I truly had no idea what to expect when I flipped on Derek DelGaudio’s In And Of Itself on Hulu. I’d seen it praised up and down social media, with exhortations to drop everything and watch it, often without necessarily saying it was good, and always without explanation of what it actually is. After having watched it, I think I understand. In And Of Itself is fascinating and infuriating. I don’t know quite what it is and I think I might hate it, but I desperately want everyone I know to watch it so that we can scream about it together. Shall we?

(Yes, there will be spoilers in this piece, because that’s what discussion requires, and anyway, can you even “spoil” magic?)

In And Of Itself is a magic show, sort of, and even if Derek DelGaudio doesn’t perform that many tricks in this 90-minute one-man show, the show itself is an act of magic. It has card tricks, impressive ones, but DelGaudio’s central sleight of hand is the illusion of transparency. That magic is not just magic but some form of self-fulfillment. DelGaudio has been described in The New York Times as “the comedian who wants to break magic.” He’s famous, too, sort of. He was a magic consultant on Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige, worked as an assistant to the late Ricky Jay, and has been hailed as a prodigy by everyone from David Blaine to Penn and Teller.

DelGaudio’s latest work, In And Of Itself, directed by Muppet godfather Frank Oz and with music by Mark Mothersbaugh from Devo, combines elements of self-actualization, performative introspection, young millennial navel-gazing, and influencer culture. It’s either a brand new kind of magic or just the same old magic wrapped in nearly impenetrable layers of self-justification.

The show opens pensively. Home videos play as DelGaudio narrates: They ask you, what do you want to be when you grow up?

…Later they ask you, what do you do?

Which is just another way of saying, ‘what have you become?'”

So you search, you look at the roles the world offers you, trying to find the one that reflects you.

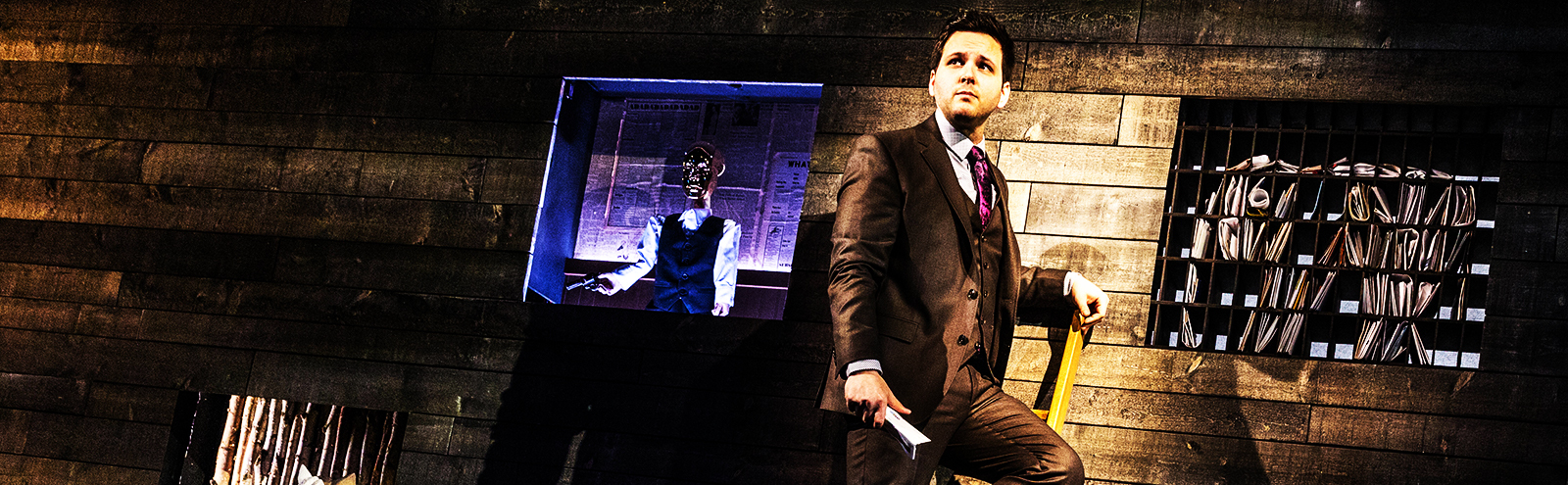

This leads us inside the theater, to a wall on which cards have been placed reading “I AM,” with some kind of “role” underneath — opponent, ophthalmologist, optimist. Sometimes they’re jobs, sometimes personality traits, sometimes puns or states of being. The audience files in, choosing one card for themselves, then quietly wait for the show to begin as a title card tells us that DelGaudio performed this show 552 times in a small theater in New York City. DelGaudio, who looks like a cross between Man Vs. Food‘s Adam Richman and young Seth MacFarlane, takes the stage, opening the show on a pensive note. He solemnly delivers his first anecdote, about a man in a bar in Spain who told DelGaudio that DelGaudio reminded him of someone. That someone was known as “The Rouletista.”

The Rouletista, DelGaudio goes on to explain extremely slowly, was a man who came back from the Great War an alcoholic, who turned to playing Russian Roulette. Without referencing The Deer Hunter, DelGaudio explains that the man played the first night and won, and then did what Russian Roulette players rarely do: he came back for a second night. He came back again and again, as audiences and purses grew and grew, until he added more and more bullets. One bullet. Two bullets. Three bullets. Four. Again and again he won until finally he demanded to play with six bullets. As he put the now fully-loaded revolver to his temple, there was an earthquake that displaced a ceiling beam, knocking the gun out of the man’s hand, at which point he quit the game.

Retiring to a mansion built with the money he made playing roulette, The Rouletista was confronted one day by a burglar. The burglar pointed a gun at The Rouletista, who scoffed at the notion that he could be harmed by guns, whereupon the burglar shot him dead through the heart.

All of this foreshadows DelGaudio’s chosen identity and his basic storytelling style. First of all, why Spain? It doesn’t seem to be important at all, yet DelGaudio includes the apparently throwaway detail, something he will do throughout the show, adding random details to everything in a way that makes us wonder, “Where the hell is he going with all of this?” It’s the central question driving In And Of Itself forward even as the answer, it seems, is ultimately nowhere.

In a show all about identity and self-conception, the central question is why DelGaudio takes being called The Rouletista to be such a painful revelation. Initially, it leads to magic tricks. This will become the pattern of In And Of Itself — DelGaudio doing a confusing 15-minute monologue about knowing one’s self as a lead up to two minutes of very impressive magic tricks.

He tells a story about someone throwing a brick through his window because his mom was a lesbian. Then he makes the brick disappear. He does card tricks — second deals and precise cuts that clearly require hundreds of hours of practice, effortlessly sorting and making people’s cards disappear and reappear in surprising ways. The choose-a-card, any-card trick leads into a similar one, only now the cards are actually letters. DelGaudio brings audience members onstage to open and read the letter they’ve chosen, seemingly at random. The letters turn out to be something heartfelt from someone who loves them. How did he do that??

Like almost all magic, the trick involves making the audience believe that the magician can read minds and predict the future. Unlike all magicians, DelGaudio uses this power not so much to make the crowd “ooh and ahh” but to convince them they are loved, that they are appreciated, that maybe they should reach out to that estranged father or tell their best friend they love them. He’s like Tony Robbins meets David Blaine meets an inspirational quote shared on Instagram. By the end basically the entire audience is crying and it’s hard to say exactly why.

Meanwhile, there are weird celebrity cameos. Hey, isn’t that Kamau Bell in the audience?

In Delgaudio’s closer, he reapplies the card trick again, identifying each audience member by the card they’ve chosen. He looks at them and then, with intense eye contact, reads their card back to them. Truth-teller. Mother. Midnight Toker. The celebrity cameos increase in frequency and weirdness. Deray. Larry Wilmore. Tim Gunn from Project Runway. The performance artist Marina Abramovic. Bill Gates. Being identified as the card they’ve chosen seems to, Rouletista-like, cut everyone to the core. Tim Gunn’s hand is shaking. Another woman bursts into tears after being identified as… an entomologist. I still cannot fathom why this would make a person cry. Finally, I can admit it to the world: I study bugs!

Perfectly capitalizing on a culture of performative empathy, Derek DelGaudio’s greatest trick of all was making his audience feel seen. DelGaudio cries along with them (even though we know he has done this more than 500 times), identifying his own mother and brother in the crowd and at one point tearfully telling the audience that, “I’m not just a rouletista… I’m also a son.”

Just like that, we’re back to The Rouletista thing. Why would one object to this identity? Is DelGaudio the Rouletista because he risks destroying himself in order to please an audience? As he told the Times in the same profile, “I daily suffer from the slings and arrows of being ‘a magician.'”

But what exactly are those slings and arrows? DelGaudio treats them as self-evident when they’re anything but. Hannah Gadsby famously contemplated quitting comedy in her acclaimed Netflix special, Nanette, but in that case Gadsby’s critique of the format was specific and pointed, with a clear explanation of why the act, as popularly conceived, was difficult for her, specifically as a gay woman. DelGaudio, by contrast, gives the impression that he invented an elaborate identity for himself (The Rouletista!) only so that he could chafe against it. It’s an odd thing, using one’s art as a forum to complain about having to do art.

DelGaudio said in 2017, that “the next step, with In And Of Itself, is using magic to express real ideas.”

But what real ideas does In And Of Itself express? That some people are mothers and others are entomologists? That Derek DelGaudio is a reluctant rouletista? It’s paradoxical that to justify magic requires claiming that it’s something else. It’s not just magic, it’s art! It’s self-expression!

Some of DelGaudio’s “grand” illusions have a similarly self-canceling effect. The more people cry and DelGaudio acts as if he’s serving us up some tender part of himself, the more I started to reflexively and retroactively apply banal explanations to his tricks. Oh, he has an assistant feeding him the answers. Oh, the person reading the heartfelt letter was clearly a plant.

In And Of Itself sets out to be not just magic, but an exploration of self. Yet I come to the end knowing very little about Derek DelGaudio, about labels, or about myself. In the end, it is exactly what we thought it was and not what Derek DelGaudio seemingly spent 90 minutes trying to convince us it wasn’t. It’s a trick.

‘Derek DelGaudio’s In And Of Itself’ is is streaming via Hulu. Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.