How does an album that is underrated come to be properly seen, decades later, as great? How does an album become underrated in the first place? Who decides these things anyway?

To answer these questions, it’s worthwhile to ponder the story of the 11th LP by The Rolling Stones, Goats Head Soup.

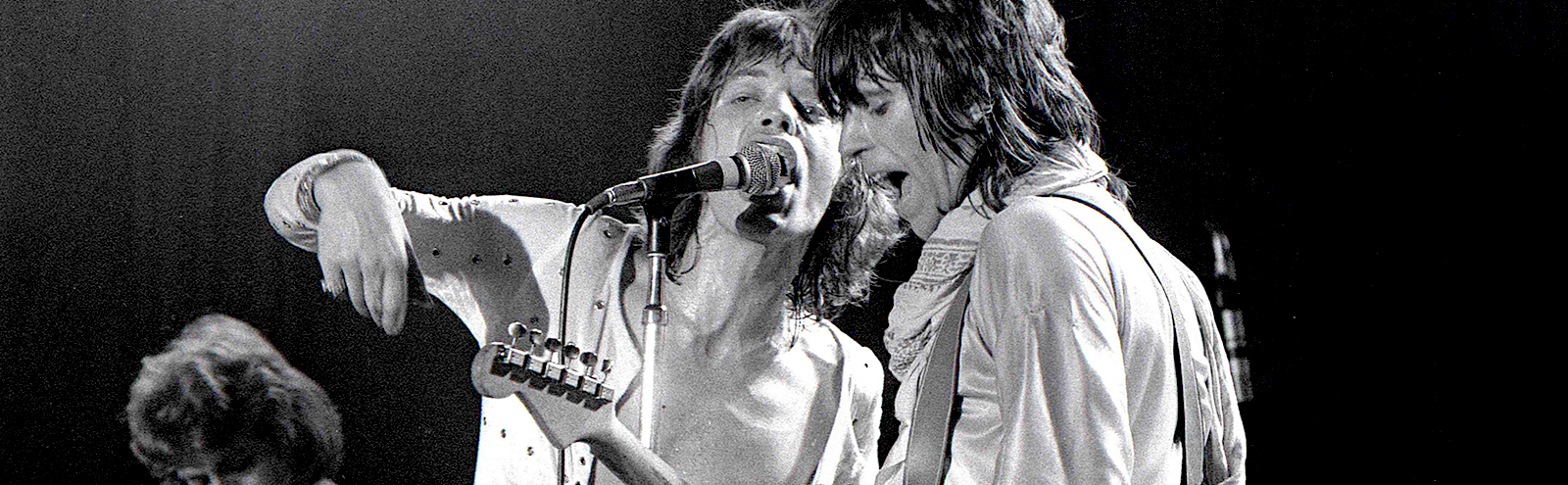

When The Rolling Stones released Goats Head Soup on August 31, 1973, it was easy to argue that it was a success. An unlikely mix of druggy funk-rock jams and sentimental ballads, it not only swiftly topped the charts in various countries around the world, it also produced a genuine international hit single, “Angie,” that crossed over into the pop space like no other Stones song in years. As a touring act, they performed two successful runs that year in Europe and along the Pacific Rim, playing for several hundred thousand people. With the possible exception of Led Zeppelin, The Stones still seemed like the biggest rock ‘n’ roll band in the world.

And yet, in spite of all those statistical signifiers, Goats Head Soup was widely perceived as not only a failure, but as a harbinger of a greater artistic decline. In the press, reviews ranged from qualified praise to open hostility. Rolling Stone gamely admitted that it had initially dismissed Exile On Main St., so the magazine was now prepared to cautiously endorse Goats Head Soup, in spite of reviewer Bud Scoppa’s only intermittent enthusiasm. “If they’ve played it safe this time, their caution has nevertheless reaped some rewards,” he wrote, in anticipation of eventually loving the album. The upstart Creem magazine was naturally more skeptical, calling Soup “future muzak” and backhandedly praising The Stones as a “perfect corporation.” In a separate pan, Creem‘s resident philosopher critic Lester Bangs sniffed, “There is a sadness about The Stones now, because they amount to such an enormous, So what?”

The implication was that The Stones were already over the hill in 1973, the year of glam and Philly Soul, and also the period during which Mick Jagger turned 30. Even critics who reviewed it positively thought of Goats Head Soup strictly as brand management, product delivered in lieu of real inspiration and invention.

When I started reading music books in the late ’80s as a budding grade-school classic-rock student, I found that Creem‘s take on Goats Head Soup had won out over Rolling Stone‘s guarded optimism. Time and again, Goats Head Soup was positioned as a sloppy and ill-considered departure point, a downward spiral from the heights of the “classic” ’68-’72 period that produced Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers, and Exile On Main St. It formed a trilogy with the band’s other mid-’70s albums, It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll and Black And Blue, as a bad stretch of road between Exile and the triumphant 1978 comeback LP, Some Girls, as The Records Best Left Ignored By Future Generations.

Even Rolling Stone came to adopt this position. In the first two editions of the Rolling Stone Record Guide, which I read religiously as a music ignorant lad, Goats Head Soup was saddled with a pitiful one-star rating, with critic Dave Marsh declaring it “a mistake, a jumble or the beginning of the end.” Around the same time, in the magazine’s comprehensive Illustrated History Of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Robert Christgau called Goats Head Soup “musicianly craft at its unheroic norm, terrific by the standards of Foghat or the Doobie Brothers but a nadir for the Rolling Stones.”

As for the band members, they also turned their noses at the poor Soup. In an interview with famous British rock journalist Nick Kent, The Stones’ longtime pianist and unofficial conscience Ian Stewart called it “bloody insipid.” Guitarist Mick Taylor — whose feelings about Goats Head Soup were perhaps tempered by not getting proper credit for co-writing one of the better tracks, “Winter” — referred to it as “not one of my favorite albums.” And then there’s Keith Richards, who has routinely badmouthed Goats Head Soup over the years, including in his iconic 2010 memoir, Life, in which he compares it unfavorably to Exile. In Keith’s view, it was a “marking-time” album crowded with too many sidemen and not quite enough Stones.

In a way, he’s right — ringers like Nicky Hopkins and Billy Preston are all over the album, whereas Bill Wyman plays on only three tracks. Also, Keith himself was slipping into a heroin coma around this time. (An alternate theory is that Exile, which is widely viewed as Keith’s album, was criticized by Mick Jagger as being unfocused, which obliged Keith to slag Goats Head Soup — a Mick album through and through — in return. When Mick years later offered his own criticism of the album, he made sure to pin it on his partner: “I mean, everyone was using drugs, Keith particularly,” he told Rolling Stone in 1995.)

In my own book, I referred to Goats Head Soup a great “bad” album, meaning I really love it in spite of its weaknesses. (Or, rather, because of its weaknesses, as listening to a band like The Stones fall apart will always be more interesting than hearing a typical band at their relatively meager best.) But now I wonder if this album really is “bad” at all, or if I simply read too many rock books telling me it was bad during my formative years. After all, whenever I put on Goats Head Soup now, it just sounds like a great “great” album. So many of the tracks stand up superbly well: “100 years Ago,” “Coming Down Again,” “Winter,” and “Star Star,” along with the hits “Angie” and “Heartbreaker (Doo Doo Doo Doo).” If Keith Richards has internalized all that criticism of Goats Head Soup, maybe I did, too.

I bring all this up because there’s a new box set coming out on Friday that attempts to rescue Goats Head Soup, once and for all, from its bad historical reputation. The case made in the liner notes — this is a “lost album” that’s “been sitting in front of you all along” — is the sort of intriguing revisionism that’s become increasingly common in the classic rock reissue market.

This expansive Goats Head Soup reissue — outfitted with the de rigueur selection of outtakes, demos, and live tracks — is part of a mini-trend of using the box-set format to reassess formerly maligned albums, a gambit that has similarly worked for the likes of Don’t Tell A Soul by The Replacements and Monster by R.E.M. If you instinctively recoil at the thought of reconsidering a record you decided long ago is garbage, it’s worth pondering how putting certain “garbage” albums in a newly reverent context can change what those albums mean, providing a new way to hear music that was formerly drowned out by so many entrenched and infinitely reiterated opinions.

In the case of Goats Head Soup, the outtakes don’t add a whole lot to the picture, as enjoyable as they are. The much-ballyhooed “Scarlet” basically is a studio jam with Jimmy Page, which (clearly) is awesome even if the song itself doesn’t amount to much. Two other previously unheard tracks, the cowbell-mad “All The Rage” and the funk-rock workout “Criss Cross,” are better if not exactly essential. For serious Stones-heads, the demos portion of the box set will disappoint for what’s not included, namely embryonic versions of tracks like “Waiting On A Friend,” “Tops,” and “Short and Curlies” that wound up on subsequent records. The Soup sessions, which commenced in November 1972 at Dynamic Sound Studios in Kingston, Jamaica — Wyman remembers their space as being “little bigger than an out-house” — were, contrary to the slovenly reputation of the album, highly productive, helping to lay the groundwork for future Stones releases over nearly a decade. But the box set’s rather stingy pick of outtakes doesn’t really reflect that.

The live album Brussels Affair, originally issued in 2011 and then taken out of circulation ahead of this box set, is another story entirely. Compiled from two shows performed during the European tour, Brussels Affair for a time was due to come out after Goats Head Soup. (When plans to add some studio cuts to the live tracks resulted in enough material for an entirely new studio LP, It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll, the live album was scuttled.) As it is now, nearly 50 years later, Brussels Affair dispels the notion that The Stones were simply on auto-pilot in 1973. On the contrary, they were still very near the peak of their powers as a live act, stretching out like never before on jammy versions of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and “Midnight Rambler” — at nearly 13 minutes, it goes on longer than even the Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! cut — while also energetically tearing into the murk of the Exile material and the funk of the Goats Head Soup songs. (Keith, as always, remained agnostic, supposedly pulling a knife on Billy Preston at one show for playing his organ too loud.) While it’s not quite as good as Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, Brussels Affair outclasses every other official Stones live LP.

But the main attraction here, as it should be, is the album itself. All these years later, Goats Head Soup benefits from not having the generational baggage that boomer critics projected on it in the moment. In 1973, The Rolling Stones were an avatar for larger cultural disappointments — if the utopian aspirations of the ’60s never came to fruition, that had to mean that The Stones were frauds, too. This idea is echoed over and over in contemporary assessments of Goats Heads Soup. It colors the assertion that this album marks the point when they became merely a “professional” band and stopped being a revolutionary one.

If that charge sounds familiar, perhaps it’s because music critics tend to eventually turn against bands who linger on into middle age. All criticism is autobiography, after all, and writing about legacy acts often reveals the insecurity that music critics have about their own relevance. But for The Stones, it was especially difficult because they were among the first rock bands ever to actually grow old. And on Goats Head Soup, specifically, they dared to sing about aging while also sounding like they were worn out. Tempos slightly lag, even on the fast songs. The keyboards and guitars blur in and out of focus. Jagger sounds either mournful or contemptuous. More than ever before, The Stones actually seem vulnerable, even fragile.

I imagine that was particularly galling for boomers, the most Peter Pan-obsessed of all generations. It was just easier to dismiss Goats Head Soup as a “safe” retreat than to contend with their super-human decadent princes staggering fearfully into adulthood. But in its own way, a song like “100 Years Ago” is risky, because Jagger admits that he’s no longer a young man and wishes he still was: “Sometimes it’s wise not to grow up,” he sighs. And yet you have no choice but to do it. Goats Head Soup is where they finally accepted this.

Everywhere you turn on Goats Head Soup, the bleakness of the grown-up world looms. The romantic ballad “Angie” is a breakup song in which true love is crushed by the logistical impracticality of incompatible lives. “Winter” uses the titular season as a metaphor for a time when “a lotta love is burned out,” likening the early ’70s to a frigid wasteland. Again, this was not a band that usually expressed any misgivings about their sins or triumphs. After the supposed moral reckoning of Altamont, they put out their two most gloriously amoral albums, Sticky Fingers and Exile On Main St. Contrast that with Goats Head Soup, which contains at least two tracks — “Coming Down Again” and “Heartbreaker” — that can be loosely described as anti-drug (or at least “drug wary”). Who could believe this? The Rolling Stones, of all bands, was sick and tired of the rock ‘n’ roll life. Even the requisite “life on the road” party jam, “Star Star,” cynically depicts backstage trysts as a series of cold, passionless transactions between the haves and wannabe haves. The song rocks, but the lyrics hardly depict a world that you would want to live in. If Exile is about raging against the dying of the light, then Goats Head Soup is simply the dying of the light.

If you grew up with The Stones in the ’60s and early ’70s, I can imagine how much of a bummer Goats Head Soup must have felt in the moment. But for those of us who came along later, and without the generational baggage, Goats Head Soup has an incredible, melancholic beauty. Yes, the band is exhausted. But the album itself is about exhaustion; they were either too honest or too tired to not foreground it. And that resonates now in 2020 more profoundly than, say, an untouchable classic made by indestructible millionaire rock stars in the south of France. For all the well-worn mythology around this band, the Goats Head Soup post-apocalyptic Rolling Stones — the band who felt old before their time, and sensed that their lives might have already peaked — feels newly, hauntingly fresh.

Goats Head Soup will be reissued on Friday via Polydor/Interscope/UMe. Get it here.