It’s been said that if you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere. But I don’t think that’s true, at least when it comes to indie rock. In fact, I would argue the opposite. A paltry percentage of Americans actually care about or even know what indie rock is. But there are a lot of people in New York, so that paltry percentage nets a relatively large number of listeners. Therefore, lots of bands that can’t draw a crowd anywhere else can do still do relatively well in New York. It’s more like, “If you can’t make it there, you can’t make it anywhere.”

This is why I decided earlier this month to head to Utah, possibly the least NYC-like state in the union, to catch up with one of 2022’s most hyped indie artists, Bartees Strange, while he was on tour there.

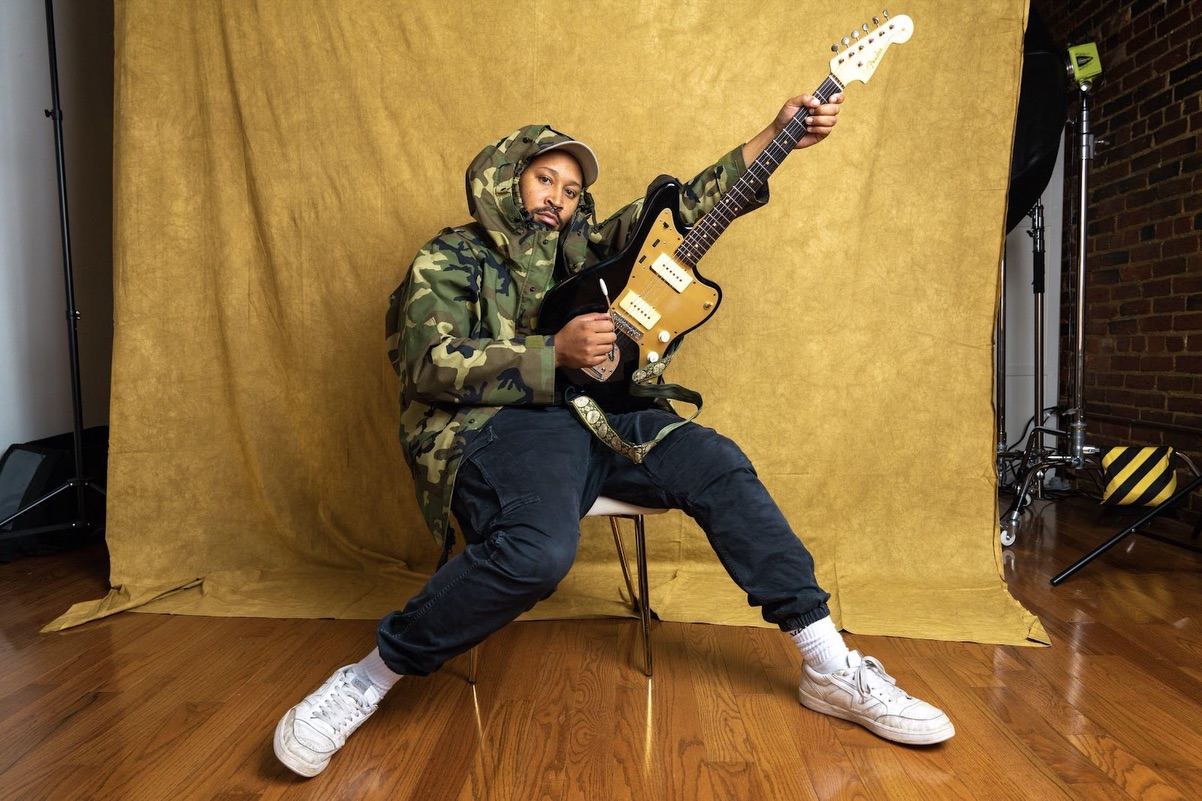

If you read music publications, you are likely already familiar with this 33-year-old singer-songwriter. For the past few years, he has been hailed by everyone from the New York Times to Pitchfork to NPR as a breakout star. (For the record, I also literally called him a “breakout star” in a column back in 2020.) Upon the release of his excellent second full-length album Farm To Table in June, Strange was praised for his musical range — he melds rock with hip-hop and funk and country and subtle jazzy grace notes, and makes it sound coherent and fresh and alive — as well as the political consciousness of songs like the psych-blues ballad “Hold The Line,” which addresses the murder of George Floyd.

Beyond his music, Strange is just an easy guy to root for. His background slots him as an underdog — he’s a Black man in a predominantly white music scene; he got indie-famous in his 30s in spite of the youth-obsessed, TikTok-ification of indie culture; he’s a country kid from flyover country flourishing among the coastal elites; he sees himself as fundamentally uncool and yet (as he sings in “Cosigns,” Table‘s first single) he’s now pals with some of the trendiest indie stars on the planet: Phoebe Bridgers, Justin Vernon, Lucy Dacus, and way too many others to name.

“It seems like the sky’s the limit with him,” says Bryce Dessner of The National, Strange’s favorite band, who invited him to open five dates in the western United States and Canada this summer, including the one I traveled to see. “I could see him having a really vast career based on what I’ve heard and just seeing him on stage. He’s got big things ahead of him.”

But all of this is just conversation. What matters — what actually moves the needle – is whether you can get in a van, drive several hours per day through the heart of America’s sprawling and scenic emptiness, set up for a gig, and get people to turn out and embrace your music. If you can’t do that, then all of the glowing reviews and flattering profiles and hyperbolic tweets amount to empty chatter.

Can Bartees Strange make it in the weird, wild West? I wanted to find out.

✌🏾Last night in Missoula, So beautiful. So gorgeous to play on a mountain and to meet so many kindpeople. Will not forget! We hit again with @TheNational in Ogden Utah. My third time in Utah in the last year 😵💫Here’s Us singing mistaken for strangers again! 🤘🏾♥️ pic.twitter.com/U859h7Qryy

— STRANGE (@Bartees_Strange) August 9, 2022

***

Three days before my flight to Salt Lake City, I get Bartees on the phone. I had last talked to him two years prior, upon the release of his debut full-length, Live Forever. At the time, he was trying to launch a music career at possibly the worst time in modern history to launch a music career. It was September 2020, and we were six months into Covid lockdown. Hope for a vaccine was on the horizon, but almost half of Americans were already expressing skepticism about taking it. The irony of releasing an album called Live Forever in this context seemed more cruel than funny.

Nevertheless, he pretty much … pulled it off? A former Division II college football player, Strange is more outwardly confident, competitive, and tenacious than most indie musicians I’ve encountered. This is, after all, a scene that still puts a premium on feigned apathy, even when it’s a barely adequate disguise for unbridled careerism. But Strange doesn’t even attempt to put on that kind of sham performance. He wanted to make it, and he worked hard to make sure he would, even in the midst of a pandemic. In the spring of 2022, he signed with the prestigious indie label 4AD, home to The National and countless other indie A-listers. It signaled his arrival as a major player in that world.

The day Live Forever was released, he started making Farm To Table. Unlike his debut album — which was preceded by an EP, Say Goodbye To Pretty Boy, which is made up mostly of radically reimagined covers of National songs — he had a bit of a budget this time around. He could afford to hire players for a backing band, which were culled from the Brooklyn art-pop scene he discovered in the 2010s that also includes fellow rising indie musicians L’Rain and Keiyaa.

The extra time and money is apparent in Table‘s silky sonic tableau; it is simply one of the best-sounding indie releases of the year. “I didn’t have to get on YouTube and learn how to compress drums,” he says with a laugh. (Strange has kept up his prolific pace and says he’s already close to finished with his next record. “It could be finished, if I wanted it to be,” he says. “I’m going to sit for a minute and I’ll come back to it in a little while.”)

The early jump on Farm To Table paid off by the summer of 2021, when tours started to slowly resume and Strange found himself as the most in-demand opening act on the indie circuit. Tours with Bridgers, Dacus, Courtney Barnett and Car Seat Headrest followed in quick succession as the calendar flipped to 2022. The busy road schedule immediately put Strange on a steep learning curve. “Before 2021, I’d never really toured like this,” he says. “My longest tour, I think, was a week with a friend, playing bass in their band. So I went from that to doing full national tours.”

After the relative idle of the shutdown, Strange now had to rapidly build his own touring infrastructure. “It’s just buying a lot of shit,” he explains. “It’s buying a van, buying a trailer, hiring a band, making sure everyone’s paid on time, getting a business manager, having a booking agent. And then you just hope it’s solid so you can play shows without stressing out.”

Inevitably, things happen that you can’t plan for. For instance, in July he waged his first European tour as a headliner. The first date was at Rock Werchter, a huge festival in Belgium featuring many of the very biggest bands in the world: Metallica, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Pearl Jam, Imagine Dragons. Unlike the guys in those groups, Strange still sets up his own gear. A few minutes after plugging in before showtime, he noticed something troubling: His pedal board was smoking. “I’m watching my pedals catch on fire from backstage,” he says, “and we go on in five minutes.”

Here’s a lesson for other musical rookies about to tour in Europe that Bartees Strange learned the hard way: The power sources over there shoot out about twice as much electricity as the ones here in America. The surge wrecked his pedals. “I had to change the whole setlist in two minutes and just play it for more than 2,000 people,” he says. “And that was show number one of the tour.”

Having survived this literal trial by fire, Bartees quickly learned to navigate the psychological highs and lows of touring life. There was the amazing two-show run in Toronto with Car Seat Headrest, when everything clicked and they had a great monitor engineer for once. And then there was the disaster in Tacoma with Dacus, where the audience looked like it wanted to kill him. “The thing that I’ve learned about touring,” he says, “is every show is not going to be a winner. A lot of shows, in fact, might hurt spiritually and make you question your entire life.

“But then you have moments where you just feel so present, and you begin to realize that it’s 50 percent about the music and the other half is about being present in the moment, and just taking whatever comes and just channeling it into a performance. Every performance is going to be different no matter what.”

My plan is to fly out to Salt Lake City the day before the show, spend that night doing whatever it is people do in Salt Lake City, and then drive 40 minutes north the following afternoon to the show in Ogden so I can spend time with Bartees before soundcheck.

When I pitched this story to my editor three months earlier, I had zero expectation that he would say yes. My motivation was mostly self-interest and entirely perverse: I like Bartees Strange and The National, but I also felt that this was my one and only chance to spend time in Salt Lake City, a place I had up until that moment never even considered visiting. This is not an insult to the Beehive State’s largest city — there are hundreds of mid-sized towns in our country that many of us will never think about and might even secretly suspect don’t actually exist unless we happen, by chance or company expense account, to have reason to travel there. Anyway, here was an opportunity for some Wild West adventure.

My first thought upon landing in Salt Lake City is, God, America is a big place. Honestly, it’s way huger than you probably appreciate. Though if you live in Utah, you likely have a better understanding of the vastness. Boundless expanse is a way of life out here. There are mountains and lakes and acres and acres of arid terrain. Nothing is nearby. The temperature always looms around 100 degrees. This part of the West is not crowded, but it is lonesome.

As I sit here, Bartees and The National are in Bonner, Montana, more than 500 miles to the north and a seven-hour drive. When they leave here, they will travel to Dillion, Colorado, which is just under 500 miles to the east and another seven-hour drive. Getting into my rental car, I ponder what it must be like to have to stack 500-mile drives over several consecutive days. Even with the eye-popping beauty of the scenery, this does not sound fun. Luckily, my hotel is only 1.7 miles away.

The isolation of Salt Lake City naturally breeds a unique local culture. I’ve gotten this far into the story without typing “Mormon,” which I consider a personal achievement, but yes the innate Mormon-ness of the place is undeniable. When you’re downtown, you can’t take in the mountain vistas that ring the city without also seeing a monument to the Church Of Jesus Christ Of Latter Day Saints lurking in your peripheral vision. But I don’t want to reduce Salt Lake City to a series of Mormon cliches. There are other distinctive attributes. The High School Musical films were made here. There is a surprisingly vibrant Mexican restaurant scene. You can’t order a cheeseburger without someone putting some pastrami on it. Famously, if you get pizza delivered to your hotel room, you might get sick and subsequently be willed to iconic feats of sports excellence. There is no other city quite like it.

Of course, this is also a place in which The National and Bartees Strange can sell approximately 7,000 tickets, so it’s not that different from any other American city populated by at least 200,000 people. During my brief drive from the airport to the hotel, I tune into the local listener-supported radio station, which is advertising a concert taking place that night by The Head And The Heart during a progressive talk show that “plugs you into Utah’s grassroots activists, community builders, punk rock farmers and DIY creatives.” Unfortunately, during my stay in town, I do not personally encounter any punk rock farmers.

That night, after dining alone at a Mexican restaurant that several people insisted I visit— it was very good! — I ventured downtown. In the manner of the sleepy Midwestern cities with which I am intimately familiar, parking is abundant and free after 8 p.m. I end up at a hipster bar with rooftop seating and a vintage soul playlist that sounds like it was curated by the music blog Aquarium Drunkard.

After ordering a beer, I take a seat and start texting musicians and comedians I know who have toured here in the past. What they tell me is remarkably similar, and jibes with my own experience — very nice people, pretty weird vibe. One person likens Salt Lake City to Mars, which seems apt. Another person recalls playing an ultimate frisbee retreat in the mountains outside of town. (“I thought they were going to harvest my organs,” he deadpans.) Yet another musician friend chimes in, with debatable irony, “I do admire their commitment to the grid system.” (The downtown grid truly is easy to navigate.)

The next day, I ask Bartees if he’s ever played Utah before, and he replies that this is his third time here in the past year. The first time was with Dacus, and Brandon Flowers of The Killers showed up at the gig. This is such an on-the-nose Utah reference that I wonder for a moment if he’s joking, but he’s not.

“I was like, ‘Damn. Weird place,'” he says.

***

The afternoon before showtime, I pull up to the venue five hours in advance of Bartees’ set. Strange and his band arrive at around the same time, and after meeting his tour manager I’m brought over to the subject of my story and we meet in person for the first time.

We decide to head over to a coffee shop a few blocks from the venue for the interview, even though the temperature is already north of 90 and coffee sounds about as appealing as a parka and gloves. But the coffee shop is nice — the barista is playing ’70s soft rock hits and at one point Bartees and I stop talking to note how pleasant it is to hear “Summer Breeze” by Seals & Crofts on a hot August day.

“National fans are so … it’s like being a Deadhead,” he says as we take a seat outside. “It’s like a cult. So, when you’re just like, ‘I love them just as much as you,’ it becomes a very low pressure and fun show. It’s pretty sweet.”

The Ogden concert is smack dab in the middle of his five-show support tour. The first night was in Calgary, and the National guys reached out beforehand and asked if Bartees wanted to sing a song with them. Bartees threw out “Murder Me Rachael,” a deep cut from their second LP, Sad Songs For Dirty Lovers. (The lyric that Say Goodbye To Pretty Boy references comes from that song.) But a more conventional standard, “Mistaken For Strangers,” was settled on instead.

“I was so emotional that I blanked on the first verse,” he says of the Calgary performance, which luckily wasn’t the one that went viral a few days later. “Afterward Aaron [Dessner] said, ‘Don’t worry, Matt does that all the time.’”

Bartees had never met the members of The National in person before this tour, though they apparently became fast friends. “Aaron was like, ‘You should come up to Long Pond whenever you want.’ And I was like, ‘I will pull up.’ I wanted to hear that forever. He’s kind of, in a way, a role model, in terms of his career and what he’s doing and how hard he works.”

Bartees pulls out his phone to show me a video from the tour’s second show in Montana. He’s on stage playing “Hold The Line,” and it’s the part during the guitar solo, which sounds like a cross between Eddie Hazel funk and David Gilmour spaciness. “This song is about George Floyd being killed. And there’s all these big beer-drinking white guys in the front row, and they’re just like, ‘The solo kills,'” he says. I watch the video and the big beer-drinking white guys are indeed swaying back and forth with their arms extended to the sky like they’re witnessing Jerry Garcia play “Morning Dew” one last time.

“It’s like, ‘Yeah dude, that’s great. Connect to that.’ There’s going to be someone else in here that connects to the words. There’s going to be someone else that connects to the vibe. Not every song is for everybody, but I’m not for everybody.

“But I think I can open people’s eyes a little bit,” he continues, “because I’m a person, and I don’t think everybody in Montana gets to meet a person like me, which definitely changes how they see the world. So I feel almost even more emboldened to just be myself, and just play my set, and just be like, ‘This is who I am. This is how I see the world.’ And be like, ‘You’re okay. too.'”

When Strange has played “Hold The Line” at other tour stops, he’s led the audience in a “Fuck The Cops!” chant. But now that you’re in a more conservative part of the country, I ask, I’m guessing you won’t be doing that here?

“No. But that’s more out of respect for The National,” he says. “I’m not trying to make it hot for them. I want to be the easiest, most cool, chill person to work with ever, so I’m asked to work with them again. You know what I mean? It’s about just getting the gig at this point. And then maybe if we know each other for long enough, I’ll be like, ‘By the way, fuck the police.’ But no, that’s not it right now.”

I ask if he has any thoughts on why he’s been such a popular opening act lately for white indie acts. He pauses for a couple beats with a knowing smile on his face.

“I have some thoughts. I don’t know if I would share all of them. But I think — I hope — it’s because my music is good. I hope it’s because I’m doing something different with my music, and I sound a little different. That’s what I hope. I hope the people that are bringing me on just genuinely like me. And when I meet them, that’s how it feels.”

Do you ever doubt that?

“Of course. Sometimes I’m like, ‘Am I just being tokenized?’ But then I’m like, that hasn’t stopped me from doing anything else I loved. I mean, I want to do these things. I’m not going to not do it. And if that’s the way I get in, that’s okay. As long as I’m in, I can do what I want to do. Because I am getting fans.”

In previous interviews, Strange has talked about opening up more space in the indie world for Black musicians. While he clearly takes this seriously, I wonder if he also resents it sometimes. Wouldn’t it be nice to just be another up-and-coming indie artist?

“No, I’m grateful that I can do it. When I watch a person in the NBA or the NFL talk about politics and they totally fuck it up, and I’m like, ‘Damn I wish that was me. I would’ve nailed it,'” he says. “I feel like in the indie rock space, I’m like, ‘Yo, I’ve got a lot of experience working in different movements, and I have an understanding of the world, and I have a perspective.’ I think it’s good that I can be someone that can open the door in a thoughtful way that are bringing people in and putting people in positions where they can do their thing, and I’m aware of it. It’s not an afterthought. It’s a part of my mission.”

The next stage of that mission will be leaving his “opening act” status behind, perhaps permanently. His first American headline tour commences in November, and he’s already dreaming big.

“When it’s my show, I’m definitely trying to cultivate a vibe in the room,” he says. “My shows aren’t like everyone else’s shows. It’s heavy. I want the room to feel thick. Like church.”

He tells me about his background playing religious music, and how before church all the singers and musicians would pray about being a vessel for a higher power. “If you get enough people that really believe that, that’s why the choir sounds so good. It’s just not about you at all,” he says. “And I feel like with my shows, everyone may be coming to see me, but I don’t see it that way. I see it as they’re all coming to feel what I feel, to experience something together. And so I want to feel what they feel, too. I try to just get out of my head and be like, ‘Fuck it. Who cares?’ Just let it run through you. It’s a gift to share.”

Weirdly — I swear I’m not making this up — a guy rolls up behind us on a skateboard as Bartees is talking about being a vessel. And then he pops up off the board and starts to play piano, because there’s a piano sitting on the sidewalk for some reason.

Bartees and I exchange “is this really happening?” glances. It’s a moment of incredible serendipity. But it’s also pretty loud, and I worry about picking up Bartees’ words on my digital recorder, so I ask him to stop. The guy shrugs, hops back on his skateboard, and floats away, returning to the place from which he was conjured.

***

After Bartees departs for soundcheck, I settle in for my scheduled interview with Bryce Dessner. Only Bryce isn’t at the venue. Nobody from The National is at the venue. They are all at an undisclosed location — an AirBnB, I’m told — working on the ninth National album. Instead of a backstage interview, I am talking to Bryce on my phone inside of my stupidly hot car out in the parking lot.

“It always feels like we cook up these albums, they come out, and then we reinvent things live,” Bryce says. “I think that this record — partly because of COVID and partly because of vinyl delays, and then coming back on tour — we’re not rushing it.”

I know from listening to recent fan-recorded bootlegs posted online that the band is playing several new songs on the current tour: “Tropic Morning News,” “Grease In Your Hair,” “Ice Machines,” “This Isn’t Helping,” “Weird Goodbyes.” That last song was just released as a single this week as a collaboration with Justin Vernon of Bon Iver.

On stage, these songs have been more guitar-heavy — with Aaron and Bryce trading solos — than anything The National have put out in at least a decade. But as of earlier this month the album was still evolving.

“Things we’re doing on stage have made their way back on the record, and then been developed on the record and then that’s affected the live show,” Bryce says. “We’re sitting in a space right now, recording a bit. And we actually have also recorded onstage. The whole record’s not that, but there’s elements of that.”

Before we pivoted to his own band, Bryce confirmed a story Bartees told me about Bryce advising him on which European cities to focus on at this point in his career. Paris and Brussels, in particular, are great markets with loyal fans who will always love you, especially if they feel like they’re getting in with you on the ground floor, he suggested.

“We were lucky to meet Michael Stipe and R.E.M. around Boxer,” Bryce recalls, “and it was a moment where they encouraged us with what we were doing. In a way, they saw us as heirs to the world that they had created. Obviously they’d had much, much bigger hits than we’ve ever had, but he was really pushing us to dream bigger.

“Someone like Bartees, he seems ambitious in a good way. He makes me think of musicians who are timeless in a way. So yeah, we’re around. If he ever needs help, he can call.”

By now, it’s time for Bartees and his band to hit the stage. It’s 95 degrees at showtime, but it’s that “dry” heat people out west talk about when trying to convince themselves that it doesn’t feel like you’re walking with a sweat sock over your face. When the musicians stride out, it’s almost dusk and the audience is indifferent. The opening song is “Black Gold,” the penultimate track from Farm To Table, and the sound is glitchy. Bartees’ microphone doesn’t appear to be working. Momentum is sputtering.

But the technical issues are short-lived. It is now quickly apparent that the band is fantastic — I don’t remember the last time I saw a group of players in an indie-rock context play with such commanding force and finesse. They seem capable of playing anything as they extrapolate Strange’s songs, turning them into lysergic EDM funk fever dreams. The star for me is drummer T.K. Johnson, a powerhouse who locks into deep grooves with bassist John Daise and multi-instrumentalist Graham Richman. But the spotlight also shines brightly on lead guitarist Daniel Kleederman, particularly on “Hold The Line,” which is prefaced by a speech Bartees gives about seeing George Floyd’s young daughter, Gianna, on the TV news.

“I thought, ‘This is horrible,'” he says. “Another Black kid has to grow up so fast.”

As the show unfolds, you can feel the crowd being won over. By the time Strange gets to his cover of “Lemonworld” — which transforms The National’s low-key comedy of manners into a cathartic electro-punk anthem — that “thick air” feeling that Bartees spoke of earlier has been achieved. The audience is with him. They give him a hearty cheer as the band exits the stage. When he comes back to load up his gear, they cheer loudly again.

He’s made it here. He can make it anywhere.

One thing I’ve learned from this tour with @TheNational is that meeting your heroes can actually be a really wonderful and special experience. Extremely generous and thoughtful gifted people. Ogden was a beautiful show. Last one is tomorrow ♥️ pic.twitter.com/ykXebFxJ8j

— STRANGE (@Bartees_Strange) August 10, 2022