On Friday, The Cure will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, 15 years after they were originally eligible. That it took so long to recognize the defining goth-pop band of the 20th and 21st centuries proves that not enough Rock Hall voters ever spent time as depressed teenagers in the ’80s, ’90s, or now. But for those of us who have suffered through that particular detail, The Cure is undeniably important.

For anyone who might argue otherwise, it should be known that The Cure invented a new kind of youth music, which you can still hear traces of today. Just like Robert Smith, perpetually alone above a raging sea, dreamt up the effervescent valentine that is “Just Like Heaven,” The Cure is a sleeper cell lurking in the architecture of modern pop, influencing new generations of ponderous, gorgeous songs designed to guide teens through their most epic wallows. Indie, emo, Soundcloud rap, even mainstream pop — all of it has been touched in some way by the influence of The Cure.

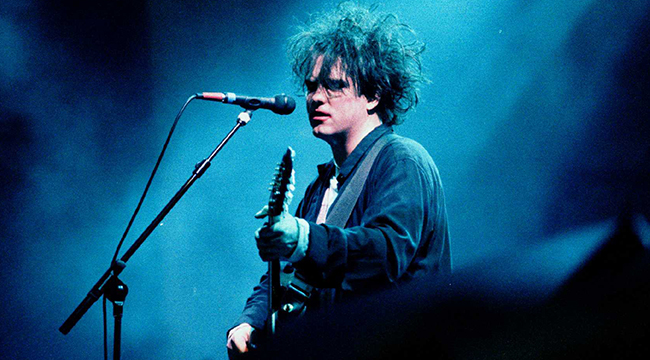

Formed in 1976 and guided for more than 40 years by Robert Smith, the poet laureate of cosmically doomed loner romanticism, The Cure first hit their stride in the early ’80s on mesmerizingly dreary post-punk albums like 1980’s Seventeen Seconds and 1981’s Faith. Then the band evolved into a shockingly canny pop group on early alt-rock landmarks like 1985’s The Head On The Door and 1987’s Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me, and then even more shockingly embraced full on arena rock with their masterpiece, 1989’s Disintegration, the Reagan/Bush era’s answer to Pink Floyd’s The Wall, a sky-high bulwark protecting sensitive outcasts from an uncaring world.

Before The Cure, kids either listened to sweet, mainstream pop that peddled spritely fantasies of puppy dog love, or screamingly bombastic hard rock and metal intended to send parents straight to the neighborhood exorcist. What The Cure did was isolate a neglected demographic who felt too freakish for pop and too smart for metal. Smith perfected a kind of head music for cloudy minds, slowing down the tempos to Black Sabbath-speed, but with guitar riffs that were dreamy and ethereal, evoking a sensation that felt like floating away from your parents, your school, and the overall drudgery of daily existence. The Cure wasn’t alone in pushing this aesthetic during the ’80s, but they were most responsible for mainstreaming it into international suburbia.

Along with giving these kids a soundtrack, The Cure also gave them a look. There wasn’t a high school in the late 20th century that didn’t have a contingent of “Cure kids” decked out in oversized band T-shirts, dark pants, and conspicuous makeup slathered on pale faces. (In The Breakfast Club, Ally Sheedy is a proto-Cure kid.) For the children of Deadheads, Robert Smith was essentially Jerry Garcia meets Edward Scissorhands.

But while The Cure meant the most to outsiders, they could also play to the middle better than almost any of their contemporaries, save for U2 and R.E.M. For about a decade, from the early ’80s to the early ’90s, they truly were one of the most popular and, yes, best alt-rock bands of the time. “Just Like Heaven,” a hymn to hopeless infatuation that remains Smith’s greatest and most emblematic song, became The Cure’s first stateside Top 40 hit in 1987. Incredibly, they had a No. 2 hit single in 1989 with “Lovesong,” a romantic ballad so straight-forward and earnest that Adele eventually recorded a cover and put it on the most popular album of the 2010s, 21. (It’s also been performed by 311, Good Charlotte, Tori Amos, and Death Cab For Cutie — that’s what I call a standard.) And, for a while, The Cure remained hugely popular during the grunge era, with Smith’s Beatleseque charmer “Friday I’m In Love” cracking the Top 20 in 1992.

The Cure started the slow though not entirely disreputable slide into being a nostalgia act by the end of the ’90s. But the influence of The Cure has remained pervasive among artists who cater to alienated 14-year-olds. Billy Corgan (of course) was a Robert Smith acolyte, and Smashing Pumpkins covered “A Night Like This” after alt-rock stations stopped playing the Cure version. (Though alt-rock stations never really stopped playing The Cure altogether.) Once nu-metal swept out grunge, Jonathan Davis of Korn emerged as the latest superstar Cure stan, inviting Robert Smith to perform “In Between Days” on Korn’s MTV Unplugged (!) special. Eventually, nu-metal was replaced by mall punk bands like Fall Out Boy and My Chemical Romance, who also repped for The Cure.

Is it any wonder that in recent years emo-rap stars like the late Lil Peep and Wicca Phase Springs Eternal have sampled Cure songs? What is a face tattoo if not the 21st century version of lipstick and white foundation? But there’s also something sonically prescient about The Cure that points toward the vibe-y, monochromatic “mood” music of pop and rock in the streaming era. In terms of sound and themes, The Cure could be as one note as AC/DC. (For those about to mope, Robert Smith salutes you.) However, this consistency has served albums like Disintegration — which has the high melodrama, profound self-involvement, slowish tempos, and epic length of a typical Drake album — very well.

The Rock Hall, of course, is an imperfect institution for reasons that don’t need to be rehashed here. But, hopefully, this honor will put The Cure in its proper place as a pivotal band in the history of indie and alternative rock. All sorts of weird slights continue to plague this band. For instance, when Pitchfork ranked the 30 best dream pop albums in 2018, it didn’t include anything by The Cure — which is like ranking blues albums and leaving off Robert Johnson. Don’t they know that Robert Smith has literally sung about sleeping for days?

For all of the bumps that Smith gets from each new generation of angsty adolescent bards, his reputation still lags behind that of his most hated rival, Morrissey, and his work with the Smiths. In the critical conversation, there’s an unspoken bias that favors The Queen Is Dead as a “smarter” album than Disintegration, perhaps because it appeals to a slightly older, more collegiate audience. If you ever had a Cure phase as a teenager, you probably saw fit to live down your Cure phase immediately afterward. The Cure is one of those bands that, if you love them, comes to personify the most personal and embarrassing parts of yourself. It’s their greatest curse… and greatest tribute.