Music + Culture

SHOWS

Covers Books

EVENTS

FEATURED

BRANDS

TRAVEL,

DRINKS & EATS

DRINKS & EATS

Latest

Kenia Os Is Pushing Latin Pop Towards A Fierce Future

Kenia Os is very much a pop star of the times. In the past few years, the former influencer parlayed her massive social media following into a music career and a Latin Grammy nomination. Like a true pop princess, Os has also undergone several evolutions in both image and sound with each new album. Now, the Mexican superstar is ushering in her edgiest era yet with her new single "Belladona." "I feel like a completely different Kenia," Os says. "This is the era that I've most liked of my whole career. I've had the most fun working on the music…

Fred Again.. Taps Young Thug For The Uplifting ‘Scared,’ His First New Song Of 2026

It's only been a few weeks since we've had a new Fred Again.. song, but given his ceaseless release schedule in the latter half of 2025, that feels like a long time. Fred unloaded a batch of USB002 songs to round out the year, but now he's back with his first new song of 2026. The track is "Scared" and the collaborator this time around is Young Thug. Like is often the case with Fred songs, the vocal was pre-existing. Here, Thug's vocals are pulled from an unreleased song that fans have referred to as "Lucky." In a recent post,…

Chalk Teeth Make A Striking Debut With Their Brooding Dark Wave Single ‘Struck’

Chalk Teeth have been busy. The trio of Karolina Wallace (vocals and guitar), Adam Wallace (guitar), and Jason Miller (bass, synths, drums, production, engineering) spent much of 2025 performing across Los Angeles and New York. Now, they're preparing a new album, their first, set for early 2026. One of the songs that's been a setlist staple (here's a live clip from 2024) is "Struck," so Chalk Teeth are finally releasing it as their debut single today (January 23). The near-six-minute track falls right in line with how the band describes themselves: "Shoegaze-tinged, motorik dark wave. Black glass synths, washed in…

Harry Styles’ Long-Awaited New Single, ‘Aperture,’ Has Arrived

Harry Styles has kept largely out of the public eye since releasing his 2022 album Harry's House and touring in support of it. Finally, though, he has started to re-emerge. Last week, he announced Kiss All The Time. Disco, Occasionally., a new album, and now, he has shared the lead single, the slow-burning "Aperture." In a SiriusXM interview with John Mayer, Mayer asked about the song's five-plus-minute length and Styles said: "I actually think what I really like about the song is that it was really just about being true to the song. I think when we were in the…

Uproxx’s Jeremy Hecht Explains How Jadakiss And Zohran Mamdani Made New York City History

Zohran Mamdani's inauguration as mayor of New York City was historic for multiple reasons: He's the youngest mayor in NYC history and the first Muslim mayor the city has ever had. As Uproxx's Jeremy Hecht points out, he's also the first mayor to reference a member of The Lox during his inauguration speech. https://www.instagram.com/p/DTD4PGhklC3/ Mamdani said: "And throughout it all, 'We will' -- in the words of Jason Terrence Phillips, better known as Jadakiss or 'Ja' to the mwah' -- 'be outside.'" Jeremy notes, "This referenced an iconic moment during Jadakiss' Verzuz battle where he got on stage and said…

Uproxx’s Baylee Lefton Walks Through Generations Of Women’s R&B And Soul With Her Latest Playlist

Keeping up with music news and resources like Spotify's giant and regularly updated New Music Friday playlist are great ways to keep your listening habits from getting stale. Sometimes, though, you need a deeper dive. That's where Uproxx's Baylee Lefton comes in as she routinely offers quick-hit lists of songs you need to add into your rotation this week. She just delivered a fresh mix and it pays homage to years of standout women making R&B and soul music. https://www.instagram.com/p/DT0nau5AcGD/ Beylee had the impossible task of sorting through decades (starting in the 1960s) of music and choosing just a song…

Enter To Win A $25 Apple Gift Card By Participating In The UPROXX Music Trends Report

Music is one of the fastest-moving parts of the entertainment landscape. Generative artificial intelligence has introduced new possibilities and concerns essentially overnight. Social media platforms like TikTok can create new stars or revive public consciousness of classic icons. More and more each day, musicians are expanding the scope of their creative endeavors beyond music, turning themselves into multimedia forces. Through it all, UPROXX remains dedicated to being at the forefront of innovation and what's next in music and related fields. But, we can't do it alone. That's where you come in, and you could win a sweet prize for your…

Uproxx’s Joypocalypse Dives Into The Mudhoney Album That Inspired Kurt Cobain

Short-lived '80s band Green River were pioneers, commonly cited as offering some of the earliest examples of grunge. When the group dissolved a few years after its founding, some of the members went on to form Mudhoney, who continued the development of grunge as a genre. Their debut release, the 1988 EP (sometimes called an album) Superfuzz Bigmuff, was a pivotal and formative work in the space. As Uproxx's Joypocalypse notes, the project was incredibly influential and even found a fan in Kurt Cobain. https://www.instagram.com/p/DTtUAKfEqD-/ She says: "From one great band to another: After Green River dissolved, we got Mudhoney,…

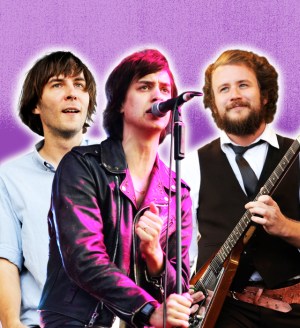

The Best Indie Albums Of 2006, Ranked

This column is about the best indie albums of 2006. By which I mean, my favorite indie albums of 2006. The personal preference is implied, perhaps, but there are biases that have influenced the creation of the following list that must be disclosed before you read another word. I state the following in the spirit of fair play and transparency, so that the reader is equipped with the necessary information to properly assess my assessments. So that when a person reads this and says, "Whoever wrote this is an idiot," they will do so with the assurance of having all…

Gale Follows Her Breakout 2025 With ‘Me Tiene,’ A Lively And Celebratory New Single

Gale had a massive 2025. She released a new album, Lo Que Puede Pasar, which she previously described as "a very honest album about daring to live every experience with your heart without overthinking what might happen." She also co-wrote the CA7RIEL and Paco Amoroso collaboration "#Tetas," winning her first Latin Grammy Award (Best Alternative Song) for her work on the hit. The Puerto Rican singer-songwriter's 2026 is already going well so far, as she recently released "Me Tiene," her first new song of the year. The single is playful and immediately full of electro energy. In a statement, Gale…

Sombr, Alex Warren, And More Will Join Sabrina Carpenter On The 2026 Grammys Performance Lineup

Earlier this week, we got our first taste of what the performances will look like at the 2026 Grammys, as Sabrina Carpenter was revealed as the first artist on the performance roster. Now we know more, as today (January 21), the Recording Academy announced that all of this year's Best New Artist nominees -- Addison Rae, Alex Warren, Katseye, Leon Thomas, Lola Young, The Marías, Olivia Dean, and Sombr -- will perform as part of "a special Best New Artist segment." Of the Best New Artist nominees, a few of them also earned consideration in other categories: Katseye's "Gabriela" is…

ASAP Rocky Is Taking ‘Don’t Be Dumb’ Around The World On A Huge 2026 Tour

It took years, but ASAP Rocky's new album Don't Be Dumb is finally here. Furthermore, fans will soon be able to hear the project on the road, as Rocky just announced a massive world tour set to run from May to September. It starts with a North American leg, which features stops at venues like the Chicago's United Center, Los Angeles' Kia Forum, Toronto's Scotiabank Arena, and Houston's Toyota Center. A UK and European run follows starting in August. The general on-sale for tickets starts January 27 at 9 a.m. local time. More information about that and about the various…

Young Miko Is Riding The Wave Into A Flow State

After an exciting past year, Puerto Rican rapper Young Miko is in homebody mode. Home in Puerto Rico, Miko -- whose real name is María Victoria Ramírez de Arellano -- abides by a consistent schedule. Mornings are reserved for press and promotions, and afternoons for high-intensity interval training in preparation for touring. At the time of our conversation, she is sitting at home with her one-year-old dachshund Naila in her lap. Though her second album, Do Not Disturb, dropped only two months ago, she may pop into the studio later that day. "I'm always in the studio, to be honest,"…

The E1 Series Showcases The Key Ways Spirits Align With Sports

It's not uncommon these days to see alcohol brands sponsoring sporting events. In fact, the two go hand in hand. Whether it's Hennessy as the NBA's global spirits partner or Budweiser at the Super Bowl, drinks brands have long known that, though the athletes might be dry, working alongside sports leagues to ensure their spectators are taken care of is a key piece of the experience. Surely, anyone who's been tailgating at a football game can tell you how much better the experience is with great drinks in your glass (or red plastic cup). The rise of the UIM E1…

Zach Bryan Lands His Second No. 1 Album As ‘With Heaven On Top’ Has A Major Debut Week

Zach Bryan is one of the biggest crossover country artists of the past few years. His 2023 self-titled album topped the Billboard 200 chart and its follow-up, 2024's The Great American Bar Scene, bowed at No. 2. Now, Bryan is back on top: On the chart dated January 24, Bryan's new album With Heaven On Top debuts at No. 1. It dethrones Morgan Wallen's I'm The Problem, which slips to No. 2. Meanwhile, The Kid Laroi also had a big debut, with Before I Forget debuting at No. 6. Bryan recently wrote of the album: "'With Heaven on Top' is…

‘The Beauty’: Everything To Know About Ryan Murphy’s New FX Series With Evan Peters And Ashton Kutcher

Ryan Murphy is busy. Over a ten-day stretch in 2024, for example, he released four new shows: American Sports Story: Aaron Hernandez, Grotesquerie, Monsters: The Lyle And Erik Menendez Story, and Doctor Odyssey. In 2025, he was also involved in Mid-Century Modern, All's Fair, and 9-1-1: Nashville. He'll have a big 2026, too. Set to drop soon is The Beauty, a new FX series that, in his words, takes on "Ozempic culture." The show is based on a comic book series by Jeremy Haun and Jason A. Hurley. Ahead of the show's release, keep reading for everything you need to…

Uproxx’s Joypocalypse Breaks Down How Soundgarden’s Slow-Burning Grooves Make Them Distinct

Just a few months ago, Soundgarden achieved one of the highest honors in all of music with their induction into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. It all started in the '80s when Chris Cornell, Kim Thayil, and Hiro Yamamoto formed the band. There would be a handful of personnel changes, but in a few years, the group settled into its classic lineup of Cornell, Thayil, Ben Shepherd, and Matt Cameron. They became stars with the release of 1994's Superunknown, which features the group's signature song, "Black Hole Sun." After disbanding in 1997, they reformed in 2010, but called…

ASAP Rocky All But Confirms One Of His ‘Don’t Be Dumb’ Songs Disses Drake

At long last, after years of teasing and delays, ASAP Rocky has dropped his new album, Don't Be Dumb. Quickly, a standout track is "Stole Ya Flow," due to lyrics that seem to be dissing Drake. Relevant lyrics include, "First you stole my flow, so I stole yo' b*tch," in reference to Drake's rumored fling with Rocky's now-partner Rihanna, as well as, "n****s gettin' BBLs, lucky we don't body shame," a nod to Drake's supposed enhancement surgeries. Later, he references his former friendship with Drake and the rapper's son, saying, "First you was my bro, p*ssy n**** switched / Turned…

Mitski Follows A Standout 2025 By Announcing A New Album And Sharing The Single ‘Where’s My Phone?’

A few months ago, Mitski shared a terrific concert film. At the end of it, she teased a new album, indicating it was set for "the winter." Well, now we know more about that, as Mitski just announced Nothing's About To Happen To Me is set for February 27 via Dead Oceans. Today (January 16), she also shared a new single, "Where's My Phone," and an accompanying video. The song is a fuzzed-out rocker, and in the video, Mitski plays a recluse in a house full of clutter. Mitski hasn't given many interviews lately, but she did have a chat…

Days Before Release, ASAP Rocky Reveals The ‘Don’t Be Dumb’ Features And Tracklist

At last, Don't Be Dumb is finally coming: ASAP Rocky's long-awaited album is set to drop tomorrow, January 16. As the days remaining turn into hours, Rocky has pulled back the curtain by revealing the tracklist. He also shared the list of features (but not who appears on what track). The lineup is an eclectic mix, featuring Tyler, The Creator; Westside Gunn; Doechii; Brent Faiyaz; Thundercat; Gorillaz; BossMan Dlow; will.i.am; Danny Elfman; Jon Batiste; Slay Squad, and Jessica Pratt. Meanwhile, in a recent interview, Rocky spoke about how his mother wanted him to start a relationship with Rihanna, saying, "My…

Harry Styles Finally Announces His First Album In Four Years, ‘Kiss All The Time. Disco, Occasionally.’

Harry Styles has been at at a wedding in Paris, the Vatican, and Japan lately, among other places. Those "other places" apparently include the studio: Today (January 15), Styles announced a new album, Kiss All The Time. Disco, Occasionally.. The project is set to drop on March 6. The only other info we have about it at the moment is that it has 12 tracks and was produced by Kid Harpoon. Styles shared the cover art as well. The last the public saw of Styles in a major way was on the Love On Tour that ended in 2023. When…

The BTS Comeback Ramps Up As The Group Reveals The Title And Release Date Of Their New Album

BTS have been gradually rolling out their return this month. First, they teased an album and a tour. Then, they announced the tour dates. Now, it's album time, as today (January 15), the group announced Arirang, which is set for March 20. BigHit's website says of the album: "BTS The 5th Album, 'ARIRANG' holds special significance as it marks the first album released by the group in three years and nine months and sets out the the direction the members will take moving forward. The members were deeply involved throughout the songwriting and production process, infusing their own thoughts and…

Gracie Abrams Is Set To Make Her Acting Debut In A New A24 Movie

Gracie Abrams has Hollywood in her blood, as her dad is J.J. Abrams, one of the most acclaimed and successful filmmakers of the past few decades. Gracie herself hasn't gotten into acting in a major way, though... until now. Per The Hollywood Reporter, Abrams will make her acting debut in Please, a new A24 movie from Babygirl director Halina Reijn. Not much is known about the film, but The Hollywood Reporter notes that per sources, it's "a period female drama and will be a continuation of the edgy romance genre that Reijn tackled with Babygirl." In an Elle interview from…

Blackpink’s Long-Awaited Comeback Project Has A New Release Date And It’s Soon

Last summer, YG Entertainment founder Yang Hyun Suk said that Blackpink were shooting to have a new project out by the end of the year. He said at the time, "A lot of fans are curious about Blackpink’s album. I know that the Blackpink members and producers in charge of them are working very hard preparing the album. I’m hoping for Blackpink’s album to be out by November, at the latest. That’s what I’m pushing for – we’ll do our best to get Blackpink’s album out soon.” Well, they tried, but ultimately, it wasn't out by November, or the end…

Rolling Loud Is Doing Just One US Festival This Year, Led By Playboi Carti, Don Toliver, And NBA YoungBoy

Last week, Rolling Loud made a big announcement: They're doing just one US festival this year, and it's going down at Orlando's Camping World Stadium from May 8 to 10. Now, the other shoe has dropped, as today (January 14), they revealed the lineup. Headlining are Don Toliver, Playboi Carti, and NBA YoungBoy. Also playing are Chief Keef, Destroy Lonely, Sexyy Red, EsDeeKid, FakeMink, Nettspend, BossMan Dlow, OsamaSon, Homixide Gang, PlaqueBoyMax, SkaiWater, TiaCorine, Lazer Dim 700, and others. Tickets are available now on the festival website. In a statement, Rolling Loud co-founder Matt Zingler says: "Rolling Loud 2026 represents a…

Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea Announces His Debut Solo Album With A Thom Yorke Collaboration

While Flea is best known for his decades with Red Hot Chili Peppers, he routinely keeps himself busy outside of the band. Sometimes it's with acting, sometimes it's with supergroups like Atoms For Peace. It may be surprising, then, that he never released a solo album... but that's about to change soon. Today (January 14), Flea announced Honora, his first-ever solo album. It's set to drop on March 27 and it focuses on jazz and Flea's trumpet. He was joined by a venerable crew of jazz musicians: producer and saxophonist Josh Johnson, guitarist Jeff Parker, bassist Anna Butterss, and drummer…