The oft-cited, albeit morbid truism about how death inevitably helps the legacies of pop stars usually applies to young artists. Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Nick Drake, Ian Curtis, Kurt Cobain, Tupac Shakur, The Notorious B.I.G., Aaliyah, Lil Peep — we remember them all as eternally vital, effortlessly cool, and imbued with endless, unrealized potential. But in recent years, as some of the most famous icons in modern music have passed on, this same recalibration of public opinion has taken place for those who died in the midst of late-middle age, erasing any lingering ill will and rewriting history to suggest a sustained, uninterrupted period of brilliance.

Consider how, in the final 20 years of his life, Prince was all but exiled from mainstream pop music. While he remained an electrifying live performer, his steady stream of new albums was mostly ignored commercially and dismissed, even reviled, critically. “Another underwhelming entry in his catalog,” Pitchfork sniffed in its 4.7 review of Prince’s 2016 album HITNRUN Phase Two, published just three months before his death.

This was hardly a contrarian opinion at the time. In retrospect, however, I wonder how HITNRUN Phase Two would’ve been received had it come out three months after Prince died. Would listeners recontextualize the music in their minds, hearing it as a final statement by a great artist, rather than a middling misfire by a past-his-prime legacy act? History suggests that they would. But why? What is it about losing our heroes that makes their music sound better?

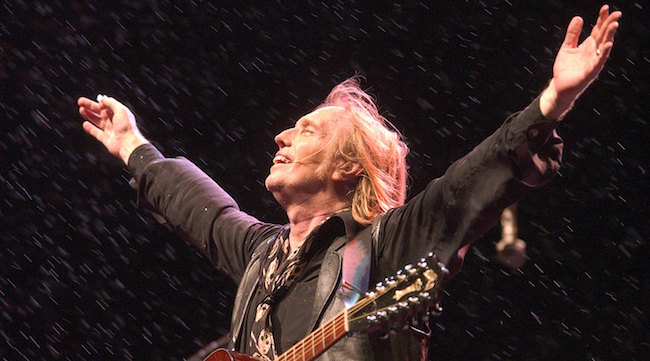

I’ve been thinking about this lately in reference to Tom Petty, who will have been gone for exactly one year on October 2. Ever since he passed, it’s been impossible for me to hear any Tom Petty song and not love it. This is true even of songs I didn’t particularly like when he was alive — if you put on “Rhino Skin,” I’ll ask you to turn it way the hell up. As for the tunes I’d heard a million times and had grown a little sick of, like “Don’t Do Me Like That” or “I Won’t Back Down,” I can listen to them now with fresh ears as I cue them up an additional one million times. My desire to hear Tom Petty songs in the past 12 months has been insatiable. I never get sick of him anymore.

Of course, I don’t totally trust my own opinions here, because I actually wrote my feelings down about Tom Petty right before he died. “Tom Petty could always be counted on to be just good enough,” I argue in my 2018 book, Twilight Of The Gods: A Journey To The End Of Classic Rock. “Recording three or four perfect singles and then padding the rest of the album with jangly, expertly performed filler is just good enough. Rhyming ‘some place to go’ with ‘Joe Piscopo’ is just good enough. Tom did not have to prove it all night. He was fine knocking off at around 11 PM.”

In the book, I compare Petty’s relaxed southern casualness to Bruce Springsteen’s all-consuming desire to achieve greatness at any cost. When I say “Tom Petty could always be counted on to be just good enough,” I meant it as a compliment… though it seems now like a backhanded one. As for the part about how his albums tend to be padded “with jangly, expertly performed filler,” I still think that’s true, though those songs sound less and less like filler to me when I revisit them now. They just seem like, well, great songs.

The hardest thing to accept when Tom Petty died is that I would never get to see him play live again, or hear a new song he had written. This is the case whenever a beloved hero passes away — the conversation between artist and fan suddenly ends, leaving us in an everlasting lurch. Now, the only way I can have a “new” Tom Petty experience is by digging into songs and albums that I didn’t have time for before. It’s what sent me back to records like 1987’s Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough), which I dismissed in the book — it’s the one that starts with “Jammin’ Me,” the source of that immortal “Joe Piscopo” / “no place to go” rhyme — and made me seek out any cool little nooks and crannies I had previously missed. Like “Runaway Trains,” which sounds like a rough draft for The War On Drugs, or the garage-rock rager “Think About Me.” I love those songs now.

Is this just a case of my sentimentality getting in the way of my critical faculties? Maybe, though I don’t think the impact that death has on how we hear music can be attributed solely to nostalgia. It’s also related to the simple economic principle of supply and demand: When you know a product is plentiful, it becomes less valuable. Conversely, when something you love goes away forever, whatever is left behind seems extremely precious.

I’m not the only person who has dealt with the death of Tom Petty by combing through his back pages. Some of his closest confidants — including his daughter, Adria; his wife, Dana; and musical lieutenants Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench from The Heartbreakers — were involved in compiling An American Treasure, due to be issued on Friday as a 26-song “standard edition” and an expanded 60-track box set. Rather than create a definitive overview that covers Petty’s many hits as well as familiar album tracks and a smattering of rarities, in the manner of 1995’s Playback, An American Treasure sticks to the less traveled roads in Petty’s career, spotlighting lesser-known deep cuts along with alternate versions, B-sides, live cuts, and several revelatory unreleased songs.

That means no “American Girl,” no “The Waiting,” no “You Got Lucky,” no “Don’t Come Around Here No More,” no “Runnin’ Down A Dream,” and no “Mary Jane’s Last Dance.” Instead, space is afforded to the lovely “Hard To Find A Friend” from 1994’s Wildflowers, the wistful “No Second Thoughts” from 1978’s You’re Gonna Get It, and the heart-rending “Have Love, Will Travel” from 2002’s The Last DJ.

For Petty, this approach is especially refreshing. Unlike fellow boomer-era heartland rockers like Springsteen and Neil Young, Petty is known in the popular consciousness for a relatively narrow set of hits that were flogged for decades on classic-rock radio and by Petty himself on the road with The Heartbreakers. While Boss fans frequently argue about the merits of Nebraska versus Darkness On The Edge Of Town or Born To Run or The River, Petty’s 1993 Greatest Hits album is by far his most popular record, having sold twice as many copies as the consensus pick for his best studio release, 1989’s Full Moon Fever. While 1979’s Damn The Torpedoes and Wildflowers also have their partisans, Petty by and large isn’t discussed as an album artist. He might be regarded as the quintessential jean-jacketed classic rocker, but he was also an all-time pop star who consistently knocked out radio-conquering earworms from the mid-’70s to the late-’90s, an incredible stretch by any standard.

The level of ubiquity that Petty’s biggest songs achieved had its benefits — there isn’t a Bruce Springsteen tune that’s famous enough to inspire an entire stadium full of football fans to sing-along even when the song isn’t playing. But during Petty’s lifetime, he often seemed hemmed in by the popular staples that everybody knew and loved. Over time, those songs — as wonderful as they are — calcified him into one-dimensional musical comfort food that we could all appreciate without thinking about it all that much.

An American Treasure self-consciously attempts to remedy this, introducing “a landscape of songs a great deal broader than those 20 hits he typically played around America,” as Adria Petty writes in the liner notes. This initially seems to favor hard-core fans like me who already own every album and desperately need new terrain to explore. Like Playback, An American Treasure serves up a number of unearthed delights, like the studio version of the mid-’70s concert favorite “Surrender” and the long overdue release of “Keeping Me Alive,” a delightful country-rocker inexplicably left off of 1982’s Long After Dark. True connoisseurs will also be pleased by the wealth of alternate versions, like an early take on the Full Moon Fever favorite “The Apartment Song” from 1984 with harmonies by Stevie Nicks. I also loved hearing a tougher, more rocking run-through of “Wake Up Time” recorded two years before the bombastic version that appeared on Wildflowers.

The music inevitably turns darker and less bouncy as An American Treasure progresses. By the end of the ’90s, Petty was mired in drug addiction, reeling from a divorce, and witnessing the ongoing deterioration of Heartbreakers bassist Howie Epstein. (He died in 2003 from complications caused by his long-time heroin use.) Publicly, Petty’s laconic cool gave way to barely concealed exhaustion and melancholy — that is, when he felt comfortable enough to be around other people, which wasn’t often. As writer Nicholas Dawidoff notes in an essay packaged in the “super deluxe limited edition” of An American Treasure, Petty was a socially awkward loner who had “tinted windows on his soul,” a side effect of a troubled childhood dominated by an abusive father that haunted him for the rest of his life.

While listening to An American Treasure on repeat this week, I found myself moved the most by Petty’s largely unheralded latter-day music from the ’00s and ’10s, when he allowed the sad, lonely man behind the rock and roll hero to come out in his songs a little more. Sometimes, Petty could slip into a kind of grouchy, old-man bitterness that didn’t suit him — as a product of the ’70s SoCal music scene that represented the front lines of hippie idealism giving way to corporate greed in rock and roll, it’s a little rich that he could produce the sour diatribe “Money Becomes King” in response to American Idol in the early ’00s.

At his best, however, Petty could still produce charming vignettes like “Down South,” a low-key highlight of his last really good album, 2006’s Highway Companion, in which the graying bard muses that he’ll impress women by emulating “Samuel Clemens / wear seersucker and white linens.” This wit belied the deep reservoir of middle-aged sorrow expressed in the stunning “I Don’t Belong,” a serrated jangler left off 1999’s dour Echo and released for the first time on An American Treasure.

No matter the myth-making of the title, An American Treasure admirably takes stock of Petty’s complicated, multifaceted career — from the quasi-punk roots of “Rockin’ Around (With You)” to the grizzled, near-jammy excursions that The Heartbreakers favored more and more in Petty’s final years, tracking him along the crooked, singular path he walked for 40 years. In this way, An American Treasure is also a surprisingly good introduction for neophytes, no matter the dearth of hits. You already know “American Girl” by heart. Now it’s time to meet the flawed, achingly vulnerable man who built all of those national monuments.

An American Treasure is out on September 28 on Reprise Records. Get it here.

Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers are Warner Music artists. .