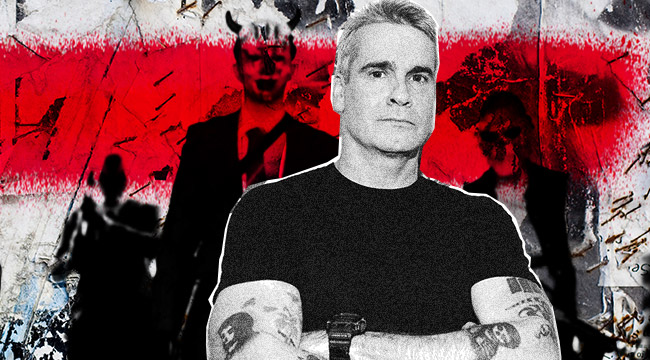

Who Henry Rollins is to you probably depends on how you first discovered him. Front man of Black Flag? The guy from that “Liar” video? The aggro cop from The Chase? Punk shouter, actor, writer, spoken-word artist — Rollins is the prototypical multi-hyphenate, with as many career incarnations as he has current projects. He was never great at being just one thing, and these days, more than anything else, he seems to have become a guy whose opinions people care about. In addition to his occasional acting work, Rollins tours the world doing spoken word. The lead singer who didn’t really need to sing to front a band no longer even needs to write songs to sell out venues.

Believe me when I say that I’m not a person to throw around the phrase “modern-day philosopher,” but what else do you call a guy people pay to hear talk, who they don’t expect to teach, preach, sing, or tell jokes? If not a professional thinker, he has made it as a professional monologist.

Most recently, and the reason he was doing interviews, Rollins stars in The Last Heist, which may have the world’s greatest elevator pitch: “A bank heist descends into violent chaos when one of the hostages turns out to be a serial killer.”

Eat your heart out, Donald Kaufman.

The film hits theaters, VOD, and iTunes this Friday, and the press tour meant I got 10 minutes on the phone with Henry Rollins. Henry Rollins is a guy I’ve wanted to talk to for a long time who I could listen to expound at length on virtually any subject. Punk? Politics? His neck exercise regimen? (Don’t act like you never wondered). But what do you ask Henry Rollins about when you only have 10 minutes?

There’d be far too much ground to cover regardless of which direction I went, so I just chose his most recent L.A. Weekly column at that point, which happened to be his piece about North Carolina’s bathroom law. He had some interesting thoughts on that, naturally, but even in 10 minutes of talking to him, I think I discovered a truism about Henry Rollins. There’s an old, possibly apocryphal Joe Dimaggio quote. When asked, in the late days of his career, why he still plays as hard as he did when he was a rookie — talk about a softball question, but whatever — he replied, “There might be a kid in the stands who has never seen me play.”

Likewise, Rollins strikes me as a guy who, whatever he happens to be doing that day, wants to make sure everyone he comes into contact with gets the full Rollins experience. He will go to what I would consider borderline insane lengths not to feel like he’s shortchanged a paying customer. He seems to be the kind of guy who believes that anything worth doing is worth doing the shit out of. The kind of guy who, above all else, gets things done. Hell, just the mention of his name makes me want to start a to-do list.

I saw your piece about the transgender restroom law in North Carolina. I guess my question is, how do you fight back against a fake problem? Is this our new paradigm, debating fake wedge issues?

I think all you can do is vote. What are you going to do, bash someone over the head? As an artist-type, I could boycott the beautiful state of North Carolina, but I guarantee you that people who would be showing up for my North Carolina show later this year, probably dislike HB2 just as much as I do. I’d be punishing the wrong people by boycotting. So I think ultimately, all the North Carolinians can do is not fall for the bigotry and vote. You still might not get what you want when you vote, as has happened to me many times, but I think that’s the answer.

Right.

If you’re a parent, don’t let your kid end up a bigot. Past that, it’s hard to, anybody who’s in favor of HB2… There is no logic or line of reasoning that you can flex upon that person to make them go, “Oh you know what? Yeah, you’re right.” That’s just not ever going to happen. You just get along as best you can.

It seems like one of those things where they put it out there to distract people from getting anything done, but at the same time, it hurts actual people. Can you find a balance there between trying to focus on things that we can actually get done but also having to fight back against sh*tty distractions?

I think when you really focus on getting things done that would benefit the many, that smacks too much of equality for a lot of state governmental delivery systems to handle. It’s quite obvious to me that America’s not interested in equality, and that we shall not overcome. That’s not going to happen, because it’s not that big a deal to not hate a gay person for his or her orientation. It’s not that big a leap morally, intellectually, or any other way to not be prejudicial against a person who looks ethnically different than you. This isn’t really a hard thing to do. Many millions of Americans choose to be bigoted in whatever thing they’re hating upon. I think that with HB2, using that as an example, it’s just another way to not be equal.

In 1964 the law signed in by Johnson [the Civil Rights Act of 1964], half of the country said, “Oh, no no no no.” Johnson signed it anyway. So, this country is not overwhelmingly interested in progress. Otherwise, you’d have solar panels on your roof.

The older money speaks. And when Sheldon Adelson had as much cover time on a newspaper as your Republican and Democratic front-runner, it just really shows you where America is at. I am not in favor of how it goes, but I’m one person with one vote. I don’t overestimate my power.

Do you feel optimistic about your vote this election?

No. It’s one vote, and it’s the only one I’ve ever struck. It’s mine, and it’s one — obviously, I’m not cheating. I’m never optimistic. If I ever have any optimism, it’s so covered in layers of steel. It deflects bullets and insults and death threats, which I get. My optimism is that I know that I’ll be fine.

I don’t know how it’s going to work out for you though. I’m not saying that in a mean or challenging way. If you were hungry, and I had a sandwich, you can have at least half of it. I don’t know how a lot of people are going to get along in this country in this century. I know for a fact I’ll be fine.

I saw you were doing another spoken word tour earlier this year. How did you get into doing that? Do you correct people if they call it “stand-up”?

I don’t work in the stand-up paradigm in that not everything I say is funny. I don’t exactly resist the title, I just don’t really acknowledge spoken word or anything, I just call them talking shows, and I get up there and talk. I started do those shows in 1983. There’s a local promoter in Los Angeles who would put on these marvelous shows with two hours and 20 people getting on stage… The bass player of Black Flag, the guitar player of The Minutemen, Jeffrey Lee Pierce of The Gun Club, a couple of local poets and everybody got five or seven minutes. It was great. Even when it wasn’t, it was fun. You holler, and it was friendly. I would go because Chuck Dukowski of Black Flag would be on the bill. That was him. Get in the van, go to the big city, and see the pretty people.

One night the promoter said, “Well, I’m doing a show next week, why how about you get up there for seven minutes?” And I said, “I don’t have anything.” He goes, “You’ve got a big mouth, try it. I’m paying ten bucks a person.” I go, “Well I’ll take that money. I’ll take that money off you right now.” So, I went onstage the week after. I had a few things written in my back pocket — a story about what had happened at band practice two days before when our guitar player was nearly killed.

Afterward, everyone asked, “When is your next show?” I said,”There is no next show. I just got this ten dollar bill in my hand.” I started doing more shows immediately. I felt very natural at it.

By ’85 I was doing shows across America, by ’86 I was in Europe, and by ’89 I was doing shows in Australia, Europe, America, Canada. Now, the tour goes to well over 20 countries.

I saw in an interview you were talking about practicing for them out loud, and while you’re walking around. How do you do that without driving yourself crazy?

Because I’m interested in getting it right. I don’t want to fail the audiences. I have a great fidelity to these people, and I like working through ideas in a simple, fundamental way. I think you really can get it done, so that’s how I prepare for those things. In the San Fernando Valley, which is over the hill from where I live, there’s stretches of sidewalk where at 8 p.m. a whole mile kind of rolls up by eight. It all closes. The only thing that’s open is a gas station, and the only people on the sidewalk are dog walkers and joggers. I just walk and talk to myself. People think I’m either nuts or on a cellphone. No one cares. They’re all wearing earplugs or something anyway.

I will walk a mile in each direction, talking through these stories. Hearing my voice say them, and hearing what works and what doesn’t work. I will not do a warm-up show. That means someone else gets a cut of the show, but the next guy, they get the show. I can’t do that, so I arrive on stage fully formed. It’s not to say the stories don’t evolve after a few nights, but I can’t go onstage and give you a mediocre show because of lack of preparation. I should lose a finger for doing that to any audience. Whether there’s 30 people in the crowd or thousands.

With all of these opportunities that you have with spoken word and writing and everything, what is it about a particular movie project that makes you agree to take an acting job?

Usually I get the offer and I’m greedy for work. I like to do things. If the project is repellent — I get a lot of offers that I can’t do. I look at it, and I’m like, “No, I can’t do it.” If it looks like I can do it, or I can be an asset to the production, and I don’t have to throw up in my own mouth to be in it, then I say, “Yes,” and I’m grateful for it. I’m not that picky. I don’t like to be on the couch, so I’ve been in things that aren’t exactly A Streetcar Named Desire, but I’m not exactly Brando, so it’s usually a fit.

A film like He Never Died or The Last Heist — I just felt I could be interesting in the film… I did The Last Heist, the one that will be in the press for today. It’s not a reinvention of the wheel; it’s a genre-specific, tough guy film with blood and a bad guy, and I thought I could do a good scary bad guy in that with that script. I kind of invented the character. I flexed it in front of Mike Mendez, our wonderful director, and he said, “Yeah, that’s really great. Let’s go.” And we went forth.

I basically go in it if I can be an asset, and if I can throw myself into it wholeheartedly. If I can’t be sincere, I can’t show up to do anything.

—

Vince Mancini is a writer, comedian, and podcaster. A graduate of Columbia’s non-fiction MFA program, his work has appeared on FilmDrunk, the UPROXX network, the Portland Mercury, the East Bay Express, and all over his mom’s refrigerator. Fan FilmDrunk on Facebook, find the latest movie reviews here.