With Creative Minds, Uproxx shines a periodic spotlight on some of the most exciting minds in their fields.

With Creative Minds, Uproxx shines a periodic spotlight on some of the most exciting minds in their fields.

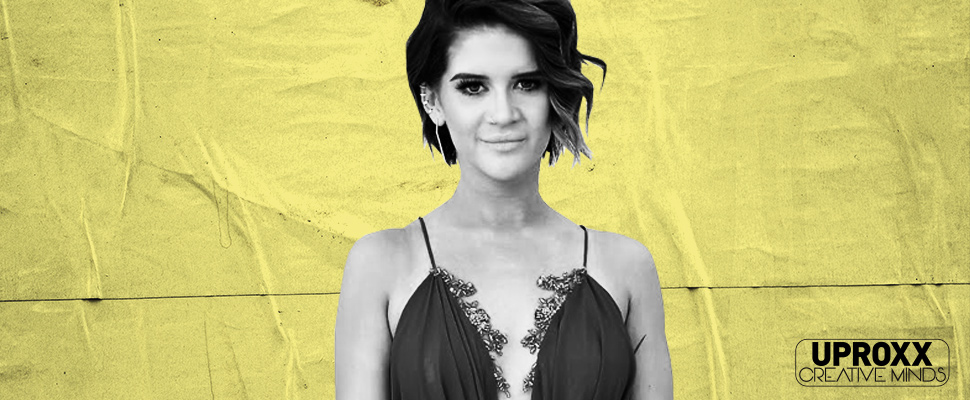

Maren Morris

A couple hits of Maren Morris’ burnished alto and feisty lyrics is all it’ll take to bring the uninitiated into her ever-growing “I don’t like country music but…” fold. It’s not that every country star needs to turn genre outsiders into fans in order to be successful, it’s just that with her impeccable style, larger pop culture references, and easy humility, Morris is one of those voices that easily supersedes what can be a niche or unnoticed part of the music industry.

Morris has been a Nashville fixture for several years, but like her friend Kacey Musgraves before her, it took that long for the powers that be in the country music capitol to sit up and take notice. When a sweetly sharp song called “My Church” started bubbling up on country radio back in January 2016, it felt like a defiant little miracle. Country radio has been notoriously unwelcoming to women since the tide turned toward rollicking bro-country crossover joints in the mid to early 2000s, and it’s been an uphill battle for even legacy female artists to crack the airwaves.

But Morris took all that stride, busting in with a crackling, warm sound all her own, one part pop hook and one part down-home-melody. She cites Sheryl Crow as one of her foremost influences and heroes, and like Crow before her, the 27-year-old Morris defies easy categorization. Her songs turn tricky corners with honeyed, sly sincerity and tie together disparate elements like the line “that’s like saying drunk girls don’t cry” as an ether for a friend’s shaky defense of a terrible boyfriend. She co-writes on every single track, and never sputters, only purrs; there’s not a song on her major label debut Hero that doesn’t hold its own next to the single the fueled it all, “My Church.”

But Maren’s 2016 breakout record, Hero, wasn’t her debut — it was her fourth full-length album. Perhaps that will give you a better sense of just how tough it is for women to become full-fledged mainstream stars in Nashville right now. Still, Morris made it look easy, building off the release of her self-titled 2015 EP as “My Church” skyrocketed straight to No. 5 on the Hot Country Songs chart, and eventually went platinum. Hero itself entered the Billboard 200 at No. 5 and topped the Top Country Albums chart. Numbers themselves aren’t proof of creativity, but in a genre that routinely shuns female talent, they illustrate a certain kind of determination and success that is extremely rare in the country at the moment.

The co-signs continued to pour in when Keith Urban enlisted Morris to open for him on a massive tour last summer, and the Texan native continued her hot streak this year when Hero earned her four CMA nominations, including New Female Vocalist Of The Year — which she won — and a whopping four Grammy nominations: Best New Artist, Best Country Album, Best Country Song and Best Country Solo Performance, which “My Church” went on to win. On that song, when comparing listening to the radio while driving to a religious experience, Morris joyfully asks “Can I get a hallelujah? Can I get an amen?” At this point, for her, there’s few other sentiments that fit. — Caitlin White

Hurray For The Riff Raff

Alynda Segarra was born in the Bronx and grew up listening to Motown and hardcore punk. Eventually Segarra found her way to down New Orleans — she used to hop freight trains, a nod to her hero, Woody Guthrie — where she learned the banjo and started exploring roots music. In 2007, she formed Hurray For The Riff Raff, and proceeded to build a reputation as one of the most forward-thinking and politically minded artists in the amorphous genre known as Americana. Each new album pushed Segarra a little closer to mainstream attention, most notably 2014’s Small Town Heroes, her debut on ATO Records.

For the latest Hurray For The Riff Raff record, The Navigator, the 30-year-old Segarra looked back on her life and contemplated her roots as a Puerto Rican woman growing up in the big city. Segarra’s childhood memories and contemporary observations about the experience of immigrants suffering in a modern-day America increasingly hostile toward outsiders informed a narrative that ran through her latest songs. For The Navigator, Segarra crafted a cinematic song cycle that followed the arc of her life, drawing on a variety of musical styles in her vivid story songs, including rock, folk, blues, and salsa music. The result is one of the year’s best and most fascinating albums, a record infused with a rich tapestry of personal memoir and political commentary. With a sizable body of work already in her rearview, Segarra is poised to further evolve into one of the more insightful singer-songwriters of her generation. — Steven Hyden

Solange

Anger is traditionally characterized as a negative emotion, particularly when it erupts in women, and even more specifically when it erupts in women of color. The trope of the “Angry Black Woman” has been so viciously mythologized in our culture, due to America’s racist foundations, that it’s still difficult to find representations in pop culture that allow a full spectrum of emotion to black women. All of this historical injustice was bubbling on the back burner, when a comment from a New York Times writer evoked a rage within Solange Knowles that led to 2016’s magnificent, simmering album A Seat At The Table.

This is an album powered by a quiet, necessary anger, yes, but it is also a record that allows her to express herself as so much more than just mad, even though understanding and listening to her anger is part of honoring the emotional labor that went into creating this. After the long tradition of silencing and stealing from women of color in America, it is a revolutionary act to praise this record for what it is — all history aside — one of the best albums to come out in 2016, period.

Solange skillfully weaves firsthand accounts from Master P about his childhood experience growing up in the segregated south, and building his No Limit empire, into her own stories about isolation, grief, motherhood, love, and yes, racism. “Cranes In The Sky,” a silvery distillation of the impact of systematic oppression rightly picked up a Grammy earlier this year for Best R&B Performance. Songs like “Don’t Touch My Hair,” and interludes from her mother, Tina Knowles, along with contributions from Q-Tip, Kelly Rowland, BJ The Chicago Kid, Kelela, Lil Wayne, and The-Dream make this album feel like a communal expression of the Black experience in America in 2017.

But despite all the other voices, Solange’s rises, weary, above the rest, demanding to be heard, and providing respite for all the others who have been listening, waiting for someone to speak for them. Across twenty-one tracks, Solo eclipses her first two albums and reveals what a record that is an accurate portrayal of her vision as an artist, unhindered by meddling from labels and other parties, sounds like.

As if the music itself wasn’t powerful enough, Solange surprise-released the album along with a full-color, glossy companion book full of gorgeous photographs, and appeared on SNL with the kind of costumes and choreography that made Björk herself look like an amateur. On A Seat At The Table, Solange pulled out a chair, put it up on the table, stood on top of it and declared: This sh*t is for us. The rest of us can watch quietly from the wings, appreciating a bona fide genius finally coming into her own. Rage can be a powerful weapon, but here’s to a world when that’s not what it takes to give a creator of this magnitude her due. — Caitlin White

Father John Misty

Starting in the early ’00s, Josh Tillman started putting out little-heard albums composed of threadbare (but often beautiful) folk-rock songs. When Tillman played these songs live, he would assume the typical folk-singer pose: Head down, hair in his face, and perched on a stool in a strictly downtrodden posture. Not surprisingly, this approach did not yield Tillman a big audience. So, when Fleet Foxes needed a drummer in 2008 and asked Tillman to join, it must’ve felt like a lifeline.

The rest, for indie-rock fans anyway, is history. In 2012, after completing a long tour with Fleet Foxes in support of Helplessness Blues, Tillman put a great new record, Fear Fun, under an incredible new moniker, Father John Misty. Like that, Tillman escaped his past as a sad-bastard folk singer and rebooted himself as one of the most colorful and provocative indie-rock stars of the ’10s.

The press cycle for Pure Comedy was Tillman’s highest profile showcase yet. With Kanye West keeping a low profile at the moment, there’s simply nobody who gives a better soundbite than Tillman. With a unique combination of humor, philosophy, and, yes, trolling, Tillman is as entertaining off stage as he is on. However, Tillman’s antics in the press shouldn’t overshadow his art — Pure Comedy is a beautiful, infuriating, humanistic, and deeply troubling masterwork that attempts to make sense of nothing less than the self-destructive nature of mankind. It’s a big record made up grand musical flourishes and intimate lyrical gems, the sort of gesture that justifies Tillman’s bombastic persona. Long may he run. — Steven Hyden

Pinegrove

Evan Stephens Hall works within a collective, as the frontman of the band Pinegrove, but his voice is reedy, singular, and mesmerizing; it’s the kind of voice that carries a band out of the obscurity of Montclair, New Jersey and into the national spotlight. As the primary songwriter for what is best described as one the best and most inventive rock bands of the last several years, Hall pinpoints the balladry of country music, the joyous anguish of emo, and the compelling brevity of short story vignettes, and rolled them all into one rousing and tender record called Cardinal. The album came out very early in 2016, and still managed to top our best rock albums list last year, building a momentum throughout the year that was undeniable.

After putting out a couple EPs and one self-released record, Meridian back in 2012, Cardinal was picked up by the Boston indie punk label Run For Cover records, a co-sign that helped catapult Pinegrove into the cult fame they’ve established. 2017 promises that cult following is about to erupt into full-fledged popularity, as the band kicked off the year with the release of a bunch of recordings from their 2016 tour for the live album, Elsewhere.

Hall and Pinegrove’s drummer, Zack Levine, make up the core of the band, which expands ever outward into a series of additional collaborators and members whenever necessary. The two inherited a friendship from their fathers, who were both jingle writers early on in their careers, and still play together in their own band, Julie’s Party. So Pinegrove’s sophomore album is something of a family affair for the guys, both Hall and Levine’s dads show up for guest spots, as does Hall’s brother, on guitar.

Cardinal clocks in right around 30 minutes, but even at just under half hour, it managed to become the kind of fiercely beloved album that kindles a cult following, sparks discussion about genre invocation, and has fans poring over lyrics for clues about what’s fictional what is fictional and what is autobiographical. Hall’s writing is so intimate and evocative that he’s had to remind listeners again and again that songwriting can be a fictional process, and has similarly battled off the designation of Pinegrove as “emo,” arguing that, as a genre, emo looked inward and he strives to look outward.

“Everything I sing, I sing for me,” he fervently declares on the track “Cadmium,” which may seem to disprove the above thesis, that is, unless you’ve heard a crowd passionately chanting it back, turning his personal assertion into their own public incantation. Cardinal is that kind of album, a record loose enough to assume the shape of your own pain, and all that flexibility is due to Hall’s moving, sometimes strained delivery, and his wry, incisive songwriting.

Influences like My Morning Jacket, Bon Iver, and a background full of surreal literature afford the band a measure of both the psychedelic and the intellectual that lifts them far above the menial impulses that rock and country often bow under. Instead, Pinegrove perfectly meld the golden finger-picking of early cowboy songs, heart-on-your-sleeve lyrics, and the crash and boom of traditional rock, pointing toward a more perfect union of genres and styles in the post-internet world. — Caitlin White

Adrianne Lenker of Big Thief

Though she’s only 25, Adrianne Lenker has already survived a lifetime’s worth of drama. Born into a religious cult, Lenker was fortunately removed from that bizarre existence by the time she was 4, though not without some inevitable strife. (She lived in 14 different houses by age 8.) Around the same time, Lenker started writing songs, due in part to the encouragement of her father, a musician. By her tween years, Lenker was already being groomed for a career as a kiddie pop singer, though she eventually walked away from that, too.

Perhaps all of those experiences account for how deep and assured Lenker’s songs already are. Her band Big Thief — formed with guitarist Buck Meek, a key collaborator that Lenker met in New York after attending the Berklee School of Music in Boston — debuted in 2016 with Masterpiece, a beguiling indie-folk record highlighted by Lenker’s lilting vocals and wised-up lyrics. One of 2016’s best LPs, Masterpiece is a bit rough-and-tumble compared with the forthcoming Capacity, which elaborates on the organic rootsiness of the debut with elegant arrangements that touch on psychedelia, Krautrock, and ’70s singer-songwriter pop. While Lenker had already distinguished herself as a promising young songwriter, Capacity suggests that she’s already learned about how to make evocative records that can take her heartfelt writing in alluring and unpredictable directions. — Steven Hyden

Lorde

From the time she was thirteen, Ella Yelich-O’Connor knew she was going to be a musical force. Or, well, maybe she didn’t realize it then, maybe it was way before that, as a child, piecing together poetry and lyrics, echoing the songs she heard out in the world and filtering them through her own scratchy, velvety alto. By the time we heard “Royals,” her most popular single to date, it sounded like Ella had been blazing through the pop world for years. But when that song came out she was barely sixteen; she’d never even left New Zealand.

It was back at thirteen, when her dad sent home recordings of her talent show performance off to a big record label, and actually got a response, it was when Universal Music Group A&R scout Scott Maclachlan heard the demo and almost immediately signed her to a development deal, that Ella’s mile-wide stubborn streak first became apparent. Plenty of child stars get sucked into the record label system before they hit their teens, paired up with songwriters and stylists, and churned out into run-of-the-mill pop stars. Not Ella.

Her taste was so specific, her urge to write and create so strong, that eventually, Maclachlan and his cohort let her have almost free reign. It seems impossible that she didn’t realize what her insistence would lead to, that she didn’t already have a vision of what Lorde would become, and exactly how she would bring that persona into being. By the time she released any music, at sixteen, the years spent honing and sharpening her sound and ideas meant that the first Lorde EP felt fully-formed in a way that music from an artist this young rarely does. This was the sound of someone who already knew who she was.

Paired with producer Joel Little, Ella crafted her alter ego, Lorde, and self-released that debut EP, The Love Club, on Soundcloud in spring of 2013. This was before most of her US fans discovered Ella, so sometimes this EP gets lost in the glow of Pure Heroine, her wildly successful debut album which came out that fall and incorporated most of th0se songs. All the bones of who Ella was, and who she would become, were present there on that initial five-song release; a girl who chafed at the glowing facade of cliques on the EP’s title track, who skewered unrealistic portrayals of wealth on the year-defining “Royals,” and whose minimalistic, dreamy electropop would recalibrate the entire sound of indie and mainstream pop in the years to come.

Pure Heroine earned Lorde two Grammys, for Best Pop Solo Performance and Song Of The Year, and she went on to involve herself further in pop culture by curating the Hunger Games soundtrack, befriending fellow pop star Taylor Swift, and remaining eagerly supportive and excited as a fan of other musicians. But then it all stopped and she sort of disappeared for a few years; she didn’t release any one-off singles, she wasn’t a guest on any high-profile collaborations, and didn’t give any sign of when she would return.

Until this year, when she came blazing back in early 2017 with the reason behind her long absence — she’d had her heart broken. This was the piece of her we hadn’t heard on The Love Club or Pure Heroine, the kind of gut-wrenching, world-shattering experience that functions as a crucible for a songwriter of her caliber. Now, she’s branched off from her initial work with Little, writing most of her new album with pop music’s best sidekick, Jack Antonoff, and taking her sweet time to refine the new material as much as her grief, love and musical impulses demanded.

So, this summer’s Melodrama, preceded as it is by the thundering, slammed-door pop of “Green Light” and the devastating, broken tenderness of “Liability,” will give us the next phase of Ella’s creativity. It’s a record that a thirteen-year-old couldn’t have conceived of, a coming-of-age album that will certainly place her among pop music’s greats. Though she’s been blazing all along, this time, she’s a forest fire. She’s never burned brighter. — Caitlin White

PWR BTTM

To fully appreciate why the pop-punk duo PWR BTTM is one of rock’s most enjoyable young rock bands, you really need to see them live. Imagine if Kiss was made up not of macho heterosexuals but rather two hilarious and smart individuals who identify as queer, and you have a decent approximation of the giddy extravaganza of sound and visuals at a PWR BTTM gig. Members Liv Bruce and Ben Hopkins dispense a never-ending supply of glitter, jokes, and catchy riffs, acting as both entertainers and BFFs to throngs of insanely devoted fans. It’s an incredibly festive and warm environment that’s welcoming to anyone, though there’s no question that a PWR BTTM show will mean more to gay, lesbian, transgender, and gender-nonbinary fans that have waited a long time for a band to call their own.

But until PWR BTTM comes to your town, the band’s new sophomore release, Pageant, will more than suffice. While no album could match the sugar rush of PWR BTTM’s live show, Pageant showcases the songwriting chops behind the spectacle. The PWR BTTM formula — guitar shredding plus witty and observational lyrics — is a very good vehicle for the band’s funny/sad explorations of identity, relationships, and the struggle to assert yourself in a world that can be reluctant to honor your humanity.

Pageant feels like a path forward. A band like PWR BTTM is crucial for the future of rock, given the genre’s retrograde history when it comes to interacting with the LGBTQ community. PWR BTTM signifies a brighter future in which the traditional look and feel of a guitar-oriented band is less codified and can exist successfully in any guise for a wide range of audiences. — Steven Hyden

Weyes Blood

Folk music has always been about time, something that Natalie Mering knows better than most. On her astonishing third album as Weyes Blood, A Front Row Seat To Earth, Mering immediately establishes herself as one of the foremost voices currently working within the folk realm, and one who is intent on bringing the ancient principles of this music firmly into the twenty-first century. For that alone she should be lauded as one of the most inventive and important songwriters of our current era, and in addition, her 2016 release unflinching confronts the delightful, decaying world of technology and mass consumption that millennials have inherited.

Too bad it came out just weeks before Donald Trump was declared president in an unprecedented, unexpected twist. There was little time or attention for existential folk music of a forward-thinking mystic in the wake of this political upheaval. But perhaps now, a couple months removed, Mering will begin to get her due as a composer and philosopher using music as a medium to convey her truths about the universe. Raised by extremely Christian parents, Mering soon abandoned these principles to pursue her own beliefs about spirituality, but the sacred underpinnings remained, giving her music a sense of the holy that is rare in secular culture.

After one year of studying music, Mering dropped out of college to tour Europe and develop her sound as Weyes Blood, a band name drawn from Flannery O’Connor’s novel, Wise Blood, and the ideal title for a project that similarly seeks to uncover and describe the twinned good and evil hidden in every human heart. This is dream-folk for those who spend their time worrying about the end of the universe, a new metaphysical music for a generation obsessed with eternal youth and have just begun to notice themselves aging.

Through the veil of romantic dissolution, Mering confronts specters of time and existence, grief and loss, pouring all this into unspooling piano ballads that sometimes build into insurmountable heights, like on “Seven Words,” when she erupts into beautiful, wordless scatting, or within the vulnerable questions of “Do You Need My Love,” that stretch themselves out over an aching and ominous undercurrent of ‘70s pop-rock. On “Generation Why,” Mering invokes a host of close, blueish harmonies to spell out “YOLO,” the term Drake coined to capture the desperate angst of our voyeuristic, all-things-at-all-times generation.

Perhaps Mering’s greatest strength is her ability to convey the decidedly specific hopes and fears of this “Generation Why” — or what the world insists on calling us, millennials — providing a voice to the smallest, shallow moments and greatest, deepest secrets, often within the confines of the same song. That she has chosen the ancient tradition of folk music to speak such timely prophesies only further cements her respect and understanding of the power and importance of the current moment. After all, folk music has always been about time. — Caitlin White

Jason Isbell

While Jason Isbell is now three albums deep into a career renaissance, his comeback from the brink of addiction is still no less remarkable. Back in the ’00s, Isbell was one of the most promising young artists navigating the divide between rock and country. He distinguished himself as a top-flight singer and songwriter in Drive-By Truckers, a band that already had multiple songwriters but nonetheless made room for Isbell gems like “Decoration Day” and “Outfit.” Embarking on a solo career in 2007, Isbell continued writing great tunes: “Dress Blues,” “The Blue,” “Alabama Pines.” But by the early ’10s, Isbell was stuck in a personal rut due to his substance abuse problems.

After finally getting clean and sober, Isbell rebooted his career with 2013’s landmark album, Southeastern. Finally, the promise he had showed a decade earlier when he joined the Truckers started to pay off, as Isbell redoubled his efforts and remade himself into one of America’s most respected songwriters. Isbell also took control of the business side of his career, starting his own record label, Southeastern Records. In 2015, Isbell enjoyed the highest charting record of his career with the excellent Something More Than Free.

Isbell’s forthcoming record, The Nashville Sound, builds on the thoughtfulness of his post-treatment records, Southeastern and Something More Than Free, while returning to the hard-rocking of his earlier records. Not long ago, it appeared that Isbell was a dead end. Now, it seems like Isbell is built to go the distance. This summer, Isbell will perform concert dates with Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan, and it’s no stretch to suggest that Isbell is among the artists who will continue on the legacy of those American icons once they’re gone. — Steven Hyden