Here’s a book pitch: A sequel to Michael Azerrad’s venerable Our Band Could Be Your Life, in which the story of American indie rock’s roots in the ’80s continues by delving into the boom and bust of ’90s alternative rock.

One of the most fascinating chapters in this hypothetical tome would be about R.E.M., a subject of the original Our Band Could Be Your Life, who went from being an early pioneer of the so-called “Amerindie” scene to one of the most popular bands in the world after they signed with Warner Bros. in 1988. After concluding a successful though grueling marathon tour in support of their major-label LP, Green, R.E.M. opted to stay home for the next several years and create their lushest and most orchestrated music .

Only The Beatles had ever previously dared to essentially take themselves out of the public eye at the height of their fame, in order to focus on songwriting and honing their craft as record-makers. But with 1991’s Out Of Time and 1992’s Automatic For The People, R.E.M. somehow managed to become even more popular, selling more than eight million records combined as their artfully shot videos for folk-rock smashes like “Losing My Religion” and “Man On The Moon” played in constant rotation on MTV.

At a time when social media keeps pop stars in our faces at all times, R.E.M.’s ability to grow its audience while otherwise maintaining radio silence remains an unprecedented feat that likely won’t be duplicated. Looking back on this era more than 25 years later, R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck recalls feeling safely insulated from the ramifications of the band’s fame in the early ’90s.

“I lived in Mexico for six months after Automatic. And I was not talking to anybody, I was just hanging out. So, yeah, it wasn’t a big part of my life,” he said when reached via phone last week. “I was going through a particularly mobile two years of my life there. I had a car and a box of cassettes I listened to, and a leather jacket. And I just kind of moved around from place to place.”

Buck made himself available for a rare interview because he was promoting a new boxed set commemorating the 25th anniversary of R.E.M.’s ninth album, Monster, out today. Released in the fall of 1994, Monster proved to be the most controversial album R.E.M. ever made, as noisy, heavy-riffing, cynical, and dark as the two previous records were melodic, warm, commercial, and effervescent. The first single, “What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?,” set the album’s tone — over Buck’s gut-level, buzzsaw guitar riff, singer Michael Stipe expressed disdain for the media while affecting an ironic remove from the horror-show unfolding before him on multiple screens.

“I never understood, don’t f*ck with me, uh-huh,” he sings, with a put-upon, in-character disaffection that recalled U2’s Achtung Baby. (Though he was also no doubt also drawing on his personal angst over persistent rumors in the early ’90s that he had contracted HIV.) Like U2, R.E.M. was using satire to help ease its transition from earnest ’80s alt band to ’90s stadium rockers.

For Buck, Monster represents “a time in all of our lives that was really crazy,” when R.E.M. decided to leave the safety of their private lives behind and embrace their strange new status in the outside world.

“We had just become the fourth-biggest band in the world without really trying,” Buck said with a characteristic sardonic twinkle. “Monster is kind of confronting that.”

Of course, many people didn’t get it, and Monster stands today as the most divisive album in the band’s vaunted catalogue. The new boxed set attempts to put the album in a different light, with a battery of outtakes, a complete concert from the Monster tour, and a new remix by Scott Litt that lifts Stipe’s vocals out of the murk, highlighting the album’s penetrating character studies of outsider creeps desperate for attention and validation. While the redux doesn’t supplant the original record, it does underline Monster‘s themes more definitively. When Stipe sings, in the mechanized death-disco track “King Of Comedy,” that he’s “not commodity,” it hits with greater clarity.

Upon its release, Monster debuted at No. 1 in the US and UK, and like Out Of Time and Automatic For The People, it went quadruple platinum stateside. While initial reviews were positive, including a four-and-a-half-stars rave from Rolling Stone, the album nevertheless acquired a sour reputation among fans and critics.

Many regard Monster as the end of R.E.M.’s golden era. The distinctive red-orange cover itself became a kind of in-joke, as it became a fixture at used-CD stores from coast to coast, back when used-CD stores were still a thing. It made it easy to regard Monster as a symbol of alt-rock’s rise and fall, a bloated superstar record that was “too big too fail” in the moment and then quickly discarded in the second half of the decade as rap-rock and teen pop took over.

As someone who bought Monster the week it came out and has continued to love it for the past quarter-century, I never thought this was fair. For starters, Monster has more hits than many people remember — beyond “Kenneth,” there are future concert staples like “Strange Currencies,” “Circus Envy,” “Crush With Eyeliner,” and “Star 69.” (Those first two tracks were used brilliantly in this year’s underrated mind-bending L.A. noir, Under The Silver Lake.) But beyond the tunefulness of Monster is the record’s fascinating meta quality. It’s an arena-rock record that’s about arena rock, in which Stipe’s lyrics deal directly with how media iconography distorts and cheapens reality, set to music that both pays homage to hard rock and glam while also playing up the bombastic silliness of those genres.

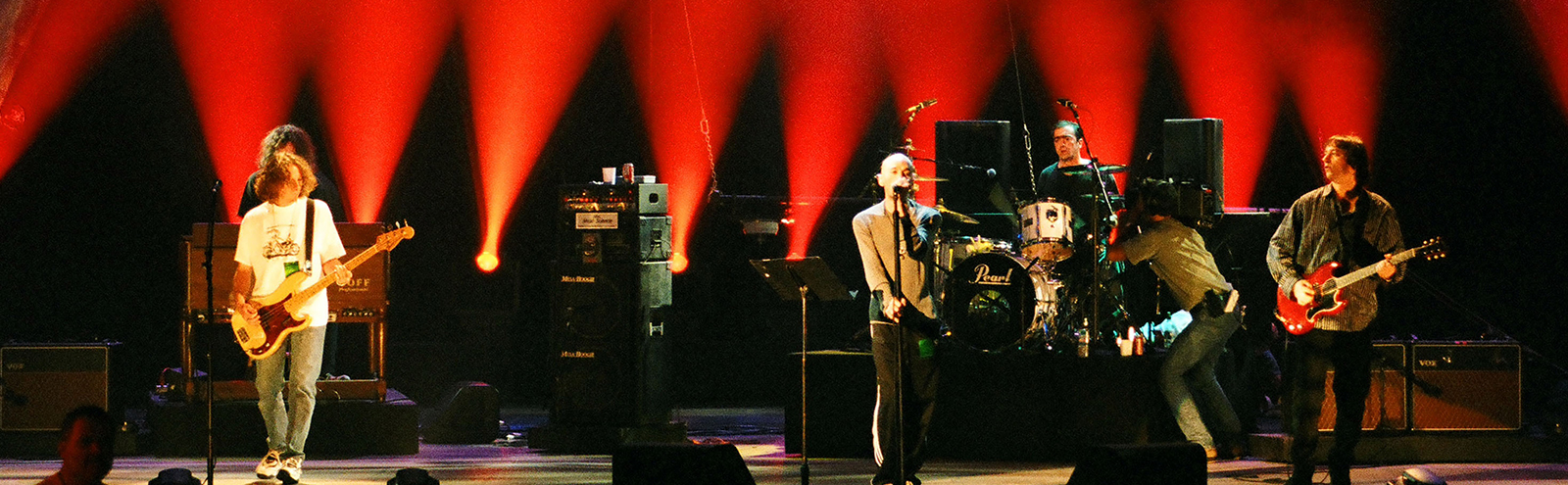

That element of R.E.M.’s Monster era comes through on the live concert recording included in the boxed set, which is culled from the band’s performance in Chicago on June 3, 1995. (Coincidentally, I saw my first and only R.E.M. concert two shows prior, in Milwaukee.) The band sounds robust and blustery, and Stipe’s between-song patter is hilariously deadpan if also inscrutable, like when he introduces “Losing My Religion” as a cover of an old hit by ’70s soft-rock singer B.J. Thomas.

In that way, Monster didn’t merely signal the end of alt-rock’s salad days, it might have even precipitated it. Clearly, R.E.M. wasn’t interested in merely perpetuating their hit-making formula from Out Of Time and Automatic. Even at the time, Monster felt like a line in the sand that fair-weather fans drawn in by “Shiny Happy People” probably weren’t going to cross.

I would liken Monster to Neil Young’s “ditch” records from the early ’70s, when he took a decisive turn toward noise and provocation in the wake of his massive success with Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young and his 1972 solo album Harvest. In that equation, Automatic For The People is R.E.M.’s Harvest, which would make Monster the band’s Time Fades Away, and 1996’s New Adventures In Hi-Fi — an exhausted, evocative travelogue written and recorded on the Monster tour that’s a personal favorite of Stipe’s and Buck’s — their Tonight’s The Tonight.

When I mentioned this analogy to Buck, he was flattered – he naturally loves Time Fades Away and Tonight’s The Night — though he denies that R.E.M.’s motivations were purely reactionary.

“I think one of the things that we were subconsciously thinking was, it’s better not to be pinned down. Like, there’s those guys who do that,” he said. “Automatic‘s a great record, but you don’t want to make the same record twice and have the second one be less good or just wear out your welcome.”

To elaborate on this point, Buck made a surprising pivot to … Beyoncé. “I think with popularity, you should use it to try things. Beyoncé’s a great example of that,” he said. “She’s really pushing the boundaries in every way. Where she could still be doing Destiny’s Child, playing Vegas six nights a week.”

The road to Monster goes back to the start of 1993, when R.E.M. held a band summit in which they mapped out their next few years. The centerpiece was a massive world tour of sheds and stadiums scheduled many months in advance. Buck also envisioned a record that R.E.M. would write and record while on the road, the band’s 10th. In the meantime, however, they had to make their ninth LP.

As that record took shape, R.E.M. focused on becoming a road-ready unit again. Buck, who had pushed the band to strip down and eschew electric guitars on the previous two albums, was now looking to the swaggering punk records he loved as a teenager, like The Stooges’ Fun House, for inspiration. Lots of simple riffs with minimal nuance. (“There must be minor chords on that record but I don’t remember any,” he says.) In Atlanta, they rented a soundstage and performed their new songs every day as they would a concert set.

But as work on Monster wore on, they were stressed by the pressure of completing the album in time for the upcoming tour. And then there was the natural drift that occurs when the members of very rich rock band no longer move in the same social circles. Both factors made the making of Monster a fraught process.

“In the ’80s, the only thing we did was make music and write songs. And it just seemed like we would write 12 songs and that would be the album. In the ’90s it kind of changed,” Buck reflected. “We had more time to ourselves, so we were writing a ton of stuff. Which means Michael didn’t finish it all. So he would be presented with 30 pieces of music rather than 12. And it made the process a little longer.”

I then bought up a Rolling Stone article I remembered reading as an anxious 17-year-old R.E.M. fanatic, which suggested that R.E.M. came close to breaking up during the Monster sessions. Was that true? “We basically almost broke up a whole bunch of times, I think all bands do, you know?” he countered. “It’s hard to go from being a young person who knows exactly what’s right to being like an older person who realizes you have to deal with people who think they are absolutely right, too. I can’t tell you how many arguments we’ve had about some pointless little thing and then six months later I’m listening to it and I can’t remember which side of the argument I was on.

“You know, it got tough at the end,” he added. “But instead of canceling the tour and going off into outer space, we just kind of did it, and then made one of our favorite records.”

Launched on January 13, 1995 in Perth, Australia, the 10-month Monster tour proved to be an even bigger turning point for R.E.M. than the album. Spanning 135 shows and multiple continents, the tour was infamously marred by health problems for Stipe, bassist Mike Mills, and drummer Bill Berry, who collapsed from a brain aneurysm that March in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Beyond these personal calamities, the members of R.E.M. also faced the weirdness of rock superstardom head-on.

“It was the first and only time honestly where people were chasing us around and screaming at us in the streets,” Buck said. “We would get to our hotel and there’d be 300 people waiting outside. And you think, ‘What the f*ck? What is this all about?’ And then Bill almost died in my arms. I still have nightmares about that. All I remember is that it was crazy.”

When R.E.M. broke up in 2011, all their remaining members — Berry exited the band in 1997 — seemed determined to leave their big-time arena-rock past behind, focusing instead on idiosyncratic projects far outside the mainstream. Buck has been the most outspoken about his dislike of the music business. When I suggested that this aversion might have originated during the Monster period, Buck gently pushed back.

“I had to listen to all this sh*t in the last six months: The demos, the album itself, the remix, the live shows. And it’s way more consistent than I originally thought. It’s a cool-sounding record, you know?” he said. “It may not be the first record I’d give to someone that didn’t know what we were all about, but I’m actually liking it better than I liked it at the time.

“It reminds me a little bit of Fables Of The Reconstruction,” he added, “where I don’t think any of us were super happy with the mixes or anything. And then years later you realize, well, it’s its own entity. We couldn’t see the mistakes or failures or whatever. That is just what it is.”