When was the worst time and place to be alive?

This is an ongoing topic of debate for me, which I think last came up around the time The Witch was released. That one was set in Colonial North America in the 1700s, which struck me as a particularly nightmarish period, perfectly befitting a nightmarish movie. At the time I wrote: an awful time period with some of its most awful people. A bunch of sexless, wool-clad fanatics living in humid, malarial wilderness trying to hack a living from an alien landscape, thinking the devil was hiding in every moldy wheat stalk and lady’s period, and a child might have to be sacrificed to appease the sky wizard — hey, no thanks!

Of course, it’s far from the only contender for the sh*ttiest-time-to-be-alive throne. The Revenant is another work about a time and place I wouldn’t exactly be firing up the Delorean to visit. There’s no shortage of them.

In fact, I was recently reading Colin Woodward’s The Republic of Pirates (yes, I am a man in his 30s who still reads pirate books like a 12-year-old boy, get over it), which painted an especially evocative picture of late 17th-century London, a time so sh*tty it inspired men to think a pirate’s life sounded like a good idea. It was a time of open graves, raining feces, and gangs of feral children you could rent for manual labor.

Life in Wapping and the other poorer districts of London was dirty and dangerous. People often lived 15 or 20 to a room, in cold, dimly lit, and unstable houses. There was no organized trash collection; chamber pots were dumped out of windows, splattering everyone and everything on the streets below. Manure from horses and other livestock piled up on the thoroughfares, as did the corpses of the animals themselves. London’s frequent rains carried away some of the muck, but made the overpowering stench from the churchyards even worse; paupers were buried in mass graves, which remained open until fully occupied. Cold weather brought its own atmospheric hazards, as what little home heating there was came from burning poor-quality coal.

Certainly reminds you of the exchange in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. “Must be a king.” “Why?” “He hasn’t got sh*t all over him.”

Disease was rampant. Eight thousand people moved to London each year, but the influx barely kept up with the mortality rate. Food poisoning and dysentery carried off on average a thousand a year, and more than 8,000 were consumed by fevers and convulsions. Measles and smallpox killed a thousand more, many of them children, most of whom were already ravaged by rickets and intestinal worms. Between a quarter and a third of all babies died in their first year of life, and barely half survived to see age 16.

The streets swarmed with parentless children, some of them orphaned by accidents or disease, others simply abandoned on the church steps by parents who were unable to feed them. Overwhelmed parish officials rented babies out to beggars for use as props for four pence a day and sold hundreds of 5- to 8-year-olds into seven years of slavery for 20 or 30 shillings apiece. These small children were purchased by chimney sweepers, who sent them down the flues to do the actual cleaning, sometimes while fires were still burning below them, cleaning coal dust without masks or protective clothing. These “climbing boys” soon succumbed to lung ailments and blindness or simply fell to their deaths. Church officials put the children they could not sell back out on the street “to beg about in the daytime and at night [to] sleep at doors, and in holes and corners about the streets,” as one witness reported. Large numbers of these hungry, bedraggled urchins roamed the streets together in bands called the Blackguards, so called because they would shine the boots of cavalry men for small change. “From beggary they proceed to theft,” the same Londoner concluded, “and from theft to the gallows.”

Oh, and hey, speaking of gallows…

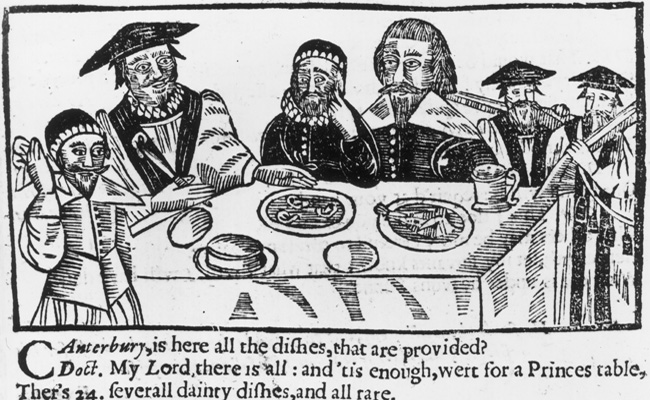

In those days, nobody missed an execution: It was one of the most popular forms of entertainment.

The fun started days or weeks ahead of time at Marshalsea or Newgate Prison, where visitors tipped the guards for a chance to gawk at the condemned. On the day of execution, thousands lined the streets along the route to Wapping, waiting for the prisoners to roll by, lashed inside carts and escorted by guards and the Admiralty marshal. So many people tried to get a glimpse of the prisoners that the three-mile trip often took as long as two hours. By the time the procession reached Execution Dock, festive crowds massed on the riverbank and wharves, choking Wapping Stairs and spreading out on the stinking mud exposed at low tide. The gallows stood out in the mud, and behind them hundreds of passenger boats jockeyed for the best view of the impending event. [source again, in case you missed it the first time]

Really puts the whole Donald-Trump-possibly-being-president thing into perspective, doesn’t it?

Got any suggestions for crappiest time to be alive? Feel free to include your excerpts below and/or send them to me.

Vince Mancini is a writer, comedian, and podcaster. A graduate of Columbia’s non-fiction MFA program, his work has appeared on FilmDrunk, the UPROXX network, the Portland Mercury, the East Bay Express, and all over his mom’s refrigerator. Fan FilmDrunk on Facebook, find the latest movie reviews here.