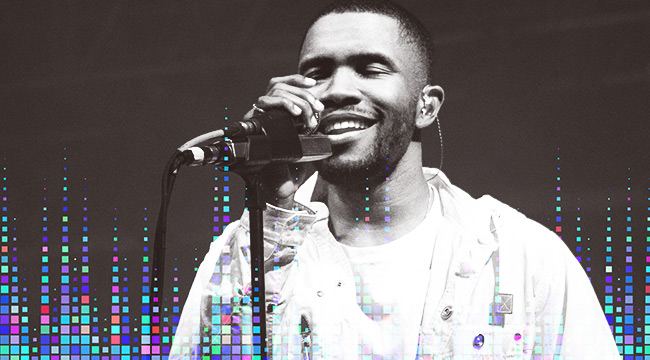

On Friday, barring any additional delays, Frank Ocean will finally release his second studio album, Boys Don’t Cry. It’s been a long journey to this point — Ocean’s previous LP, Channel Orange, came out in July 2012, a distant time when people still looked forward to summer movies and establishment Republicans supported their party’s presidential candidate. In terms of the music industry, the four-year gap between Frank Ocean albums feels even longer. It remains to be seen how the passage of time has impacted Ocean’s art. But as far as how Boys Don’t Cry will be heard, Channel Orange already feels like it belongs to a different decade.

As the New York Times first reported on Monday, Boys Don’t Cry will be available exclusively via Apple Music for the first two weeks before matriculating to other streaming sites and retailers. This sort of deal is now standard for big-ticket records — the Times story noted that Apple Music recently made similar arrangements for albums by Drake, Chance The Rapper, Future, and The 1975. Negotiating a temporary — and in a few cases, permanent — monopoly on a blockbuster LP has become the primary strategy for competing streaming services trying to distinguish their otherwise largely indistinguishable music libraries.

Presumably, Boys Don’t Cry will also be available for download at the iTunes store, similar to how Channel Orange was initially an iTunes exclusive in 2012. However, digital downloads in 2016 are now such an afterthought that Apple had to put out a statement in May denying a report that downloads could be discontinued in as soon as two years. But no matter Apple’s protestations, the numbers spell almost certain doom: In the first half of 2016, about 404 million downloads were sold, down 42 percent from the best ever year for downloads, 2012, when they were nearly 700 million downloads sold.

Given present trends — more people streaming, fewer people downloading — it appears that the days of average music consumers owning personal collections of songs and albums are numbered. Just from a simple logic perspective, it’s clear downloads have outlived their usefulness for many listeners: Why pay for individual downloads when streaming gives you so much more bang for your buck, while also offering virtually the same listening experience?

Was any of this foreseeable when Channel Orange was released in the midst of relative boom times for digital downloads four years ago? Perhaps — after all, Spotify launched in the U.S. almost exactly one year earlier, in July 2011. However, for those of us who wanted to hear Channel Orange immediately in the summer of 2012, paying for a download from iTunes was the only (legitimate) avenue. And lots of people downloaded that record — Channel Orange debuted at No. 2 on the pop chart, moving 131,000 units, in spite of it being available only on iTunes that week.

Even now, the release of Channel Orange stands as one of the most momentous “event releases” of the ’10s. Along with Radiohead’s The King of Limbs and Jay Z and Kanye West’s Watch the Throne, Channel Orange was among the first pop records to harness the power of social media as a hub for fans to to share their opinions about a major release in real time. Persistent fears about the internet destroying “monoculture” were instantly rendered irrelevant, meaning if you cared about Channel Orange, you could feel like you were part of something bigger again.

This social media aspect of blockbuster albums hasn’t changed, though what once seemed refreshing (“Wow, I can see hundreds of takes on this thing I’m just now hearing!”) has come to feel exhausting. (“Ugh, how are there already hundreds of takes on this thing I’m just now hearing?”) What is different now is a subtle but monumental shift in how many people access music. Right now, the era of digital downloads is looking more and more like a discrete period of time that will have lasted barely 20 years. But if digital downloads truly are on the way out, then it will also spell the end of a much longer period when ownership was a meaningful concept for the majority of music fans.

In 2012, people still acquired albums that they could subsequently play whenever they wanted. In 2016, however, listeners have traded this control of their favorite LPs for access to a seemingly boundless supply of music. Whereas music fans owned Channel Orange — if you bought it, you could play it on an iPod, burn it on a disc, or share it with friends — Boys Don’t Cry will technically belong to a distribution channel that allows subscribers to listen for a monthly fee.

Of course, for now, Boys Don’t Cry will also be available for purchase for those who want it. But we’re fast approaching a time when albums will primarily be streamed — plus the vinyl version, maybe, though most people won’t be buying turntables, even considering the rising number of sales. Otherwise, alternatives for those of us who like to have personal libraries will be limited. So it’s worth asking: What will this mean for music fans?

“We give up control, they give us choice and convenience” is what millions of us have happily signed up for. Personally, I have zero nostalgia for iTunes. Shopping there was cold, impersonal, and above all not fun. If I’m being honest, MP3s became a lot less exciting to me once Napster came and went. The initial thrill of downloading was tied to the adrenaline rush of mass, indiscriminate consumption. Like so many people, I would stay up all night inhaling music into my hard drive that I knew I would never, ever listen to. But listening was never the point of downloading for me; it was consumption for consumption’s sake. I was high on my own improbably massive music supply. Of course, like a lot of addicts, I had to break the law to get my fix. At some point, downloading felt seedy, and a combination of my own ingrained morality and the malware embedded in illegal MP3s hastened my rehabilitation.

If downloads were like heroin, streaming is methadone. Streaming satisfies the same strange, self-defeating urge to accumulate millions of songs that you’ll never have time to hear, but without the mechanical, time-wasting strain of actual downloading.

But like all changes in technology, streaming has garnered some pushback: Is it possible that we have too many choices now? This view was expressed eloquently in a recent elegy for the departed iPod Classic by The Ringer‘s Lindsay Zoladz: “At the risk of sounding like a total geezer, I can’t help but feel that we’ve long since crossed the threshold of that magic number, into the realm where there’s simply too much music, too many tweets, too much stuff out there to feel anything but overloaded and paralyzed almost all of the time.”

It’s easy to relate with Zoladz in not just the feeling of being overwhelmed by the daily crush of content, but also the defensiveness about sounding like “a total geezer” if you don’t totally embrace new technology. However, I’ve come to be more bothered by the opposite problem: the ways in which streaming creates the illusion of limitless choice while also restricting options that listeners only recently surrendered.

It’s important to note that the widely circulated idea that streaming services offer “everything” is a myth. We all know about the big-name artists — Taylor Swift, Adele, Beyonce, Radiohead, Coldplay, Neil Young — with a fraught, on-again-off-again history of making their music accessible on streaming sites. Less known are scores of records that haven’t been digitized and perhaps never will be. And then there’s the possibility of whatever’s available on your streaming channel of choice not being there tomorrow.

This always seems to be forgotten: An artist or record company can pull your favorite album at any time, and put it either on a different distribution channel or take it completely off the grid as a negotiation ploy. An album that in a different time would’ve resided safely on a private shelf or hard drive can now be snatched from the celestial library and held for ransom. It seems likely that this will become more common as music fans become increasingly reliant on streaming services. Our love of music will be used as leverage.

In a stream-centric world, the only music that seems to exist is what’s on streaming services. We’re only a few short years into streaming being a mainstream phenomenon, but you can already see the psychological impact that the “Spotify has everything” myth has had on listeners. When Prince died in April, several media outlets felt compelled to educate readers on where to locate Prince’s music, even though his albums were readily available on iTunes and Amazon. (“It’ll cost you,” warned the Hollywood Reporter ominously about downloading Prince’s albums.) But because Prince kept his music off most streaming avenues (save for Tidal), people were mystified about how to hear it. “Why would I bother owning an album?” seemed to be the unspoken question.

Some choices are indeed bountiful. But other choices have been taken out of our hands: If you want to hear Frank Ocean’s album this week, you’ll have to get it from Apple Music — you can’t get it from a locally owned record store. For now, you can download Boys Don’t Cry, but it’s very likely that the next Frank Ocean will only be available from whichever streaming service bids the most. Also, good luck finding Ocean’s 2011 mixtape Nostalgia, Ultra — it’s not on Spotify, Apple Music or Tidal, which means many Frank Ocean fans might not even know that it exists.

I look forward to logging into Apple Music tomorrow and hearing Boys Don’t Cry. Ultimately, the most important thing here is having the ability to experience great music. However, I might also feel tempted to buy either a download or a physical copy, while I still can. Not just for old time’s sake, but so that I can be assured that this music will always be there when I need it.