Guillermo del Toro’s contributions to popular culture can’t be either overstated or underestimated. Across four decades, 11 (soon to be 12) feature films and several multi-episode series — the Tales of Arcadia trilogy, The Strain, and the recently well-received Netflix horror anthology, Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities — del Toro has bridged the once sizable gap between mainstream audiences and the horror genre through a singular mix of fairy tales, dark fantasy, and, of course, monsters in all of their grotesque beauty.

With del Toro’s latest effort, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, about to hit movie theaters and streaming, there’s no better time to look back at the director’s astonishing career and weigh in on some of his best works.

Cronos (1993)

In 1993, a then 29-year-old Guillermo del Toro ushered his first film into creation. Cronos was a supernatural/family drama where the first-time filmmaker displayed a remarkably assured command of tone, craft, and theme. The film centered on the heartfelt story of a grandfather, Jesús Gris (Federico Luppi), the unconditional love he shares with his preteen granddaughter, Aurora (Tamara Shanath), a medieval, life-extending device, and the machinations of an aging multimillionaire, Dieter de la Guardia (Claudio Brook), and his boorish fail-son, Angel (Ron Perlman, del Toro’s soon-to-be frequent muse). Dying and desperate, the elder de la Guardia attempts to obtain the one object his wealth can’t buy (i.e., more life) by any means necessary. Combined with stunningly repulsive practical effects, shot through with existential humor, and layered thematically, Cronos was more than just a promise of things to come. It was a promise already fulfilled.

Mimic (1997)

Mimic, del Toro’s first film shot in the U.S. with an all-English-language cast, was hampered by rumors of studio interference that marred the filmmaker’s vision and a story focused on a new species of human-sized insects hellbent on expanding their territory up from the sewers to the city streets. Setting a precedent hinted at in Cronos, no one, not even the most innocent child, is safe from the ravenous monsters that dwell in the dark subterranean spaces underneath the city here.

Capable of cleverly camouflaging themselves to appear human-like from a distance, del Toro’s creations played on our instinctive fears of the non-human and the natural world turning against us. With influences ranging from the oversized radioactive horrors of the 1950s to the timely eco-horrors of the 1970s, Mimic remains an essential, if flawed, entry in del Toro’s filmography.

Blade II (2002)

The rare sequel that improves on its predecessor on practically every level, Blade II borrows inspiration from James Cameron’s Aliens with an extended ambush sequence set in the dank, dark underground sewers of a city. The sequence pits a group of non-traditional, cooler-than-cool vampire hunters (they’re both vampires and hunters) against a ravenous swarm of feral mutant vampires. The vampire-hunters have all kinds of high-tech weapons on their side, the feral mutants just their distended jaws, physical strength, and cunning. Not surprisingly, the vampire-hunters — Blade and one or two others excepted — don’t stand a chance, underscoring a key idea explored in Blade II, the hubris of current-gen vampires, and their likely fall when confronted with a new apex predator. With a katana-wielding Snipes as the laconic, stoic title character, pre-MCU comic-book adaptations simply don’t get any better.

The Devil’s Backbone (2001)

Del Toro’s subsequent film, the Spanish-language The Devil’s Backbone (“El Espinazo del Diablo”) foregrounds one of his lifelong obsessions, the Spanish Civil War that left the Francoists — fascists and authoritarians by another name — in power over all of Spain for more than four decades. Set at an orphanage for boys during that period, The Devil’s Backbone nominally follows the newest addition, Carlos (Fernando Tielve) a young boy unceremoniously dropped off by friends of his father, an anti-Francoist Republican. While they depart, embracing all but certain death on the losing side of a war, Carlos quickly befriends several of the other boys. Before long, however, a vision of a dying or dead boy, Santi (Junio Valverde) begins to haunt Carlos.

Despite the ghost story trappings, del Toro isn’t interested in the usual jump scares associated with the sub-genre, choosing instead to go deeper while examining the shape and nature of trauma and how it can not only affect multiple generations but warp the minds of survivors too. Heavy on symbolism, The Devil’s Backbone might just be del Toro’s most lyrical, poetic work and a clear masterpiece.

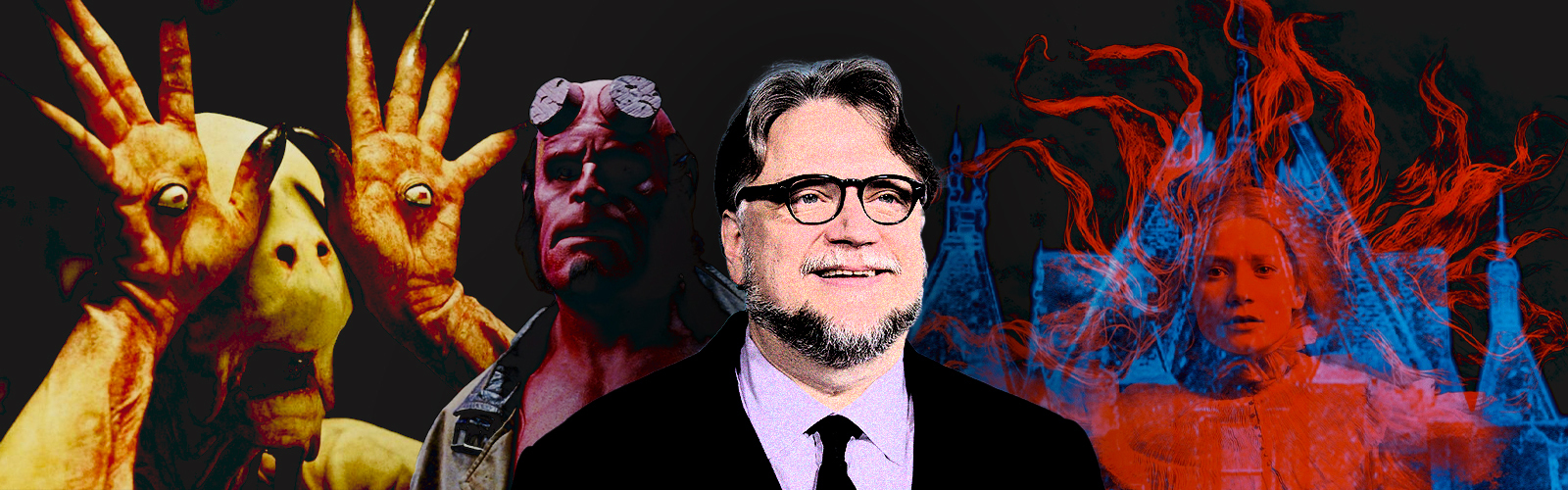

Hellboy (2004) / Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008)

Returning to the comic book movie genre, del Toro teamed up with artist-writer Mike Mignola, the creator of Hellboy, and Perlman, as the title character. The spawn of demons brought into our world to destroy it, Hellboy instead becomes a superhero, thanks to the unconditional love and acceptance from his adopted father, Professor Trevor Bruttenholm (John Hurt), and the Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense (B.P.R.D.). A cigar-smoking, wisecracking, cat-lover, Hellboy carries a big fist (literally) but has an equally big heart as he pushes back against the forces of evil and their attempts to usher in the apocalypse.

It’s easy to see what brought del Toro to Mignola’s Hell-born character: Hellboy represents an irresistible trope, the misunderstood monster, feared and sometimes hated for their otherness, but who never lets prejudice or bias dictate his actions: Even when he kvetches about it, Hellboy always does the right thing. Which, in Hellboy’s case, usually involves punching — lots and lots of punching.

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006)

Completing a loose trilogy that began with Cronos and continued with The Devil’s Backbone, Pan’s Labyrinth finds del Toro returning to the Spanish Civil War and the authoritarian violence and brutality that followed General Francisco Franco’s victory in the war over the Republican Loyalists and their allies. For Ofelia (Ivana Baquero), a new home means a new stepfather, Captain Vidal (Sergi López), and a new half-sibling carried by her pregnant mother. Flipping the script on old-school fairy tales, Vidal stands in for the “evil stepmother” trope. Here, however, he doesn’t just mistreat Ofelia and her mother. He’s a mini-dictator, butchering one-time Francoist opponents, real or imagined, with virtual impunity. Of the many monsters wearing human faces in del Toro’s filmography, Vidal represents the most terrifying, in large part because there’s nothing exaggerated or hyperbolic about him. He’s fascism distilled into a pure malevolent presence and Ofelia is his exact opposite, innocent, naive, and desperate to escape a stifling, suffocating existence.

She does this via a set of magnificently interwoven scenes set in a beautiful, beautifully dangerous world filled with fairy tale characters, some benevolent, some, like her stepfather, malevolent, and others, like in the real world, ambiguous in their intentions and actions. Pan’s Labyrinth builds to a memorably bittersweet ending, suggesting an escape into fantasy and fiction might be preferable to a life of repression and oppression.

Pacific Rim (2013)

Before the MonsterVerse was a gleam in a producer’s eye, del Toro stepped into the kaiju space, pitting human-powered robots (mechas) against fearsome, Tojo-inspired monsters from the literal deep. As with most kaiju entries, human characters and their petty, interpersonal concerns take a back seat to rollicking wrestling matches between del Toro’s monsters and robots. While the inspirations are obvious — anime and Tojo, respectively — del Toro brings his customary obsession with detail. Everything from the suits the human pilots wear to the interiors of their individual cockpits, the battle-scarred, multi-functional giant robots (Jaegers), and the seemingly endless series of monsters are richly rendered. If nothing else, Pacific Rim represents del Toro at his most childlike, revisiting the animated robots and man-in-suit monsters of his youth, an innocent preteen with a hyperactive imagination playing with his favorite toys, albeit computer-generated toys and a $200 million-dollar budget.

Crimson Peak (2015)

Misunderstood and dismissed on its release seven years ago, Crimson Peak, a sumptuously made gothic romance, deserves critical reevaluation. The supposed central mystery wasn’t, in fact, much of a mystery (frustrating some), while the horror, such as it was, revealed a del Toro uninterested in the usual mechanics of the genre, instead, focusing on set pieces structured around the central character, Edith Cushing. Mia Wasikowska plays the young heiress and wannabe novelist at the dawn of the 20th century who becomes fatally entangled with a fortune-hunting brother-and-sister couple, Thomas (Tom Hiddleston) and Lucille Sharpe (Jessica Chastain).

The supernatural inevitably make a forceful, permanent appearance, but like The Devil’s Backbone, the ghosts in Crimson Peak are less a frightening presence or menace than the embodiment of history, trauma, and grief. Here, the ghosts also function as both observers and participants, warning Edith of Lucille and Thomas’s duplicitous motives and their plans for a future that doesn’t include her except as a distant, fading memory.

The Shape of Water (2017)

With 2017’s The Shape of Water, del Toro joined longtime friends Alfonso Cuarón (Gravity) and Alejandro G. Iñárritu (The Revenant, Birdman) as Mexican-born Best Director winners. The Shape of Water returned del Toro to one of his foundational obsessions, Universal Monsters (specifically the Gill-Man), grafting the unnamed and captive water dweller (Doug Jones) with an ambitiously layered Cold War allegory and an unlikely, if nonetheless poignant, romance between the kidnapped amphibian and a mute cleaner, Elisa Esposito (Sally Hawkins). Here del Toro seemingly does the impossible, transporting audiences to a half-fictional, half-real past to present a cautionary tale about how governments, regardless of their stated political ideology, suppress what they don’t understand and exploit what they do, often with the best of intentions and the worst results.

Nightmare Alley (2021)

Not a horror film per se, del Toro’s most recent work, Nightmare Alley — an ultra-stylish adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 critique of class, capitalism, and carnival life — finds del Toro indulging his obsession with the cynical, amoral, greedy takers, losers, and outsiders present in film noir, an indifferent universe, and the hellish consequences that follow when they try to change their socio-economic position. Nightmare Alley centers on Stan Carlisle (Bradley Cooper), a carnival worker-turned-celebrity-medium with insatiable appetites. A moral black hole, Carlisle sees himself as naturally superior to the marks he manipulates for personal gain. Unfortunately for Carlisle, he doesn’t realize he’s in a noir and that Dr. Lilith Ritter (Cate Blanchett), a psychiatrist to the city‘s elite, is the most fatal of femme fatales. Like (or better than) Carlisle, she’s an expert manipulator. Probably the bleakest film in del Toro’s filmography, Nightmare Alley proves — as if any additional proof is needed— that del Toro prefers the company of fictional, fantastical monsters to the reality of human-made ones.

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)

A longtime passion project, del Toro’s version of the classic tale utilizes a mix of old-school, stop-motion animation techniques and modern technology. A-level talent comprises the voice cast, including Ewan McGregor as the voice of Sebastian J. Cricket, David Bradley as the voice of Geppetto, Tilda Swinton as the Wood Sprite who brings Geppetto’s creation to life, and longtime del Toro regular Ron Perlman in a small, but possibly pivotal role, as Podesta, a fascistic government official. Del Toro and his collaborators promise to take the familiar story of Pinocchio into the kind of monster-filled dark fantasy that has become a hallmark of del Toro’s career as a filmmaker.