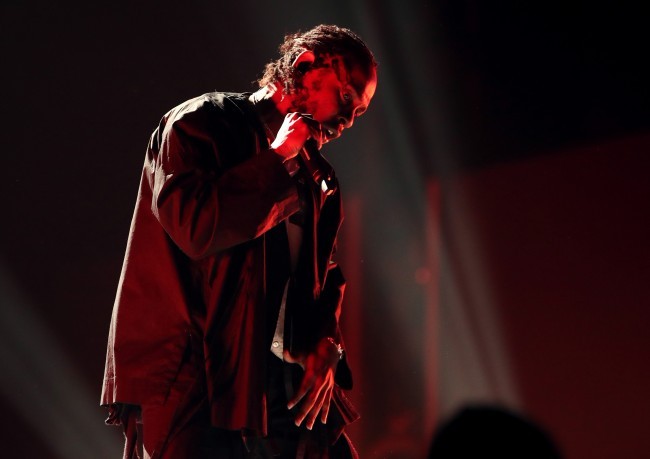

By now, you’ve surely read or heard on TV or around the water cooler that Bruno Mars’ 24K Magic won the Album Of The Year Grammy, beating contenders like Jay-Z, Kendrick Lamar, and Lorde. You may have even heard that there’s been a pretty significant backlash to the pick; even Bon Iver, who had no dog in the fight, chimed in on the upset, questioning how Mars’ admittedly excellent 24K could deserve to win over Jay’s deeply personal 4:44 or Kendrick’s transcendent DAMN. Digital ink is even now being spilled to decry the Grammys’ atrocious record in terms of honoring women and other minorities with awards.

You might be wondering, even now, What’s the big deal? Isn’t Bruno Mars an ethnic minority himself? You people are never satisfied. Well, I’m glad you bring the point up because it seems like you’ve hit upon The Recording Academy’s rationale in selecting Bruno over other worthy options and their inevitable defense when taken to task by just about the entire music industry over it in the months to come.

Because here’s the thing: Bruno Mars is not your loophole, Grammy committee.

I can see the thinking behind the selection. Bruno, born Peter Gene Hernandez in Honolulu, Hawaii, is Filipino and Puerto Rican, and his album was a pastiche of Black musical sounds from the past three decades, incorporating old-school hip-hop and New Jack swing, funk, R&B, and trap-rap beats to pay homage to the songwriters and singers Bruno looked up to as a youth. 24K Magic is wall-to-wall bops, a collection of undeniable toe-tappers and bedroom mixtape anthems.

However, the selection rings hollow when you consider the recording industry’s overall history of only acknowledging Black music divorced from Black faces. Elvis Presley is the “King Of Rock And Roll” for lightly editing a blues number originally performed by a Black woman, Big Mama Thornton, and playing a musical style pioneered by Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Eminem has won Rap Album Of The Year every show he’s been nominated but one (for Encore), and somehow, Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’ The Heist lived up to its title against Kendrick Lamar’s Good Kid, MAAD City, a selection so egregious even Macklemore himself had to acknowledge that Kendrick was robbed.

Once again, it seems Black music could only win the most prestigious award of the evening transplanted into a lighter, more acceptable presenter. It’d be fascinating if weren’t so damned frustrating. The rationalizations and mental gymnastics that Grammy voters put themselves through to make that one happen must have been truly astonishing. The problem is, no matter the process, the product is the same. The Grammys have sent the same message that they’ve gone out of their way to send practically since their inception: You aren’t good enough.

Why does it matter, though? Who cares what a bunch of stodgy, old, white guys think? After all, part of the fun of watching the show is the hilarious borderline ineptitude in their nominations and presentations of genre categories they either don’t understand or can only poorly define (“Urban Contemporary,” anyone?).

When it comes to institutional racism — because that’s exactly what this is — everything is interlinked. A system of hierarchy of human value rooted in a skin color — that defines Black people (and other ethnic minorities) as inferior — must reinforce that inferiority in every avenue, from education to employment to housing to the arts. It ensures that their cultural contributions are ignored or belittled, no matter how well-liked they are or how objectively popular they are (DAMN. debuted at No. 1 on Billboard‘s album chart, while each of its 14 songs charted on the Hot 100 singles chart).

The Grammys need to honor the growing cultural diversity of music and the music audience by changing their message. They need to demonstrate that they truly believe that minorities are just as good, that they can compete on an even playing field, that their contributions are worthwhile and needed. By setting Black and other minority artists on equal footing and validating their efforts, it necessitates the same validation in those other, linked areas. It changes the perception, ever so slightly, to allow for achievement outside of music and the arts.

This is why progressive folks pitch a fit when a Filipino performer in New Jack cosplay wins Album Of The Year. No matter how well he performs, the Black performers creating Black art are right there. Why should we settle for a proxy, a pastiche, when the genuine article was also nominated? Furthermore, considering how personal Jay and Kendrick’s albums were, addressing everything from their relationships to mental health to their faith, the insult cuts twice as deeply. It’s not just a rejection of their art, it’s a rejection of them.

The continuation of a pattern that has been called out, again and again, only pours salt in the wound. It’s a slap in the face to an increasingly diverse audience, an audience that has continuously seen validation dangled over their heads, only to be pulled out of reach again at the next awards show, on the next admissions exam, at the next election. For every two steps our beautiful, diverse, flawed, nation takes toward true equality, it seems to take one-and-a-half back, and nights like the 2018 Grammys are only reminders of that.

So, congratulations to Bruno Mars. You earned it, and you should feel proud of the hard work you put into 24K Magic. But, Grammy committee, don’t think that this lets you off the hook. You’ve done a disservice to your audience, and instead of shaking your heads at millennials for being too sensitive and convincing yourselves of your own rightness, you should be taking a moment to reflect on what messages your votes are sending. “Almost” isn’t good enough anymore, and “close enough” doesn’t count. It’s time for the Grammys to start acknowledging just why the awards matter, before the increasingly diverse audience decides they don’t matter anymore.