How do you cope when you love Radiohead and live hundreds of miles away from the nearest stop on the band’s current summer tour? If you’re like me, you have been scouring YouTube for the latest concert videos and downloading secretly recorded audience tapes, though this has only intensified my overwhelming FOMO. As the tour’s rapturous reviews keep reiterating, Radiohead is absolutely killing it right now, reclaiming the majestic guitar jams that for years the band set aside in pursuit of more experimental tangents. In the process, Radiohead has embraced its destiny as one of the great arena-rock bands of all time.

As a long-time Radiohead fan, this is both a cause for celebration and — if you’re missing out — the source of profound anxiety. Each high point feels like a taunting jab. Why didn’t I just suck it up and drive six hours to Chicago? Wait, they played “Blow Out”?? [Looks up flights to Detroit.]

It’s worth noting that Radiohead’s latest peak as a transcendent live act comes 25 years after the band’s first North American tour, when the success of “Creep” made them a surprisingly popular stateside band. A year before Oasis and Blur ushered in American interest in Britpop, Radiohead was the rare British rock group to infiltrate the U.S. pop market, all due to a song that they would eventually resent having to play live. (Though, even on that contentious count, Radiohead has mellowed over the years.)

While Radiohead evolved well beyond “Creep” on subsequent albums, the song did establish the band’s central dynamic. Thom Yorke is the protagonist of “Creep” — he relates the lyric about the inherent alienation felt by an outsider, and his operatic voice conveys the song’s surging, self-pitying melodrama.

When I first heard “Creep” as a 15-year-old — the perfect age for a band like Radiohead to enter your life — Yorke was who I connected with. When I bought Pablo Honey soon after, he was the “star” of Radiohead in my mind. He wasn’t necessarily my favorite member — back then, I was an Ed O’Brien guy. (Even now, Ed is the one I would most want to hang out with, especially since he would be down to get high and listen to jam bands.) But Thom clearly was the guy that Radiohead was “about,” in terms of the point of view that was implanted on the band’s songs.

Every great band — even bands in which each member is ostensibly on “equal” footing — ultimately settles on a single narrative with a lead character. Sometimes that character is obvious, whether it’s Pete Townshend, Billy Corgan, or Hayley Williams. Other times a dynamic between two central figures is paramount, like Lennon/McCartney, Jagger/Richards, or Morrissey/Marr. In Radiohead, the public’s focus has always been on Yorke, and it probably always will be. He’s the singer, the frontman, and he originates the songs. If you love Radiohead, Yorke demands your attention.

But in the past decade or so, I’ve heard Radiohead differently than I once did. When I listen to “Creep” now, the focal point in my mind has shifted from the guy singing, “I wish I was special,” to the guy playing the blood-splatter riff in the pre-chorus, a violent eruption supposedly spurred by the guitarist’s desire in the studio to derail a song he despised. While Yorke’s voice and songs remain central to the band’s music, I’ve come to believe that he’s not the one who ultimately makes Radiohead sound special — not to mention tense, foreboding, cinematic, and alive.

That distinction belongs to Jonny Greenwood, the most interesting man in Radiohead. For me, this is now his band.

That is not a knock on Yorke, whose voice — judging by the bootlegs of this tour that I’ve been obsessing over — remains a remarkably pristine instrument. Okay, maybe it’s a slight knock on Yorke. I have to admit I winced when I read a 2017 Rolling Stone Radiohead profile in which Yorke wears “a bleached denim jacket with the collar popped up, a thin white T-shirt and what appear to be leather pants.” If that is what Yorke is rocking in his downtime, the difference between Radiohead and Muse isn’t quite as stark as some of us would like to believe.

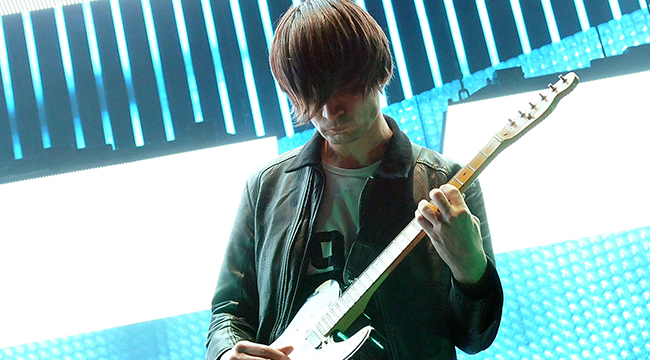

Greenwood, meanwhile, basically looks like he did in 1993: angular, handsome, severe, boyish, bookish, aloof, extremely British. He will forever be the most Radiohead-looking guy in Radiohead, which, depending on your opinion of this band, either is a compliment or an insult.

While Yorke, lamentably, took to sporting a manbun and making records with Flea after he turned 40, Greenwood remains very much the band’s dashing nerd-sage. Greenwood hangs out with Polish composer Kryzysztof Penderecki, not a Chili Pepper. He does not seem like a leather-pants person. His pastimes include designing the sampling software used to make 2011’s The King of Limbs and finding new uses for the ondes Martenot, an ancient synthesizer that’s among the many eccentric instruments that Greenwood has mastered over the years. (You can hear it in “The National Anthem” and “How To Disappear Completely,” among other tracks.)

A turning point for my appreciation of Jonny Greenwood happened in 2007. This was the year of In Rainbows, the album — even more than Kid A — that ensured Radiohead wouldn’t be remembered strictly as a ’90s band, but rather as a cross-generational institution on the level of the most iconic classic-rock bands. (In my experience, Radiohead fans who came up with the band from Pablo Honey on — like me — tend to prefer OK Computer and Kid A, whereas subsequent generations prefer In Rainbows and even Hail to the Thief. This is purely anecdotal and certainly reductive, but it seems more or less true, lining up with the albums that those respective generations encountered in their teens and early 20s.)

Two months after the release of In Rainbows, another major pop-culture event occurred: Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. One of the most acclaimed aspects of the film was Greenwood’s disquieting, soul-quaking score, in which the dread and psychological terror that had been embedded in the dystopian grooves of the past few Radiohead albums prior to In Rainbows achieved full blossom.

Rock musicians dabbling with orchestras have been a dubious proposition since at least the definitive 1984 rock satire This Is Spinal Tap, in which David St. Hubbins (Michael McKean) muses about playing “a collection of my acoustic numbers with the London Philharmonic.” At that time, the joke was on pretentious prog and metal acts like Deep Purple, the Moody Blues, and Rick Wakeman, though the classical-music bug subsequently bit esteemed singer-songwriters such as Paul McCartney, Elvis Costello, and Billy Joel. But few have made the transition as well as Greenwood, whose exemplary career as a film composer, most notably for Anderson on five films, feels like an organic, even logical extension of his work with Radiohead.

Greenwood wrote his first strings section for Radiohead on “Fake Plastic Trees,” from 1995’s The Bends, though he was already the band’s leading sonic architect in many other ways. Most crucial was his mastery of a wide range of guitar tones — from the brisk lushness of the acoustic strum in “High and Dry” to the rubbed-raw electric bombast of “Bones” — that made Radiohead instantly stand out amid a crowded field of muddy-sounding, mid-’90s grunge bands.

When Yorke bristled at following up OK Computer with another grandiose guitar-rock epic, it was Greenwood who helped to realize his partner’s vision of a new sound informed by Aphex Twin, Brian Eno, and Bitches Brew-era Miles Davis. Yorke had initially puttered away by himself on a beatbox, but “the sounds were all awful,” he later admitted in a 2012 New York Times interview. Making Kid A sound like Kid A was Greenwood’s job.

“It was good to have someone who was prepared to go out and spend money on all this wild, brand-new gear and come in and learn how to use it,” Yorke told the Times. “That really helped us along, that he was willing to go straight into that.”

For 2016’s A Moon Shaped Pool, it was impossible to hear the album and not be reminded of Greenwood’s sideline career as a classical composer — occasionally because the songs directly draw on it (such as “Burn The Witch,” which quotes Greenwood’s 2011 composition “48 Responses to Polymorphia”), but more often by how pensive, atmospheric tracks like “Daydreaming” and “The Numbers” recall the disorienting accents he applied to Blood and, later, his hypnotic score for Phantom Thread. If Yorke is Radiohead’s writer-director figure, the equivalent to P.T.A., then Greenwood is like a hybrid of cinematographer, composer, and executive producer — a supplier of mood and texture, as well as a fix-it man.

Radiohead ranks among the most musically dynamic rock bands ever, dazzling first and foremost with the deep range of evocative sounds that creep and swirl on its records. For Greenwood, who reinvented the role of the modern rock guitarist, this is his greatest legacy. Obviously Yorke’s tunes, as well as his stewardship of Radiohead, are pivotal. But when I think about what keeps me returning to this music, year after year, I find that I’m drawn to the margins, where the sounds are strangest, deepest, darkest, and most moving. This is where Jonny Greenwood lives.