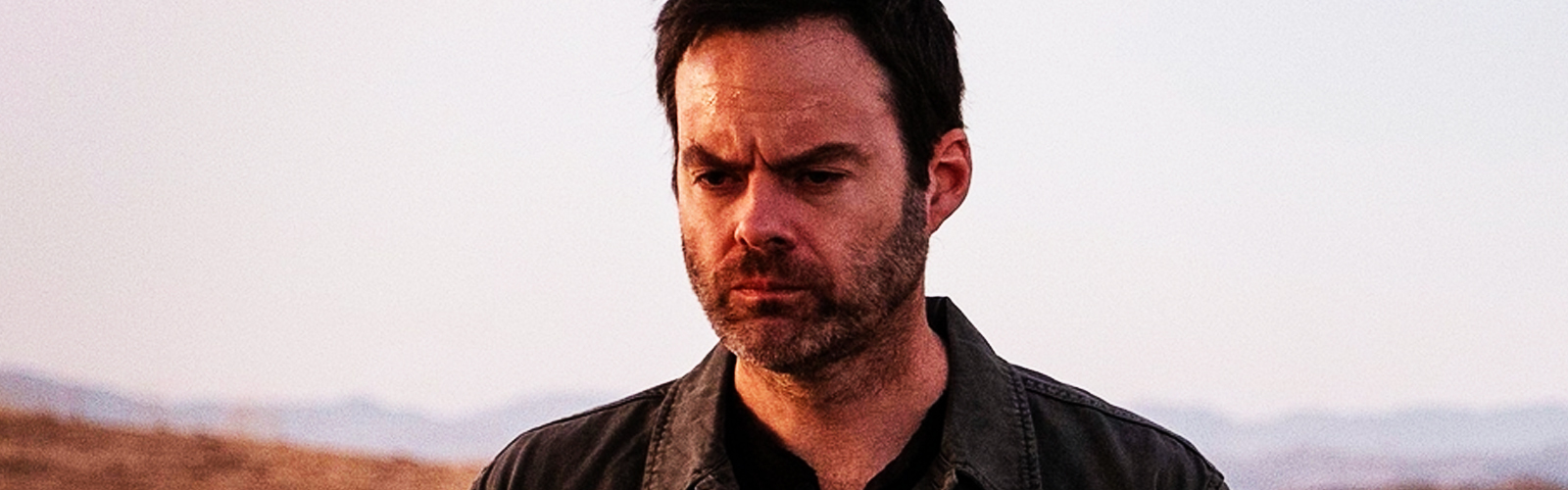

In the Barry season three finale, Barry Berkman (Bill Hader) gets on his hands and knees in the desert. He’s wailing and shaking uncontrollably, like a chihuahua who knows they just did something very wrong. It’s an oddly high-pitched tone for a grown-ass man, especially a grown-ass man who happens to be an assassin who is capable of killing mercilessly while entrenching himself in the lives of those he’s killed. Barry wails and shakes, even harder at an even higher frequency the longer he’s on the ground. The wails turn into sobs, the kind you only do when you’re alone, except he’s cowering in front of Albert Nguyen, a Marine he saved in Afghanistan. “I know evil, Barry,” Albert says over Barry’s sobbing. “And you’re not evil.”

Barry has always been a great show with clever writing, innovative direction, and sharp performances from Hader, Sarah Goldberg, Stephen Root, fishing fanatic Henry Winkler, Anthony Carrigan, and more. These days, shows we love feel like a blur, like a dream you remember but can’t describe. Barry’s pivotal third season accomplished an impossible mission in the Peak TV era: it sticks with you. The motorcycle chase through LA in season three episode six felt more horror than action, so tense you can feel it right now. Barry’s near-death walk in episode seven, and Barry’s go-to body burial location: a remote location in the desert by a tree that could be on the cover of an alt/indie/alt album.

Barry Berkman started in a bedroom in Cleveland, Ohio. The contract killer who offers to stab targets in the nut had a plaid sheet set and a Metallica poster over his bed. He was seemingly wholesome with very violent tendencies that you might miss if you were not paying enough attention. After encountering an acting class while on a job in Los Angeles, Barry catches the acting bug, and decides to pursue his new, random dream while continuing his contract killing. A lot of television shows eventually abandon their premise as they transform. Barry has never abandoned its premise, but it has transformed it. As the story has moved forward and as its characters’ lives spiral as they get more involved in the entertainment industry, the tone of the show has darkened along with them. But it still, always, even in the darkest of moments, manages to be funny, especially thanks to performances from comedy kings Hader and Winkler.

Barry’s embarrassing but deeply pure cry in the season three finale represents everything Barry is: emotionally, even physically painful but also painfully funny. At first glance, Barry might seem similar to The Sopranos or Mad Men, the groundbreaking antihero dramas that defined the Golden Age of television and changed it forever. While neither The Sopranos nor Mad Men were necessarily empathetic to their flawed (more accurately terrible) protagonists, they provided characters to root for to provide balance (Carmella Soprano, Peggy Olson). Barry doesn’t provide that balance at all, instead allowing most of its characters, even the ones not involved or privy to the show’s violent side, to be quite terrible, self-absorbed people. Barry is also more sprawling, following storylines that, outside of this series, have nothing to do with each other, such as a streaming show and the sparring between two mobs. Barry is a comedy, a crime thriller, an unraveling of toxic masculinity, and a brutally honest satire of the entertainment industry, examining how it can change people for the worse. At the beginning of the series, Barry was a contract killer, yes, but he’s gotten even worse since he moved to LA and became an actor.

In its third season, Barry separated itself as an essential, revolutionary show that will define the next era of the medium.