Growing up is tough. It’s also hilarious, embarrassing, overwhelmingly dramatic, traumatizing, and heartbreaking, which is why so many different genres of film have tackled the coming-of-age narrative. These stories are universal in nature, they bind us together, forging bonds through awkward “firsts,” frustrated rebellions, anxiety-inducing dilemmas. They’re tales of longing and loneliness, confusion, desire, dread, and a singular uncertainty that comes with innocence lost. They’ve been mined for humor in raunchy comedies, weaponized for grief and misery in romance dramas, idealized in teen rom-coms but, oddly enough, some of the best versions of these journeys to adulthood come from fairy tales – with a twist.

Dark fantasy is a vehicle that plenty of filmmakers have utilized to map out the treacherous road to adolescence. Movies about young witches and wizards maturing through an apocalyptic battle of good vs. evil, stories of little girls exploring womanhood through labyrinths, tales of monstrous creatures stealing innocence while very real war wages in the background, all of these have been used as plots to further the examination of this most mysterious transition. And unlike films that poke fun at the more cringe-worthy aspects of teenagedom or movies that focus on the heightened emotions stirred by budding hormones and ever-present angst, works of dark fantasy are able to offer a kind of insight, an understanding and explanation of these frustrating experiences that other films often can’t.

They do this, as we see most clearly in Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, by getting inside the mind of a child, instead of viewing their story from afar. Ofelia, the film’s main character, is a young woman forced to mature during a time of upheaval and oppression. Civil war ravages her home life, so she escapes via a stone labyrinth and a belief that she is the reincarnation of a princess, meant to return home and live forever. Through trials that grow increasingly darker in nature, we see Ofelia reckon with the terrifying realities of growing up. She encounters nightmarish creatures like the Pale Man, who seek to steal her innocence. She ventures into mystical, foreboding forests which serve as metaphors for the equally confounding voyage through puberty. She confronts monsters, both real and imagined, in a bid of self-discovery where completing each task takes her one step closer to realizing the power that she holds over herself.

Del Toro uses Ofelia’s childish dreams and active imagination, not as a cautionary tale or a joke, but as a means to understanding the momentous challenges children face when they grow up surrounded by chaos, living in broken homes, orphaned by war and disease. Ofelia is very much on her own, a scary notion for anyone let alone a young girl, and del Toro respects the gravity of her experience, even if it is filled with fairies and magical labyrinths. He’s able to ground the tangible fears of adulthood in a larger tale that induces horror and wonder.

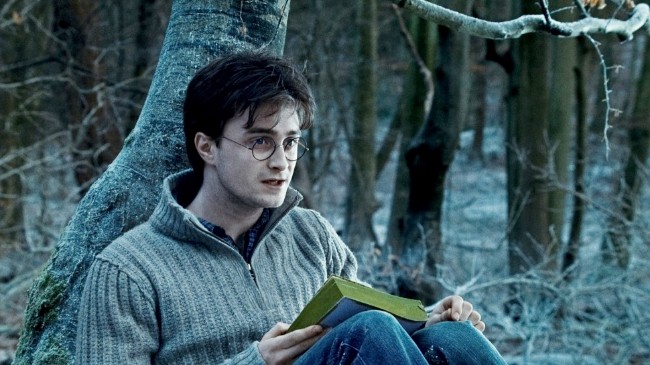

It’s something that J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, adapted to screen by directors who increasingly tapped into the story’s more macabre roots, does exceedingly well, too. Though the story of the boy who lived begins light-heartedly, with the discovery of a magical world kept secret from our own where children go to school to learn the art of witchcraft and wizardry, very quickly we’re thrust into the darker nature of this childhood fantasy. Over the course of eight films, we see Harry and his friends grow from bright-eyed youngsters learning to fly on broomsticks to hardened adults tasked with defeating a great evil. The films use tropes from the fantasy genre to empower their hero — Harry is special, he has abilities and a destiny that fuels his quest — but the darkness sets in when Harry begins to question his own nature, how closely he’s connected to the evil he desperately fights against, how much he can trust the adults offering him their help.

Through Harry’s miscellaneous adventures, we’re introduced to aspects of a fantastical world — dementors, hippogriffs, time-turners, and Quidditch — but with every wishful fulfillment of common childhood fantasies, we’re confronted with their consequences. We see the soul-draining toll of dark magic, the chaos that reigns when trying to alter history, the bloody aftermath of a Quidditch match. Worse, we see examples of loss, grief, sacrifice, and a questioning of self that feels especially poignant to the time in life that these characters are going through. They’re isolated, alone, and suddenly realizing that saving the world, and themselves, is not something they can count on older, more experienced adults to handle. How many of us have come to the same realization, that we’ve reached an age where we must do our own rescuing?

That’s what dark fantasy gets right about aging better than any other genre: the idea that ultimately, maturity means we’re in charge of our own destinies. Through otherworldly settings, unnatural creatures, mythological beings, and more mystical elements of magic, characters are granted the freedom to ask questions every child entering adulthood struggles with (where do we come from? why are we here?) while taking them on thrilling adventures that help fans discover the answers for themselves.

If anything, dark fantasy gives us permission to exercise our imaginations when it comes to these heavier realities of growing up and losing that sense of childhood wonder, and when it’s done well, it can even give us a bit of that wonder back.