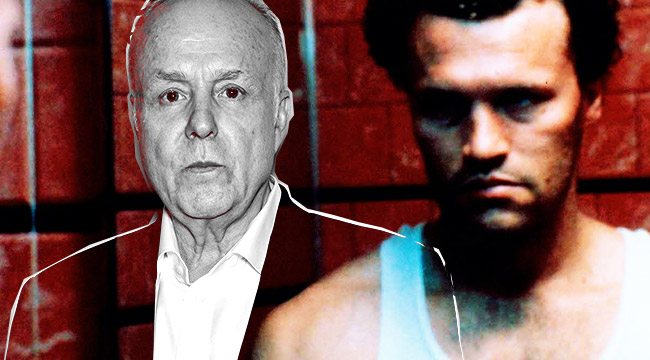

John McNaughton is a fascinating filmmaker who’s done everything from work with giants like De Niro and Bill Murray on Mad Dog and Glory, to exploring Beat culture with the documentary Condo Painting, to directing the ’90s cult classic Wild Things. But it all started with a horror movie so real Hollywood was afraid of it.

Henry: Portrait of A Serial Killer was, for a long time, an elusive cult movie. It spent several years looking for a distributor before finally scoring a release — and both controversy and acclaim — in 1990. The film stood in stark contrast with the jokey murderers and campy hockey-masked death machines of the era’s horror movies, thanks in large part to Michael Rooker’s unnerving portrayal of the title character and McNaughton’s documentary-style filmmaking. Over time, though, the film found a devoted audience thanks to home video. It’s currently making a return to theaters thanks to a rerelease of restored 4K version just in time for Halloween. McNaughton was kind enough to speak with us about how Henry was made, and how it struggled to get seen.

This came about because a documentary fell apart, right?

I had made one documentary, actually two, but one that was remembered [Dealers In Death] and it was constructed from a lot of public domain footage and photographs. I knew somebody who had a cache of old footage of wrestling, Moose Cholak and the like, which were very popular in Chicago. There was a deal put in place, I don’t remember what the price was. But when the owners of the footage realized we had some money, they said “We didn’t mean ten, we meant twenty” and we said “get lost.” So I was going in to visit the Ali brothers [executive producers Malik B. Ali and Waleed B. Ali], because this was going to be my living, and one of them said “I tell you what. You had this dream, I’ll give you a $100,000 to make a horror film.” This was my shot to make a film. And that was the inception.

I know there’s a lot of friends, family, and even just bystanders in the movie. How’d you explain the movie to them at the time?

I’ll have to explain it to some tonight! They’re more normal citizens of America! [Laughs.] They were all pretty good friends. They all knew that I was half-nuts and anything I did was disreputable.

I’m told the fence who gets killed was something of a legend in the video days.

The guy that gets the TV whacked over the head, Ray [Atherton] is a very interesting character in real life. From childhood, he was a film collector, and when video came around, he became a lay lawyer in public domain law. For example, Night of the Living Dead was in public domain, and everybody who was in video wanted to sell it. Ray happened to know what was in the public domain, and he would find them the best prints. He was a defendant in the first video piracy trial, because when you couldn’t duplicate film prints, nobody cared. But once you could duplicate it and make money off it, people did care. He was up on 42 counts of piracy! And won! [Laughs.]

There are some notorious stories about how bystanders got involved in the movie.

We were shooting a scene where Becky (Tracy Arnold) has her interlude walking down the street looking in the windows, and there’s a stairway that leads to the El-train. And there were two guys just standing there just yakking and yakking. If you were making a real movie, you’d pay them to leave. But we couldn’t, and they didn’t care, so they’re in the movie. And there’s a bit where this woman just walks right out of a store in an insane leopard skin coat that looks like we placed her, but we didn’t! [Laughs.]

While the movie is based on Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole, it’s not an exact one-to-one. How did you choose what to focus on?

Richard Fire had more experience writing scripts than I did, and it was mostly for plays. I deferred to him often and learned very much. The scenes where Michael and Tracy are talking from the heart… they’re terribly damaged and not terribly sophisticated people, but don’t ever make fun of them. Sometimes I hear those conversations in my head, and they’re so important to the success of the movie.

Did you have any theater or film background when you started?

Not at all. Not one iota! I hate to say this, but I went to art school. The last thing you want to tell anyone in Los Angeles is that film is an art form, they’ll run you out of town quickly. Over the last couple of years I have worked in theater, because what I think I’m best at is getting performances out of actors. We did Danny and the Deep Blue Sea, with Juliet Landau and Matt Williamson and spent less than $200 on it. It’s wonderful to work with the actors and deal with their humanity, not to deal with crew and tech. I really enjoyed it, and I’m getting ready to adapt a Jack Kerouac novella.

Michael Rooker and Tom Towles had to go to some bleak places, as actors. What was that like as a first-time director?

We rehearsed for two weeks, and they went home and wrote biographies. We took sentences from them and wove them into the script. The scenes had been run and the dialogue had been polished and by the time they got there, everyone knew what they were doing. Everything was professiona;. Michael would stay in character and hide between scenes, so he wouldn’t come out and have to get back.

Have you stuck with that idea, prep first, then shoot?

I leave actors alone in between mostly. In a scene with Robert De Niro and Bill Murray, stay out of their way! [Laughs.] I don’t direct actors as much as I prepare them.

Henry struggled to get into theaters for years. When did you finally break through?

I think it opened in Boston in ‘89. Those were some bleak years. We had video cassettes of the the movie. After the movie was completed I went 18 months with no income whatsoever. I was living at my cousin’s house. I had credit cards and money from the picture but eventually I was flat broke. If memory serves… Did you ever hear of a company called Vestron? I had a friend who had a friend who worked for Vestron, I was in Manhattan, he had a party and we showed the film. He brought it the next day, they made a deal to distribute it theatrically and on video. I went out and bought champagne… and then Vestron dithered. And after six months of waiting waiting waiting, they came back and said “Is Henry is that real guy?” I said “Yep!” “Oh, well, our legal department…” and they backed out of the deal.

Just like that? They were afraid of being sued by serial killers?

[Laughs.] And it was all based on court proceedings and public records! They were fair game, they were convicted murders, and all the information was publicly out there. Years later I learned they couldn’t give a s***, they were just afraid of it. It was just too much, they went back and forth and they didn’t want to be associated with that film. But eventually there was this little company. This couple had met at Vestron, and started their own company and distributed. They got David [and his wife Suzanne to do a small release in the US, they took it out on video, and they made a fortune. It did very well.

At the time the reaction was hugely controversial. Did you get any fallout from that, any lawsuits or angry letters?

I didn’t get any angry letters, but I got weird ones. I think Michael crossed paths with some people. I’d get letters and stuff from people saying “You really love Henry like I do!” and I was like “Hhhhhmmmmm… Don’t send me any more letters!” [Laughs.]

There’s an almost New Wave sensibility to the filmmaking of your early work, just taking to the streets and shooting. Did that cause any friction with Hollywood executives and the like?

[Laughs.] The second movie I made was The Borrower. We had Tom Towles [Ottis Toole from Henry], as somebody who gets his head ripped off by the alien and just plopped on his neck. There’s a huge scar on his throat, he’s covered in blood, and we just let him walk down the street through the crowds in LA. And in those days, LA was full of really low-rent crazy people.

We had a 400mm lens, so we were way far away. Nobody batted an eye, some people just sidelong glanced. We were just seeing real human beings watch this monster walk by. My producer was fidgeting and finally he burst out “I hate this type of filmmaking!” He wanted control. I just looked at him and said “I f***ing love this kind of filmmaking.”

Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer opens in limited release tomorrow.