Walton Goggins made a solid living playing weaselly live wires long before we cared much about who he was. But the Georgia-bred actor was such an enjoyable weaselly live wire that people in the know kept asking him back. Tarantino notably cast him in both Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight — after memorable turns in The Shield, Justified, and Sons of Anarchy — until Goggins inevitably became the kind of character actor whose presence promises a little jolt of excitement every time he shows up.

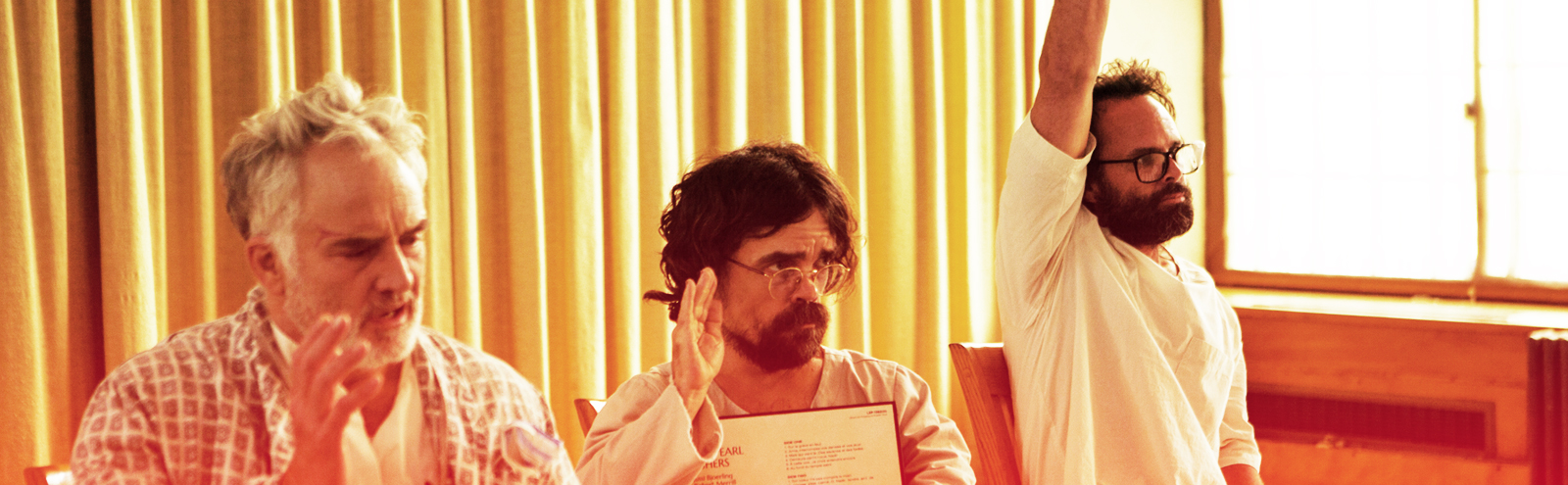

From there it was only a short jump to bigger and more varied roles. While he’s still as enjoyable as ever playing any wiry con man, as seen in Vice Principals and The Righteous Gemstones, these days Goggins also gets to play everything from sympathetic network leading man (The Unicorn, on CBS) to a schizophrenic who thinks he’s Jesus, in Three Christs, an arthouse drama starring Richard Gere as a groundbreaking psychiatrist, which played festivals in 2017 and is getting a limited theatrical run courtesy of IFC this Friday.

I’ve always found journeyman character actors more interesting than leading men, but Goggins has a rare and singular ability to evoke both memorable weirdo and acquaintance you’ve known for years, both exotic and familiar. “Con man with a heart of gold” would be an oxymoron if not for Goggins. There’s an ineffable authenticity to him, the sense that he was a character before he was a character actor. It’s this quality more than anything else, I think, that allows him to be convincing as so many different types. He’s redolent of unsoftened oddness, such that he can play any flavor of odd. In one of his first roles, he played a frat boy who barked like a seal on Beverly Hills 90210.

And of course, there aren’t many things more enjoyable than seeing brilliant craftsmen who’ve toiled in relative obscurity for years (inasmuch as acting can be considered “toil”) finally become household names. If Goggins isn’t there yet (he’s certainly a name in my household) he must be on the verge. The Gogginsonnaissance, people. It’s time.

I have to say my fianceé doesn’t care about 95% of the people I talk to, but when I told her I was talking to you, she actually squealed.

Hey, I’ll take it, man! That’s awesome. You just made my day.

Do you think that says anything about the arc of your career? Do you find different sorts of people recognizing you these days?

You know what? I do, man. I got to say, it’s an embarrassment of riches. I’ve been walking for a very long time and without any great plan, only looking at what was kind of before me — playing it as it lays, I suppose. To be able to walk down any given street in any city and to have lengthy conversations about a variety of different things I’ve been fortunate enough to be a part of is, I think, that’s what any person in my business would tell you that they ever wanted from this.

Tell me about the early days of your career. What were some of the first jobs that you booked?

Oh, God. The very first job that I did, because I’m from Georgia…most people that are from my part of America all came to Atlanta to work. There was a thriving film community there, but there was also a big television show that was filmed outside of Atlanta called In the Heat of the Night. That was the first job that I ever got and booked. It was with Leo Penn — Sean Penn’s father — who was directing it. It was a pretty big role, actually. I didn’t really study, I was just this kid who had a lot of feelings and a very strange kind of upbringing, and an aunt and an uncle who were both in the theater that I watched telling stories and I grew up with a group of women and people that were great storytellers. That’s what attracted me to this business in the first place.

Anyway, I found myself the very first day at work with Carroll O’Connor and Leo Penn. And Carroll O’Connor, to me, was the fucking man. I’m sitting there outside — and I remember this like it was yesterday — they blocked the scene. I didn’t know what “blocking a scene” even meant, and they came in and they said, “Well, this is your mark.” And I said, “OK, what’s my… Oh, you want me to stand here? Oh, okay. You want me to see to come in the room and you want me to stand here? Okay. All right, great. Then you want me to say these lines to… Oh, to you, Mr. O’Connor? Okay. Yes. Okay. I got it.”

And I walked outside, man, and I had a fucking panic attack because, Walton, what have you done? What have you talked to yourself into, man? You don’t know what the fuck you’re doing. What are you doing? You have no idea. You have no business being here. I was unraveling, kind of like sitting outside leaning against these lockers in this school and they were blue and orange actually, and I just remember in that moment saying, you know what? It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter that you don’t know what you’re doing. You’re here for a reason and just go be as honest as you can. If it’s horrible, it’s horrible. It’s okay. And they yelled action, and I exhaled. I walked in, overshot my mark by three feet, said my lines, and I turned around and I walked out the door. “Cut! Okay, Walton, we’re going to have to do that again. This time you got to step on that mark that’s right there.”

I said, “Okay, not a problem.” He called action again, I walked in, I looked at my mark the whole time I walked in, I stood right on it, I looked up, and I said it with conviction from my heart. I turned around and walked out. We did it one more time and that was it. Everybody has their first time — everyone. In everything in life, you have to begin somewhere, and that was the beginning for me.

I have a friend who is from Douglasville. He said you’re the most famous alumnus of his high school. Are you like a local hero now?

I mean, it’s like however you define that. I mean, we came from Douglasville, Georgia, right outside downtown Atlanta, but it was 18 miles away, and it may have well been a little small town in the middle of nowhere. That’s how we kind of looked at it. There were a couple of rival high schools, and it was a tight-knit community. There were funerals, sometimes four in a month, because it was somebody’s cousin or an aunt or a great aunt that would pass away. So I know a lot of people in my hometown, and everybody knows each other. I love where I come from and those are my people. I suppose if under the analogy that all boats rise, whatever it is that I’ve accomplished in my life, that if my community feels a part of that, I think that’s the truth because that’s a part of who I am.

This movie, Three Christs, is the first role that I’ve seen you in a while where you’re not using your Southern accent. Early in your career was your Southernness a selling point for you?

Absolutely. I think for every actor, I suppose if you’re Italian and you’re from New York, chances are you’re going to play somebody in the mafia, right? I mean, we’re all defined by where we come from and how we sound. That’s the part of the story. I think that is the paper bag that we’re all trying to punch our way out of in some form or fashion. For me, I sounded the way that I sounded, and I looked the way that I looked, and of course I was going to… Not of course, but the opportunities to be cast in those roles were really kind of the opportunities that came my way.

I’m very grateful for those opportunities. Certainly, early on I knew enough to keep my mouth shut and to listen and respect the fact that I was around people that knew more than I did. I learned a lot. I think that I’m one of those journeymen now, like so many of the people that I looked up to. And I’ve been around 30 years, man, and no one gave me anything. It was each step, I think the universe said, “Okay, you’re ready for this.” If I had gotten any measure of success beyond what I was capable of doing at any given point, I think that probably would have been it for me.

Coming up as a character actor, you must get a sense of the way other people, or casting directors, might see you. Do you ever find that that was different than the way you saw yourself?

Yeah. I think certainly early on, and the first 10 years of my life in Los Angeles. I absolutely understood how I was perceived and I knew that I had more to offer and that there were other things that I was capable of. But I wasn’t quite sure if I would be given that opportunity or how that would come about. As these things happen, sometimes the stars align and you get that opportunity to kind of redefine yourself for other people, but also for yourself. The Shield probably did that for me more than anything early on. At this point in my life I don’t, even for the last 18, 19 years, I don’t live my life or make my decisions as a reaction or needing to prove to other people that I can be more than what you think of me. I’ve said no to things that were extremely familiar for me, not for fear of being typecast, just because it’s something that I’d kind of done before or it didn’t speak to me. Something would inevitably come up that gave me an opportunity to participate, and it just so happened to change the way people saw me. I think that happens for everyone who sticks around long enough.

So are you a de facto member of the North Carolina Mafia (the group of North Carolina School of the Arts grads — Danny McBride, David Gordon Green, Jody Hill, et al — who frequently collaborate) at this point, after doing so many shows with Danny McBride and all those guys?

You know what? I think I can safely say without fear of being whacked that yes, I’m a part of that mafia. Maybe I’m just like a hitman for those guys. I don’t know, but it doesn’t really matter. I don’t care like how they use me, I’m just so fucking happy that they do use me. I’ve got a number of families now that I’m a part of, and circles that I’m a part of in this business, and I relish every single one of them. The North Carolina Mafia, if you will, the North Carolina School of the Arts alumni, graduates, I fucking love those people deeply. They’re family to me.

You guys make a good team.

Thank you very much for saying that. It’s a bigger compliment to me than it is to Danny, but I appreciate you saying it a lot.

So I’d just seen you in The Righteous Gemstones where you had the real smooth face and the big teeth and then in this one you have the big bushy beard. Is that all you? Is that enhanced at all?

That’s all me, buddy! Man, we went through so much telling the story, and knowing that maybe only three people would ever see it. I never anticipated anything beyond that because it was so difficult to find your way into it until I watched it with 1200 people at the Toronto Film Festival. It was a standing ovation. People got it. I think that’s all we ever wanted was for a minute, what does it feel like to live the reality of schizophrenia? What does that really look like up close and personal? I felt like we’ve done that and I’m really proud of it. I learned a lot about this disease along the way. I’m so proud to be a part of something that has such great empathy from the man who penned the book, and did the research, Milton Rokeach, and that he endeavored to just understand other people with kindness.

Thank you for talking with me. I really enjoyed it.

Right back at you, man. And tell your fianceé I said I appreciate it. Tell her Baby Billy says hello. All right, man.

‘Three Christs’ hits select theaters and on-demand January 10th. Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.