The RX is Uproxx Music’s stamp of approval for the best albums, songs, and music stories throughout the year. Inclusion in this category is the highest distinction we can bestow, and signals the most important music being released throughout the year. The RX is the music you need, right now.

There are certain ways that we determine an artist’s reach or importance: record sales (though possibly not much longer), streaming statistics (though this is helpful for some genres more than others), tour grosses (ditto), and social media follows (strong ditto).

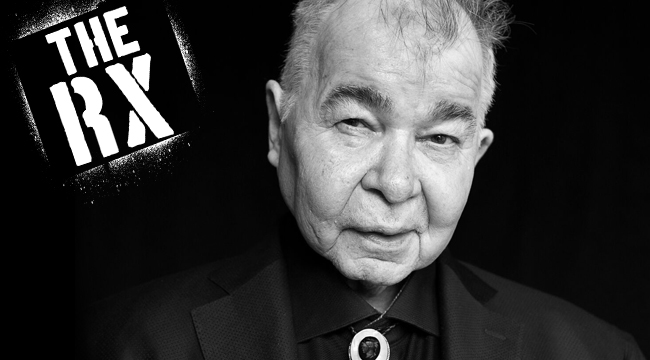

None of this matters when you talk about John Prine.

He’s never sold the most albums or concert tickets, and he’s certainly not a juggernaut in the streaming or social-media worlds. To understand why he has endured for nearly 50 years as one of the most beloved singer-songwriters ever, you have to rely on anecdotal evidence. You must point to actual human beings, rather than numbers, to understand the breadth of his impact. Which makes sense, given that Prine writes songs that sound like real people talking.

Kris Kristofferson (with an assist from Roger Ebert) discovered him. Bob Dylan memorized his songs before his first record came out. Johnny Cash counted him as one of his favorite songwriters. Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, and Steve Goodman hung out with him. Roger Waters borrowed one of his melodies for The Final Cut. Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, and Bonnie Raitt agreed to sing backup for him. And a long list of younger singer-songwriters worship him: Jason Isbell, Justin Vernon, Miranda Lambert, Sturgill Simpson, Kacey Musgraves, Conor Oberst, Jenny Lewis, Kurt Vile, and Jim James of My Morning Jacket, to name just nine.

What people always say about John Prine is that he can say a lot using relatively few words. To love Prine’s songs is to catalog all of the quotable lyrics that describe something small and yet touchingly human. Some personal favorites: The kids who “run around wearing other people’s clothes” in “Sam Stone”; the way Prine changes “I’m sending” to “I’m screaming” in the last chorus of “Clocks And Spoons”; the Hollywood manager who gears up to give his client bad news by “staring at the numbers on the telephone” in “Sabu Visits The Twin Cities Alone”; the brief history lesson about a local Wisconsin legend that begins “Lake Marie.” If you’re a Prine fan, you might have a completely different list.

For such a revered songwriter, Prine hasn’t been particularly busy coming up with new tunes lately. His forthcoming album, The Tree Of Forgiveness, is his first collection of original songs in 13 years. While Prine at 71 maintains an annual tour schedule — in spite of two different cancer scares in the past 20 years — he wasn’t inspired to write and record new material until his wife, Fiona, and son, Jody, encouraged him to get back to it with collaborators both old (like frequent co-writer and guitarist Pat McLaughlin) and new (like Isbell, Amanda Shires, and Dan Auerbach).

For one songwriting session, Prine huddled with McLaughlin and Auerbach and produced six songs in two days — one was the title track for Auerbach’s 2017 LP Waiting On A Song; two were gifted to soul singer Robert Finley, who Auerbach produces; and two landed on The Tree Of Forgiveness, including an apocalyptic blues lament called “Caravan Of Fools,” and a romantic ballad that’s arguably the best track on the record, “Boundless Love.”

When Prine called last week to talk about The Tree Of Forgiveness, he laughed when I mentioned my favorite line from “Boundless Love”:

Sometimes my old heart is like a washing machine

It bounces around ’til my soul comes clean

It’s such a quintessential Prine lyric: funny but touching, colloquial but poetic, seemingly tossed off but actually impeccably crafted.

“I’ve got an interesting little story about that particular line,” Prine said. “I called up Dan and said, ‘Listen, I’m going to change a few things in ‘Boundless Love.’ I’m going to John Prine it up.’ Really, I just needed to make it more like my song than what we wrote. And it was the second verse that you’re talking about. I think part of it was like ‘a wooden crutch talking to a busted tooth,” and that sounded a little bit too Dylanesque for me. So, I changed it to, ‘Sometimes my heart’s like a washing machine, it bounces around ’til my soul comes clean.’ I figured that sounds more like something John Prine would write. This is a new thing for me, to try and be John Prine. At the same time, I am John Prine.”

During our conversation, I tried to find out how exactly John Prine goes about being John Prine.

What have you been up to today?

To start, I signed 200 CDs before breakfast.

Oh man.

I didn’t eat breakfast until noon, but I didn’t get up until 11. I found out real quick for this album cover that I had to use silver Sharpies. Nothing else is going to show up unless I write across the old dude’s face.

I’m really enjoying the album. It’s been a while since you’ve put out a record of original songs. As far as songwriting goes, do you feel warmed up now?

We’ve been really anxious to get the record out on the street. If it’s received as well as I hope it is, I’ll probably be jammed touring for the next few years. We’re usually out on the road anyway, but it will be nicer with a new record out.

I’m not the kind of guy who hangs around in the studio clambering to get the next record out. My family had to trick me into doing this one. My wife is my manager now and my son is running the record company. They pulled me aside last summer and told me it was time for a record, and I believed them.

You actually checked into a hotel to finish off the writing of the songs. Why?

Well, my wife knows I work better in a hotel. After 45 years on the road, I just can conduct myself better in a hotel. I don’t get anything done at the house. I’m not organized. I’ve got an office, but it’s actually just a place I go to hide so it looks like I’m working. I stay out all day and come home around five like a regular person. But basically, I’m just out eating hot dogs and hanging out with friends and shooting a game of pool. I can’t make myself sit down at two o’clock in the afternoon and write a song. It just doesn’t happen like that for me.

There’s a famous story about how you wrote all of those amazing songs on your self-titled debut record, like “Hello In There” and “Sam Stone,” while you were working as a mailman out on your routes. Do you still write songs in your head like that? Like, if you’re at the grocery store, are you thinking about songs the whole time?

When you are delivering mail, there’s not a whole lot to think about. It’s like being in a library with no books. So you’re forced to use your imagination and daydream about whatever you want to. My daydream back then was songwriting. That was my hobby, but I wasn’t thinking about doing it professionally. I had a lot of time on my hands and I was on the mail route, and I wrote some of those earlier songs out there because I didn’t have nothing else to do.

Will I go back to the post office just to write songs? That’s too much to give up for your art.

But you said before that you can’t just sit down and write a song on purpose. So how does that inspiration happen for you?

I’m thinking of one thing while I’m writing about another. Like today, I went out to get the mail and saw a bumblebee, so then I decided to write a song. I’m sitting there thinking about the bumblebee, but the song is moving across that thought. When you’re writing, you’re thinking about form and meter and everything — that’s the skill part — but when you’re trying to actually come up with the part that comes out of nowhere, I can’t think about just that and do that. It doesn’t work that way for some reason.

I think that some people are just wired that way more than others. I know guys living in Nashville — every other person is a writer, you know, or at least calls themselves that — and they almost studied it in school to be a songwriter. But they don’t have the other part, the part that I just stumbled on. They don’t have that part.

Bob Dylan once described your songwriting as “Proustian existentialism.” I’m pretty sure I know what he means — you write about small things in such an evocative way that it hints at larger, more profound truths. But do you feel like that’s an accurate summation of what you do?

You know, I don’t care if it’s accurate or not. Bob Dylan said it. If he were to talk about your song and say it’s the worst thing he ever heard, at least he heard it. But I feel really good about it. I kind of knew Bob Dylan. It’s not like we go bowling together or anything, but he would be listening to my stuff and he would appreciate it. He told me that early on with the first record. And throughout the years, it was really nice to actually get a quote from him that they’ve used over and over again. I didn’t entirely understand the whole quote, but it sounded good to me.

I know he’s talked about “Lake Marie” being a personal favorite of his. Were you surprised he picked that song?

No, not really. I know what he likes, at least in the last 15 or 20 years, as far as subject matter. He’s written stuff about time and jumping through time. I know that’s interesting for him to be talking about, “I was standing here,” and then all of a sudden it’s a different subject, but you’re talking about the same area and everything.

I was happy when I wrote “Lake Marie.” Whatever I was going for, I felt like I got it. I knew I wanted to start out with something that was a little piece of history and then take off from there. Base everything on fact and from then on just take off and tell three different stories and tie together with these two lakes.

It’s a pretty complex song, in terms of the different storylines and the mix of fact and fiction. You usually just write about one small vignette.

I know. And I was surprised it worked in the end. I don’t know if I would attempt it again because I thought it worked really well that time around. I like recitations. I was a big Hank Williams Sr. fan. My dad was, too, and he’d play Hank Williams around the house all the time. And there was a certain amount of Hank Williams’ repertoire, he did it under the name of Luke The Drifter, and they were all recitations. Some of them were religious songs. Most of them were very moralistic. There was some kind of moral to the story and the only thing he would sing would be the choruses.

A lot of people come see me, and sometimes I go on in-between songs with these stories that don’t seem to have anything to do with the song I sing afterward. So I started doing that in the song. I figured I’d talk about what I was thinking, and sometimes it works.

You mentioned that you see Dylan occasionally. You’ve always seemed to get along with your songwriter peers.

When you’re in Nashville, you run into a lot of them. Guy Clark just passed two years ago, and I used to run into Guy all the time. I was out doing my chores, and I’d stop by his house, whether it was just five minutes or a couple of hours, just to stop in and say hello. Especially after he got off the road and couldn’t travel no more. A lot of really good songwriters live here in Nashville. Townes Van Zandt used to live here. There’s a lot of people you run into.

I think the last three times I ever saw Dylan was out in California. I went out there for whatever reason, to do press or I made two records out there with Howie Epstein from the Heartbreakers. That was probably the longest I spent in Hollywood in the last 40 years.

Did you ever feel a sense of competition with those guys, friendly or otherwise?

Not so much. I knew I already had a style that I was writing in, and I was trying to write the best John Prine song I could.

The new record includes a song you co-wrote with Phil Spector, “God Only Knows.” You co-wrote another song with Spector, “If You Don’t Want My Love,” for 1978’s Bruised Orange. Does “God Only Knows” derive from the same period?

Yeah, I went back. It was kind of an accident that I wrote “If You Don’t Want My Love.” The first time I met him, I was at his house. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Robert Hilburn?

Sure. He was the music critic for the Los Angeles Times for decades.

Robert was a big champion of my early stuff. I ran into him in Hollywood and asked him what he was up to, and he was trying to write a biography on Spector. And he asked me if I wanted to go meet him. And I said, “Sure, but he wouldn’t know me if I met him.” And Hilburn said, “Oh no, he was quoting your lyrics the other night.” I go, “Well, that’s really odd that Spector would be quoting my lyrics.”

So, I went to the house and it was a big circus. Two body guards and everybody had a shoulder-holster. He had just finished that Leonard Cohen record [1977’s Death Of A Ladies Man]. There was about four hours of, actually, nonsense. I was enjoying it. I just like the show. I was leaving to go back to my hotel at about one in the morning. Phil was walking me to the door. We walked by a piano and he handed me an electric guitar, and we sat down and wrote “If You Don’t Want My Love” in 30 minutes. And then I went back to Chicago and recorded it about four months later, and the next time I was out in L.A., I thought, “I’ll play this for Spector and see how he likes it.”

And I did, and I was leaving the house that night, we wrote half of a song called “God Only Knows.” I had tried to finish it probably three or four times over the years. I would just put it back up on the shelf and say, “I just don’t feel like finishing it right now.” When I checked into that hotel, I took 10 boxes of unfinished lyrics and about four guitars. And in the middle of all my writing, the Spector song came back out and I saw exactly what it needed. It needed a bridge and another verse, and I wrote it and the thing was complete to me. Showed it to Dave Cobb and he loved it so we cut it.

That’s amazing!

I got an address for Spector. I haven’t heard back from him yet, but we tried to send the record to him so he could hear it. I don’t know if we’ll hear back from him or not. He’s in jail for life. I don’t know if that’s what the sentence was, but he was in his 70s when he got sentenced, so I don’t know if he’ll ever see the outside again.

At this point you could write a song about Phil Spector.

Yeah, I think I’ll wait.

This is sort of a random question, but I’ve always wondered about the cover of your first record. You were born and raised in the Chicago area, and yet on the cover of that album you’re sitting on a bale of hay. Was the record company trying to market you as a “good ol’ boy” southern singer?

I’d gone to Memphis and made my record. Four months later, they fly me to San Francisco to do my album cover, and a pickup truck comes up and a bale of hay arrives. And I said, “What’s that?” And the photographer says the bale of hay goes in the background. That’s what he told me. In other words, it would just be the background behind my head.

Then I saw the cover the day before it hit the stores, and here I am sitting on the bale of hay. And I’d never seen a bale of hay in my life except from a car driving through the country. And I was really pissed off. Then again, I was also really anxious to have a record.

It’s taking me years to live down that record cover, especially with my family. I grew up in the west side of Chicago and here I am on a bale of hay.

You’ve lived in Nashville for almost 40 years now. Do you feel more southern than midwestern now?

I feel like a midwesterner. I always have that in my blood. Mom and Dad was from Kentucky. But the midwestern thing doesn’t leave you. Whenever I get back up to Milwaukee or Chicago, you walk into a burger place and everybody looks like your kind of people.

I wanted to ask you about “Hello In There” because I love it and it’s one of your most iconic songs. I think what really blows people away, among other things, is that you wrote it when you were in your early 20s, and usually when people are that age, they don’t have much empathy for old people. And yet there is so much empathy in that song. What’s your perspective on “Hello In There” now? Do you feel like you did a good job in your early 20s imagining what it would be like to be older?

When I sing it now I don’t think about it. I’m the same person I was when I wrote the song. It’s only when you walk by the mirror that you see how many people you know are in the graveyard. I guess when your knees hurt, too. But I naturally had a lot of empathy for older people when I was a young kid. I was close to my grandparents and I worked a few odd jobs where I had to be around a nursing home. You can see the loneliness with people, and that song poured out of me really easy. I don’t know that I would have written that song as easy today. I’m 71 now. I don’t want to write a song about old people now.

Do you feel more lonesome every day?

Me? No, not at all. I feel like the 23-year-old kid that wrote that song back then.

There’s a song on the new record called “When I Get Heaven.” In the chorus you sing that in the afterlife you’re “gonna get a cocktail / Vodka and Ginger Ale / Yeah, I’m gonna smoke a cigarette / That’s nine miles long.” It’s rollicking and funny, but it’s always a little worrying when someone puts a song about heaven on their album. You’ve had some health scares over the years. How are you feeling now?

Things are going real well. I’ve had cancer twice, and when you go through scares like that, you end up with more doctors, in a good way. When I got my second cancer, the doctor saw that coming down the line. I said, “Just go ahead and cut it out and come back and don’t tell me I have cancer.” And that’s exactly what they did. The doctors, as rotten as my whole body is, they know everything about it, and they can see stuff.

I do have a good story about “When I Get To Heaven.” All I had written was that chorus, about the cocktail and smoking a cigarette nine miles long. I love smoking, and I quit 20 years ago when I got my first cancer. When I see somebody fire up outside a restaurant, I want to go over and stand by them so I can get that first whiff. I miss it that much.

So I wrote this chorus of a song. Before I had the subject matter, the song was like waiting for happy hour. You know, like, “I can’t wait to have my favorite drink at five o’clock, and I might as well have a cigarette that’s nine miles long with it.” And I’m thinking, “Where could I do that?” I can go have the drink, but I’ll never be able to smoke until I get to heaven. I couldn’t have any cancer there, and why would they have “no smoking” signs in heaven? So, that’s why I made the song that way.

I love that this was all an excuse for you to smoke again.

It’s the lengths you’ll go to. Like what you’ll do for love, you know?

John Prine’s The Tree Of Forgiveness is out on April 13 on Oh Boy Records. Order it here.