you ever want to make a big budget, huge movie? Like if a Junk movie came to fruition.

Well, sure! I mean… I don’t have any interest in, like, these movies that China makes with no movie stars — just all special effects and barely any dialog. You know, that’s not what appeals to me. That’s more of a science project. I think the biggest budget I ever had was on Serial Mom. I think we had thirteen million, which you know, I had enough to make the movie look the way I wanted it to look. But that’s not a big budget today at all. It just came out, a beautiful new version on Blu Ray. My films keep getting rediscovered and re-released and Criterion editions for Multiple Maniacs and they’re doing Polyester next. So they all seem to have a life on their own. They keep coming back.

Specifically, with Serial Mom, it’s still so relevant with our continuing true crime obsession.

It was a parody of true crime before true crime was that popular. That was the problem we had at the box office when it came out.

Is that surprising to you? That we’re still stuck on that, culturally?

No, nothing surprises me.

You’re not really super into sci-fi but has that always been the case? Any connection to the sci-fi movies from your childhood? ’50s and ’60s sci-fi?

The ones I always liked were the ones that were kind of bad. You know, like Queen Of Outer Space and Earth Versus The Flying Saucers and all of them but even as a child I knew they were so bad they were great. I don’t think Junk is that at all. I think it works for the genre that it is.

Some movies try to be campy but they just… you can tell that they’re trying too hard to be campy.

I usually hate those movies, because they’re trying too hard. You can’t try too hard. That’s the one sin that eliminates greatness from anything.

You can listen to John Waters narrate ‘Junk’ on Audible now.