Earlier this month, Elton John played the last date of his five-year, 330-show “Farewell Yellow Brick Road” tour. The concert took place in Stockholm, and the 76-year-old was reportedly emotional as he bid adieu. Though he also hinted that this might not actually be the end of his live performance career. Maybe in the future he will do the occasional one-off show or even a residency in a place like London or Las Vegas. After all, this tour made just under $940 million, the highest grosser of all-time, at least until Taylor Swift concludes her Eras tour. Even after all these years, the demand is still there for more Elton.

Frankly, it’s hard to imagine Elton John stopping, and not only because of that hefty haul. Well into his senior years, he bragged about playing more than 100 shows a year, the result of a tireless work ethic that started during his teen years when he would knock out “Danny Boy” for drunks in local pubs. At home, he obsessively collected records and studied the sales charts. His penchant for memorizing statistics continued into adulthood, as the name Elton John came to dominate those very same charts. Over the course of many decades, he always seemed to find a way to get back to the top. When you have played the game as long as Elton has, and as successfully, how can you just walk away?

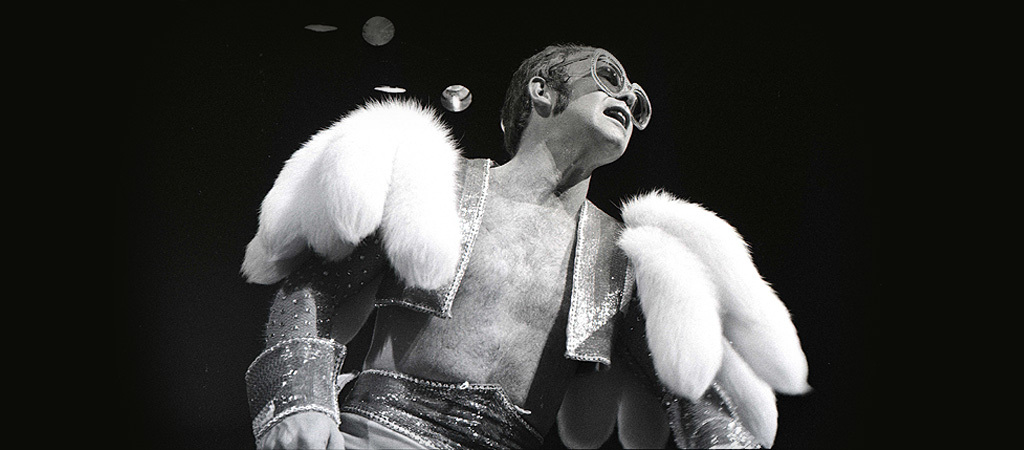

In light of Elton’s retirement — or perhaps semi retirement — it seems appropriate to look back on his career and follow his path from lonely adolescent music nerd to internationally famous superstar. A man whose gift for melody is rivaled in the world of rock only by the likes of Paul McCartney and Brian Wilson, Elton is also a style icon and one of the first openly gay rockers ever, ever since he came out to Rolling Stone in 1976 during a stridently macho era.

Here are my top 50 favorite Elton John songs. It seems to me he lived his life like a … well, you know the rest.

PRE-LIST ENTERTAINMENT: THE TELEPRESS CONFERENCE FOR THE FOX (1981)

Spoiler alert: There is nothing from The Fox on this list. For those who go deep with Elton, this may or may not register as a disappointment. (For the other 98 percent of you, I assume this is the first time you have been made aware of an Elton John album named after an omnivorous mammal.) His early ’80s debut with Geffen Records — released years before David Geffen finally ditched the superstar pals from the previous decade that he originally banked on and proceeded to make millions with scruffy Gen-Xers like Guns N’ Roses and Nirvana — has its partisans. But generally it’s lumped in with the scores of forgettable albums he released in the gaping wilderness period between 1976 and his Lion King-assisted resurgence in the mid-’90s.

I am, however, including this promotional video for The Fox, as it conveniently captures a lot of what I love about Elton John. First, some background: Before the album’s release, Geffen set up this “telepress conference” presumably for media and retailers. The idea was to drum up excitement for Elton’s 15th studio LP, which the singer-songwriter admits early on his “not my best” record while nevertheless insisting, not quite convincingly, that it does contain a certain “spark.” To get this “spark” across, a long-form commercial was presented to the public in the mode of a low-rent talk show hosted by Elton and guested by his handsome and deeply tanned lyricist Bernie Taupin, plus a cadre of extremely hairy and palpably sweaty record-label execs. The result is a fascinating time capsule of a period in the music industry when there were limitless budgets for every extravagance save for razors.

You learn three important things about Elton John from watching the approximately 49-minute clip. One, he is almost always a salesman. Two, he is almost always a mess. Three, he is almost always both of these things at the same time. This very combination of pop professionalism and personal calamity has helped keep Elton in the public eye for more than 50 years. He’s the most consistent, and most consistently inconsistent, man in show business.

By the nine-minute mark of this video, he has charmed you into thinking that The Fox might very well by the second coming of Tumbleweed Connection. This is also the point where he cracks open his first can of Budweiser. A second can mysteriously materializes minutes later. (Based on Elton’s demeanor, I’m guessing he downed around 27 cans of Bud before the cameras started rolling.) I recommend watching everything that happens afterward. But if by chance you don’t have endless patience for trainwreck-y album promotional rollouts from 42 years ago, please skip ahead to the 35:30 mark and enjoy Elton’s saucy “Six Flags” joke and the subsequent anecdote about a particular kind of English sausage. It’s the closest experience to a (surprisingly good natured!) booze-fueled cocaine haze you can have while sober.

50. “Sacrifice” (1989)

Flash forward to earlier this month. I am sitting by a go-kart track inside one of those indoor adventure parks that host birthday parties for pre-teens. (My son just turned 11.) While staring at my phone, I hear a vocal hook that takes me instantly back to a time when I was around my son’s age:

Cold cold heart

Hard done by you

Some things look better, baby

Just passing through

My mom loved this song. Played it endlessly on her Walkman, which I could also hear because she belted out the chorus in an off-key alto: “But it’s no sacrifice / No sacrifice / It’s no sacrifice at all.” This soft-rock ballad about marital commitment spoke to my long-divorced mother because it mirrored her recent dedication to sobriety, which was three years old at the time. The singer was on the verge of getting sober himself, though when this song was released he cut a ghostly white figure that made him appear much older than his 42 years.

Of course, the song playing at the adventure park was not the soft-rock ballad about marital commitment that I remembered from my childhood. It was “Cold Heart,” the 2021 Dua Lipa duet that incorporates “Sacrifice” along with three other ancient Elton John songs: “Rocket Man,” “Kiss The Bride,” and, oddly, the Blue Moves deep cut “Where’s The Shoorah?” A major international smash, “Cold Heart” has been streamed more than 1.5 billion times. More incredibly, it once again put Elton John at the center of the pop-music universe in the seventh decade of his recording career.

“Cold Heart” extended from a collaboration that began a decade prior between John and the Australian dance-music trio Pnau, who previously assembled new tracks from the fragments of old Elton John hits on the 2012 album Good Morning To The Night. At first, the formula seems obvious to the point of laziness — “Cold Heart” just stacks classic Elton John hooks on top of each other, like a sandwich composed of sugar, jelly, donuts, and popsicles. But nostalgia is not the primary objective; I’m guessing, for instance, that the intended audience for “Cold Heart” probably wasn’t aware of the 1989 album Sleeping With The Past. Or any of the other original Elton John tracks that it draws from. Dua Lipa’s star power aside, the song became a hit because of the strength of Elton John’s indestructible melodies.

What “Cold Heart” confirms is the central tenet of Elton’s career: No matter the prevailing cultural trends (or Elton’s age or distance from the current generation of young people) his gift for creating massively popular pop music is so profound that he can reach anyone at any time. His melodies worked for Dua Lipa just like they worked for Rod Stewart, Kiki Dee, Aretha Franklin, Kate Bush, a singing meerkat, Biz Markie, and many others. In that way, Elton John perhaps is the purest manifestation of pop music to occur in the modern era. Since the early ’70s, the man basically is pop, and will remain so until it is impossible to distill his work into yet another form of highly successful musical product. Based on recent history, that likely won’t happen until some distant millennium, when aliens and hyper-advanced AI finally get tired of “Candle In The Wind.”

49. “This Train Don’t Stop There Anymore” (2001)

In 1977, the New York Times published an insightful review of Elton John’s Greatest Hits Volume II by Stephen Holden. Like many music writers in the ’70s, Holden’s take on Elton wasn’t entirely dismissive (given his incredible popularity and even more unbelievable prolificacy, you couldn’t dismiss Elton John outright) but also not exactly complimentary. Surveying the latest compilation of Elton John’s many hits — “Philadelphia Freedom,” “Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word,” “Someone Saved My Life Tonight,” and seven others — the critic surmised that the superstar “helped to demystify rock by presenting himself as a fan whose campy stagecraft and Warholian detachment mocked its seriousness.” Holden rightly recognized Elton as the vanguard of post-1960s rockers influenced by The Beatles, The Stones, The Band, The Beach Boys, and other legends, who subsequently set about synthesizing those sounds into a kind of classic-rock pastiche for the new decade. Praising his ability “to execute dazzling demonstrations of short‐form craft,” Holden observed that Elton “reduces” the critical features of bygone ’60s rock “to hooks and compresses its energy to achieve the greatest momentum in the shortest time.”

On Greatest Hits Volume II, you can see Elton doing this literally on his glam-rock revisions of The Who’s “Pinball Wizard” and The Beatles’ “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds.” But Holden’s argument was broader than that. In essence, the New York Times suggested that Elton was to those ’60s bands what Pnau was to Elton John — he zeroed on the pleasurable parts of a familiar canon and discarded the substance. This, naturally, was a backhanded compliment, and the sort of sentiment that has haunted Elton for much of his career among those inclined to view him as an “unserious” artist.

By 2001, it might have seemed strange to see “epitome of pop” Elton John consorting with the era’s reigning enfant terrible of critically acclaimed trad rock, Ryan Adams, in the video for Adams’ “Answering Bell.” But Elton John was among the earliest examples of the fan/classicist archetype that Adams played to the hilt on his major-label debut Gold. This was underscored the previous year by Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous, which utilized “Tiny Dancer” and “Mona Lisas And Mad Hatters” in a wistful, “end of an era” manner that inspired Elton to pay homage to his early ’70s self on the 2001 album Songs From The West Coast. While much of that record fails to meet the standard of prime-era Elton, “This Train Don’t Stop There Anymore” stands alone as a very good self rip-off.

48. “One Horse Town” (1976)

Most people pinpoint Elton’s prime as 1970 to ’76, a period in which he released a staggering 10 studio albums (include two double-records), plus two live LPs and the soundtrack to an obscure British film called Friends. This is the body of work from whence future Australian dance music producers subsequently mined much of the material that composes the hits of tomorrow.

The 1976 double LP Blue Moves marks the end of this golden age. As the title suggests, Blue Moves is a downer. Elton was unhappy, as was his lyricist and best buddy Bernie. The endless pressure to keep their hit machine humming had finally exhausted them. Their reaction was to make the sort of “career suicide” record that all hit-making classic-rockers eventually felt compelled to create. Blue Moves alternates whacked-out prog-rock indulgences (like the self-explanatory instrumental “Theme From A Non-Existent TV Series”) with loads of self-pitying ballads about the soul-deadening side effects of show-business success (the equally self-explanatory “If There’s A God In Heaven (What’s He Waiting For?”)).

Blue Moves is unquestionably the most interesting Elton John album — it even has its own 33 1/3 book — which means it’s easy to talk yourself into thinking that it’s better than it actually is. I’m still trying to convince myself that Blue Moves is a “secret masterpiece” rather than a “fascinating misfire,” but the latter designation truly seems more accurate. Nevertheless, I really do enjoy immersing myself in Elton and Bernie’s burned-out misery, particularly the self-hating prog of “One Horse Town.”

47. “Street Kids” (1975)

You know what happens when you produce 10 albums in six years? You end up with a lot of spotty records. The closest Elton John album to perfect is 1970’s Tumbleweed Connection, which arrived early in this run. Otherwise, even the best Elton records pack in a lot of chaff. By 1975’s Rock Of The Westies, his quality-to-crap batting average rested at about .500. Two of the hits from this album, “Island Girl” and “Grow Some Funk Of Your Own,” can be charitably described as “enjoyable garbage.” I will, however, stump for this hard-rocking deep cut with a cool guitar lick that reminds me of the riffs from “Free” by Phish and “Where The Devil Don’t Stay” by Drive-By Truckers, two very different songs by two very different bands who nevertheless (I would wager) spent time listening to Rock Of The Westies at some point in their teen years.

46. “I’ve Seen The Saucers” (1974)

From Caribou, an album recorded high in the Colorado Rockies in the winter of 1974, at a rustic studio/rock star pleasure camp owned by the producer and manager of the band Chicago. Somehow, the snow piled higher inside the studio than outside. By all accounts, Elton and Bernie arrived with only scraps of songs that they were forced to whip into shape during an insanely tight production window that lasted little more than a week. That’s an impossible schedule even before you factor in all of the cocaine flying into any and all nearby nostrils during the writing and recording process. (It also explains the existence of “Solar Prestige A Gammon,” a deliberate exercise in wanton gibberish that Elton later blamed on his own arrogance in the wake of 1973’s mega-selling Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.) But since this is the ’70s we’re talking about, sometimes the excess paid off, as it does on this loopy rocker about seeing UFOs that might in fact by chemical-addled delusions.

45. “Border Song” (1970)

In that 1977 New York Times article, Stephen Holden singles out Bernie Taupin’s lyrics for criticism. After musing that Taupin’s words and John’s music “propose a similar mediation between traditional song mill values and loftier self-expression,” he concludes that the lyrics ultimately detract from the melodies because they “too frequently confuse the profound with the obscure.” Perhaps Holden was thinking about “Take Me To The Pilot,” the rousing gospel-rock number that makes no goddamn sense whatsoever. (“Through a glass eye your throne / is the one danger zone” will melt your brain if you think about for longer than three seconds.)

What Holden doesn’t consider is how Taupin contributed to that “Warholian detachment” from classic rock seriousness on Elton’s records. Not in an intentional way, as Bernie frowned on how Elton’s outrageous stage get-ups overshadowed the artfulness of their songs. But unintentionally, Bernie’s distance and outright ignorance of the subjects he most enjoyed writing about — the American West, iconic outsiders crushed by the system (like Marilyn Monroe), those tough-as-nails “street kids” — made the case for the inauthentic authenticity that Elton personified.

Taupin dared to write stirring odes to Americana like “Border Song” before even setting foot in America. In truth, Bernie Taupin was no more removed from the experience of “real” America than Robbie Robertson. But at least Robbie had Levon Helm in his band. And he also dressed the part. Elton and Bernie meanwhile were two kids from England, one of whom hated westerns (Elton) while the other gleaned much of his knowledge about the West from the romantic outlaw country songs of Marty Robbins (Taupin). Neither of them bothered to hide the fact that their brand of Americana was anything other than a fantasy. If they had tried to hide it, nobody would have believed them anyway. But their forthright fakery proved that authentic authenticity was unnecessary so long as your tunes worked. This, obviously, was hugely influential for countless artists who followed them.

44. “Love Song” (1970)

Tumbleweed Connection is the pinnacle of Elton and Bernie’s initial Americana guise, and Side 2 of that album is probably the greatest LP side in their entire catalogue. We have plenty of more tracks ahead of us to discuss, but for now “Love Song” must be highlighted as one of the only tunes on this list to not center the piano. A true act of Piano Man apostasy, it’s Elton’s “Matter Of Trust.”

43. “Talking Old Soldiers” (1970)

Robertson and his compatriots in The Band were apparently so taken with Tumbleweed Connection (as well as Elton’s famously explosively live show circa 1970) that they asked Elton to write a song for their next album. You can understand why by listening to the album’s penultimate track, which plays like a more melodramatic (if that’s possible) variation on the “tired old southern solider” themes of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” Elton isn’t the singer that Levon Helm is, though that’s hardly an insult. (I can’t wear a scarf as well as Stevie Nicks – we all have our shortcomings.) But this otherwise is one of his gutsiest vocal performances, in which he fully sells the pathos of Bernie’s lyric about a shellshocked fighter drinking his life away in a lonely bar.

42. “Holiday Inn” (1971)

This song’s subject matter was more personally familiar to Elton and Bernie: “Slow down, Joe, I’m a rock-and-roll man / I’ve twiddled my thumbs in a dozen odd bands / And you ain’t seen nothing ’til you’ve been / In a motel, baby, like the Holiday Inn.” Situated on Side Two of 1971’s Madman Across The Water, “Holiday Inn” is a snapshot of their lives right before they became mega superstars, at a time when staying in a Holiday Inn really was an exotic indulgence.

41. “Rock Me When He’s Gone” (1971)

Elton John became a star in America first, after the twin shot of his 1970 self-titled LP and Tumbleweed Connection and the corresponding raves that his early stateside tours garnered. In his home country, however, Madman Across The Water was the one that broke through, thanks to poppier numbers like “Tiny Dancer” and “Levon.” In the U.S., Madman was criticized in some quarters as overblown and bombastic in comparison to its predecessors. But what those writers were mostly annoyed by were the orchestral arrangements by Paul Buckmaster, an eccentric genius who supplied grand Wagnerian flourishes to Elton’s delicate ballads. Personally, I think those critics are wrong — Buckmaster’s strings put a distinctive stamp on many of Elton’s best early tunes. But I can also appreciate the minimalism of this Madman era B-side, a rollicking, church-y number that didn’t fit the moody vibe of the album but nonetheless feels like an unfairly buried lost classic.

40. “The Bitch Is Back” (1974)

The lead-off track from Caribou, and another example of Elton John making copious cocaine consumption work in his favor. In one verse he says, hilariously, that “I get high in the evening sniffing pots of glue.” Then in the chorus, he disingenuously insists that he’s “stone-cold sober, as a matter of fact.” Robert Christgau once claimed that Rock Of The Westies was the best Rolling Stones album between Exile On Main Street and Some Girls, but “The Bitch Is Back” (along with the album’s overall delectable decadence) makes me want to argue that it’s actually Caribou.

39. “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” (1976)

The most intriguing aspect of the Elton John/Bernie Taupin partnership is Elton’s claim that he almost never writes music in advance. Instead, he glances at Bernie’s lyrics, and then spontaneously comes up with melodies based on how the words move him. In the ’70s, that meant he was able to write a song like “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” in minutes. This suggests that Elton has a near-supernatural connection with his lyricist. Or maybe Bernie just knows what Elton likes.

An underrated attribute of Taupin’s lyrics was his ability to accommodate Elton’s sensibility as much as his own. The campiness of “The Bitch Is Back” is just one example of the straight Bernie putting himself in the platform shoes of his songwriting partner. But Bernie had his limits, and this song was the rubicon. “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” is a rare example of Elton coming up with the music first, and then asking Bernie to contribute words. They wrote it under the pseudonyms Ann Orson (Elton) and Carte Blanche (Bernie), and pitched it to Dusty Springfield. When she declined, Elton decided to record it with Kiki Dee over Bernie’s “profound misgivings,” according to Elton in his very funny memoir Me.

38. “Grey Seal” (1973)

Bernie’s issue, I assume, has to do with the extreme corniness of “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart.” At the time, it must have seemed like one of their most disposable hits, though the passage of time has disproven that. I like “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” in the same way that I appreciate Three’s Company — as an extremely ’70s slice of sunny utopianism that evokes my earliest childhood memories of harmlessly mindless monocultural entertainment.

Besides, if Bernie has an issue with “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart,” why does he give a pass to “Grey Seal,” a nonsensical song that Elton put on two different albums? (I’m including the one from the most popular Elton John LP, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.) As far as I can tell, “Grey Seal” is about pondering the mysteries of the universe — “I never learned why meteors were formed,” etc. — and seeking out the wisdom of a wise old pinniped. Surely, that’s more embarrassing than pledging fidelity to Kiki Dee.

37. “I Feel Like A Bullet (In The Gun Of Robert Ford)” (1975)

Elton has said that after Bernie hands him a stack of lyrics, he is immediately drawn to whichever song has the best title. As they worked on Rock Of The Westies, this must have been one of the first tunes he knocked out. The title just pops. It’s the sort of long, descriptive moniker that mall emo bands loved to utilize in the early aughts. (I wonder if Bernie was pissed that he didn’t come up with the phrase “My Chemical Romance” first.)

The title refers to the man who killed Jesse James, but this isn’t another callback to Tumbleweed Connection. Instead, it’s an unusual break-up song sung from the perspective of the person doing the dumping. “And if looks could kill then I’d be a dead man / Your friends and mine don’t call no more / Hell, I thought it was best but now I feel branded / Breaking up’s sometimes like breaking the law.”

36. “Empty Garden” (1982)

Elton and Bernie’s tribute to John Lennon in the wake of his murder. Elton and Lennon were bros in the ’70s, though if John had lived, it’s likely they would have feuded at some point. In terms of rock-star friendships, Elton seems like one of the best hangs. But he’s also the sort of pal who will absolutely talk smack about you publicly. Smack talk is the basis of his famously catty friendship with Rod Stewart, though (I think?) that’s mostly an act. But it’s not all an act. Elton was so annoyed by Rod’s snarky comments about his farewell tour that he wrote a bonus chapter for the paperback version of Me just to refute them.

In the original version of Me, Elton also dishes about Billy Joel’s on-tour boozing, including a story about Billy literally falling asleep at the piano one night while playing “Piano Man.” Unfortunately for Elton, Billy Joel is even surlier than he is, and the book ruptured their Piano Dude alliance.

There are more Elton rock-star feuds to discuss, but let’s pace ourselves.

35. “Writing” (1975)

The one friend with whom Elton has not feuded is Bernie. The fact that they never work together in person has no doubt helped. But the durability of their union is the backbone of Elton’s career, and it marks a sizable portion of his mythology. Elton and Bernie shaped that mythology themselves on one of their best albums, 1975’s Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy, an autobiographical work that traces the arc of their creative partnership. This song is the most literal description of their shared artistic life, capturing both their anxiety (“Will the things we wrote today / Sound as good tomorrow”) and resolve (“We will still be writing / In approaching years / Stifling yawns on Sundays / As the weekends disappear”).

34. “Ticking” (1975)

One of the weirdest Elton songs of the ’70s. Bernie’s lyric is about a man who snaps and kills more than a dozen people in a New York City bar. Elton sets that narrative to a rambling piano part that he bashes out for more than seven minutes without any other instrumental support. It’s a riveting performance that teeters constantly on the brink of complete collapse, which is actually a pretty faithful interpretation of the words. The resulting song feels like it should have been a B-side, but Elton instead stuck it at the end of Caribou, almost like he didn’t know what to do with it. To my surprise, he played “Ticking” live 177 times from 1974 to 2009. I assumed it was the kind of number that you play once and then hide like a poison pill immediately after “Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me.”

33. “Harmony” (1973)

From here on out, we are going to be seeing a lot of songs from Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. It’s my favorite Elton John album, and it’s one of my favorite double-albums ever. And that’s an important distinction, as I am a big fan of double-albums. The knock on double-albums from people who don’t like them is that they inevitably include tracks that don’t need to be there. In the case of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, you could easily point to, say, “Jamaica Jerk-Off” as a song that the world did not need to hear. However, I find that the existence of that silly reggae pastiche only makes an undeniable banger like “Harmony” sound all the sweeter. I need “Jamaica Jerk-Off.” “Jamaica Jerk-Off” completes me.

(While I could not in good conscience put “Jamaica Jerk-Off” on this list, I really enjoy typing the words “Jamaica Jerk-Off,” which is why I just wrote more about “Jamaica Jerk-Off” than the song I did include on the list.)

32. “Tower Of Babel” (1975)

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is followed closely on my list of top Elton John albums by Tumbleweed Connection and Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy. Whereas the advantage of Yellow Brick Road is its unapologetic sprawl — in terms of both themes and musical styles — the other two records are much more focused as song cycles in which the tracks coalesce into coherent statements. On Captain Fantastic, “Tower Of Babel” follows the epic title track and comments on the lecherous state of the music industry as it stood in 1975 aka the absolute peak of lecherousness in the music industry. “It’s party time for the guys in the tower of Babel / Sodom meet Gomorrah, Cain meet Abel / Have a ball y’all / See the letches crawl / With the call girls under the table / Watch them dig their graves / ‘Cause Jesus don’t save the guys / In the tower of Babel.”

31. “I Guess That’s Why They Call It The Blues” (1983)

After The Fox, 1983’s Too Low For Zero was a bright spot for Elton in the ’80s. It spawned two of his greatest singles of the era, “I’m Still Standing” and this song. My relationship with “I Guess That’s Why They Call It The Blues” formed a little later, though, when I became a pre-teen devotee of VH1 Classic in the late ’80s. VH1 Classic played this video every 15 minutes, and that exposure permanently implanted it on my psyche. I’m not saying this was a good thing, just that it was definitely a thing. While the kids at my school were talking about Poison and Milli Vanilli, I harbored a secret fascination with the mid-career work of sports-jacketed boomers like Elton, Phil Collins, and Steve Winwood. Frankly, it was a lonely pursuit. But I guess that’s why they call it the blues.

30. “Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word” (1976)

The history of power balladry typically is traced back to the ’80s with bands like Journey and REO Speedwagon, who mastered the art of building from a plaintive, piano-based lament expressing profound male weakness to a crescendo of pleading vocals and wailing guitars. This song isn’t that, exactly, but it does illustrate Elton’s under-appreciated role in shaping the power-ballad formula. “What do I got to do to make you love me?” Elton asks us. “What do I got to do to make you care?” From the start, he’s begging for love, and putting that need for affection in life-or-death terms. Of course, his (and Bernie’s) problem might be that he apparently finds it extremely difficult to apologize. Is “sorry” really that hard of a word, guys?

29. “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting” (1973)

Put this in the “Street Kids” category of songs in which Elton and Bernie attempt, hilariously, to project a “tough guy” image. “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting” is one of their most overplayed anthems so … I guess it worked? How in the hell did it work? There’s a zero percent chance that these dudes appreciate the sounds of a switchblade and a motorbike to this degree. (Who do they think they are, Bon Scott and Phil Lynott?) I’m going to credit guitarist Davey Johnstone and his excellent Pete Townshend impersonation for putting this song over the top.

28. “Candle In The Wind” (1973)

Keith Richards has the funniest (and meanest) putdown of Elton generally and this song in particular: “‘His writing is limited to dead blondes.” (Elton countered with an equally funny and mean insult: “He’s pathetic, poor thing. It’s like a monkey with arthritis, trying to go on stage and look young.”) Anyway, this is a great song that none of us ever need to hear again.

27. “Madman Across The Water” (Rare Masters version, 1971)

How about another Elton feud? He also didn’t get along with David Bowie, who Elton believed always looked down on him. A lot of that stemmed from a 1975 Rolling Stone interview in which Bowie called Elton “the token queen” of rock music. In Me Elton complains about how Bowie would “always make snippy remarks about me in interviews. ‘The token queen of rock ‘n’ roll’ was the most famous one, although, in fairness, he was absolutely out of his mind on coke when he said it.” (The interview makes it clear that Elton was correct on that count.)

Here’s my theory: Maybe Bowie was just upset that Elton used his guitarist Mick Ronson on a mind-melting version of the song “Madman Across The Water” that Elton ended up not putting on the record. I know that I’m upset with Elton about this. Ronson’s guitar solo is like the one he plays on “Moonage Daydream,” only longer and shreddier. It smokes! Simply an inexcusable exclusion on Elton’s part!

26. “Roy Rogers” (1973)

“Candle In The Wind” is the most famous song from Goodbye Yellow Brick Road about pining for a symbol of lost innocence. But “Roy Rogers” is the best song from the album about that particular subject, in part because it doesn’t soft pedal how nostalgia for the past usually derives from a moment of spiritual crisis in the present:

Sometimes you dream

Sometimes it seems

There’s nothing there at all

You just seem older than yesterday

And you’re waiting for tomorrow to call

You draw to the curtains

And one things for certain

You’re cozy in your little room

The carpets all paid for god bless the TV

Let them go shoot a hole in the moon

INTERMISSION: I EXPLAIN MY EGREGIOUS OMISSIONS

Why is there no “Your Song”? Because I don’t really like it.

Why is there no “Crocodile Rock”? Because it objectively sucks.

Why are no songs from The Lion King? Because I’m not a millennial.

Back to the list.

25. “Bennie And The Jets” (1973)

My one regret about not putting “Crocodile Rock” on this list is that I don’t have an excuse to post the clip of Elton performing the song on The Muppet Show in 1978. With the possible exception of John Denver, EJ is the all-time best musician to collaborate with walking and talking felt. And this is the only context in which “Crocodile Rock” is acceptable. However, I will share Elton performing “Bennie And The Jets” — another classic that, like “Candle In The Wind,” I probably never need to hear again – with a cast of supporting Muppets.

24. “Idol” (1976)

This crushingly sad ballad from Blue Moves is supposedly about Elvis Presley as observed one year before his death. But Taupin’s acidic lyric about a fallen pop star and Elton’s torch-y, jazzy melody could have just as well applied to their own careers right as Elton’s fame and pop prominence was cresting. Decades later, it could apply to any pop career that has fallen on hard times. George Michael must have sensed that when he covered “Idol,” heartbreakingly, late in his career.

23. “Country Comfort” (1970)

Does this song count as Southern rock? Probably not, but it should. The chorus is one of Elton’s heartiest, like it’s designed to be shouted after at least three beers. Keith Urban covered it in 2004, and the redheaded country music dork from American Idol followed suit seven years later. But the best version is by Rod Stewart, who pissed off his frenemy by slightly altering the lyrics. On the plus side, he made “Country Comfort” sound as blind-drunk as it needs to be.

22. “Where To Now St. Peter” (1970)

The first track on my beloved Side 2 of Tumbleweed Connection. Great Elton vocal, plus I’m always a sucker for a guitar being put through a Leslie speaker, even if it gives this Old West tune an incongruously psychedelic, sci-fi vibe.

21. “Razor Face” (1971)

There are many ways to interpret this song. It could be about a disfigured homeless man who is looked after by a young admirer. It could be about an aging musician who’s now down on his luck and reliant on the kindness of a fan. It could be about a closeted gay man who goes cruising at a seedy truck stop. Or could be about none of those things. (Actually, let’s say it’s the third option.)

20. “Sixty Years On” (11-17-70 version, 1970)

11-17-70 is overlooked in conversations about the best live albums of all time. (I am also guilty of this.) But in terms of Elton’s career, it truly is an essential document that — as much as his albums — explains his meteoric rise to fame in the early ’70s. No matter his later image as a soft-rock balladeer who writes music for Disney films, early on in his concert career he melded melody with balls-out rock fury with the resolve of a born entertainer determined to to play The Greatest Show You Have Ever Seen. And he did this with only a piano and a hyperactive rhythm section to support him. (Is it faint praise to point out that 11/17/70 invented Ben Folds Five?) This particular song is possibly the most dramatic moment on the record. It’s almost three minutes longer than the recorded version, even though it sheds the elaborate orchestration, and that’s mostly due to Elton’s extra emoting at the climax and the small but fervent audience’s ecstatic response.

19. “Sweet Painted Lady” (1973)

Speaking to Rolling Stone before the release of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Elton singled out this number as one of the “really classy songs” that he and Bernie wrote for their new double LP. That might seem like an odd way to describe a track about a woman who’s “getting paid for being laid,” but I know what he means. At the heart of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is a trio of mid-tempo songs that represent a melodic/lyrical pinnacle for Elton and Bernie, and this is one of them. (The other two are a bit higher on the list.) The ghostly, vaguely old-timey music perfectly suits the narrative, which manages to be simultaneously romantic and depressing.

18. “I’m Still Standing” (1983)

The self-aware comeback song. This one had to be great to justify the hubris. It’s also another VH1 Classic staple, which means I likely remember more about the music video than Elton does. (He famously got smashed on martinis with the members of Duran Duran during the shoot.) In retrospect, the “I’m Still Standing” video was probably my first exposure to queer cinema. Yes, there is a quick clip of Elton gently tapping a woman’s behind. (I’m guessing that a nervous record label exec insisted on a bare minimum quota of heterosexual content.) But that is quickly overshadowed by numerous shoots of muscular painted men in near-nonexistent speedos cavorting on a beach. Elton was still standing, but more important he was still subversive.

17. “My Father’s Gun” (1970)

Bob Dylan, according to Elton John in Me, praised the lyrics to “My Father’s Gun,” which closes out Side 1 of Tumbleweed Connection on an emotional high. You can almost imagine Bob hearing it and deciding to write “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” from the perspective of the father. Not that this actually happened, but you can certainly imagine it.

16. “Amoreena” (1970)

This love song dedicated to a “lusty flower” with whom the protagonist dreams about “rolling through the hay” is prominently featured, weirdly, in Sidney Lumet’s classic 1975 film Dog Day Afternoon. As a person who thinks way too much about soundtracks and how to properly pick music, this has long confounded me. If you have seen it, you know that Dog Day Afternoon ranks as one of the most iconic New York City movies ever. And New York City is a place utterly lacking in hay and lusty flowers. Surely, given the approximately 16,000 rock songs written in or about New York City, there were more appropriate options than the Old West concept record written by two Englishmen. (I imagine Lou Reed was super pissed when he saw Dog Day Afternoon and immediately heard Elton John. Though he was probably already super pissed before he walked in the theater, because being super pissed was a state of mind for Lou Reed.)

What explains the inclusion of “Amoreena” in Dog Day Afternoon? Turns out the editor Dede Allen played the song while cutting the film, and Lumet liked the song and put it in the movie. It’s that simple. I also like the song, so I put it No. 16 on my list.

15. “The Ballad Of Danny Bailey (1909-34)” (1973)

Here’s a song that’s about a fictional bank robber, which would have been a better thematic fit for Dog Day Afternoon. (This will be the last time I complain about the music supervision of a 48-year-old film.) “The Ballad Of Danny Bailey (1909-34)” is also part of the “classy” trio at the center of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, and it might be the classiest of the bunch. It’s like a Randy Newman song with 100 percent more bubblegum.

14. “Philadelphia Freedom” (1975)

Normally, I don’t like to call out colleagues working in the list-making trenches. However, I have to take issue with Rolling Stone‘s recent list of LGBTQ Anthems. Naturally, an Elton song made the list, as law requires. However, the magazine went with “I’m Still Standing” and not this song. As we have established, I am also a fan of “I’m Still Standing.” (Incredibly, that song also landed at No. 18 on their list.) However, if you can only pick one Elton John anthem for an LGBTQ list, it has to be “Philadelphia Freedom.” It’s a frothy, disco-soul tribute by Elton John to the great tennis player and cultural trailblazer Billie Jean King. Is it possible for a song to be queerer than that? As a heterosexual rock critic, I can’t claim to be the ultimate decider of that question. But I have a strong suspicion that the answer is “maybe but probably not.”

13. “Take Me To The Pilot” (1970)

I have tried to give Bernie Taupin his due as an equal-ish partner with Elton John. But when it comes to “Take Me To The Pilot,” Elton deserves extra credit for elevating one of Bernie’s most confusing lyrics. The title is pretty good, because Bernie is always good with titles. (He’s like a less fanciful Robert Pollard.) And I get the gist of what he’s saying. He wants to be taken to the pilot of your soul. Which is the brain (if you’re an intellectual, which is Bernie is not) or the heart (if you’re a romantic, which for Bernie goes without saying). The rest is an incoherent jumble of disconnected images, save for the relatively concrete “na na na na’s.” And this doesn’t matter at all, because Elton testifies his ass off while banging the hell out of the keys. His conviction, and his conviction alone, is what sells this song.

12. “Levon” (1971)

This song has a lot of the same gospel affectations as “Take Me To The Pilot,” but the lyrics are better. (It also doesn’t rock as hard, but I dig Paul Buckmaster’s spirited orchestrations.) I also appreciate that Bernie loved The Band so much that he named the song’s protagonist after Levon Helm. Clearly, this was the correct band member to single out. (Imagine if this song were called “Robbie” or “Garth.”)

11. “Tiny Dancer” (1971)

The inevitable “song I’m probably underrating because I’ve heard it too many times” track. It’s not like it was even a huge hit upon release. “Tiny Dancer” became a lot more well known after Almost Famous. And now it has a lot more baggage. I hate to be a snob but if this were still just one of many excellent and relatively obscure numbers from Madman Across The Water, it would have made the Top 10.

Having said that, “Tiny Dancer” usually affects me more than I anticipate. Even after hearing it a trillion times, I still get the chills sometimes when Elton sings, “He makes his stand / In the auditorium.” That’s also the part in the movie where the entire bus falls in and starts singing along. I am not proud of this. I am only a rock critic who is susceptible to romanticized depictions of rock critics.

10. “Daniel” (1972)

The sound of pure comfort. Whenever I hear this song, I think about being a very tiny person laying on mediocre early ’80s carpeting and staring up at the ceiling while an oldies station plays softly in the distance. I don’t know if this is an actual memory of listening to “Daniel” when I was a kid. I suspect that this frictionless embodiment of early ’70s easy-listening pop has the power to invent happy, carefree memories by virtue of Elton’s reassuring Fender Rhodes, that wondrous ARP synth lick, and the charmingly fake flute tones. Anyway, please play this on my death bed.

9. “Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy” (1975)

Elton John was so popular in the mid-’70s that he could get away with producing an album about his own rise to success. It’s hard to imagine a contemporary artist getting away with this now without it seeming madly self-absorbed. (Actually, I would love to see Lana Del Rey write an album about her Lizzie Grant years.) As good as Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy is, however, the one flaw is that the title track nails the concept so solidly that the rest of the record feels a little redundant. As self-mythology goes, this song evinces a fair amount of humility: “We’ve thrown in the towel too many times / Out for the count and when we’re down / Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy / From the end of the world to your town.”

8. “Someone Saved My Life Tonight” (1975)

More autobiography from Captain Fantastic, about the night Elton decided to end a marriage engagement in his pre-fame years. This has to be the greatest song ever written about a closeted man deciding to break off a romantic relationship with a woman. It’s also the greatest song to contain a lyrical reference to “Sugar Bear,” with all due respect to the 2000 Insane Clown Posse track “Sugar Bear.”

7. “Rocket Man” (1971)

Elton resented Bowie because Bowie thought he was cooler than Elton, and also because Bowie was right when he thought that. But we do not need Elton to be cool like we need Bowie to be cool. This is best illustrated by how each man addressed the subject of space travel. In “Space Oddity,” Bowie makes the Milky Way feel like a sexy, foreboding place to which weirdos and freaks can escape for all eternity. In “Rocket Man,” Elton contemplates the galaxy like a regular Joe Sixpack — he doesn’t even understand the science, it’s just his job five days a week. Bowie was in conversation with the heavens, but Elton is engaged with us. Which is why “Rocket Man” will always be 10 times more overplayed than “Space Oddity” ever will be.

6. “Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me” (George Michael duet version, 1991)

Elton famously hated this song when he was recording it. It’s a big ballad that’s really tough to sing, and then you factor in how he was at Caribou in the Rockies and gacked out of his freaking skull on blow. It was so difficult to get through a take that he deliberately tried to sabotage himself. (This explains the part where he sings “don’t discarrrrd me,” the single strangest vocal phrasing of his career.) Producer Gus Dudgeon ended up salvaging the song in post-production by calling up Carl Wilson and Bruce Johnston of The Beach Boys do backing harmonies. But “Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me” did not achieve full-on power ballad glory until the early ’90s, when Elton duetted with George Michael for this live-take show-stopper. Yes, they originally paired up at Live Aid, but that was a mere warm up for one of greatest ballad performances of modern times.

5. “Mona Lisas And Mad Hatters” (1972)

Contrary to the narrative about Elton distilling all of his rock influences into easily digestible hooks, “Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me” takes a while to get going, riding a slow path to the climactic chorus (or even a reference to the title). By modern pop standards, it practically drags. (Though the emotional fireworks reward your patience, obviously.) “Mona Lisas And Mad Hatters” is also like that. You could argue that the song doesn’t have a cathartic payoff at all. (Though Elton does hit the second occurrence of the line “my own seeds shall be sown, in New York City” pretty hard.) But the lyrical piano playing propels the song forward, even as Elton imbues Bernie’s introspective lyric about the shady aspects of Manhattan with appropriate sensitivity.

4. “I’ve Seen That Movie Too” (1973)

My dark horse pick. It’s the third song from that mid-album, mid-tempo trilogy from Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, and it’s the best example of Elton and Bernie working in “serious literary songwriting” mode. The device of using show-business lingo to describe the end of a loveless relationship is expertly executed by Bernie, and Elton rises to the quality of the lyric with music that conjures a mix of Sunset Boulevard and late-period Beatles. The string arrangement by Del Newman is particularly cinematic, especially when the orchestration overtakes the backward guitar solo. Just an excellent job by all involved. Plus: Axl references this song in “You Could Be Mine,” which proves that the Use Your Illusion albums were his attempt to remake Goodbye Yellow Brick Road twice.

3. “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” (1973)

Elton’s finest falsetto. (At least in the days when he still had a falsetto.) Also an instance where his “pop professional” and “personal calamity” sides fully merge. Armed with Bernie’s rueful lyric about wishing he never left his boyhood farm, Elton made “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” into a song about yearning for a simple life at the very moment when such a thing will never be possible for you ever again. Special shoutout to the live version from 1980 in Central Park, another VH1 Classic classic.

2. “Burn Down The Mission” (1970)

Everything you could possibly want from an Elton John song. It starts out as a ballad, and it’s a very pretty ballad. And then it explodes into a rocker, and it’s a very rockin’ rocker. And then it’s a ballad again, and then it’s a rocker again. I was tempted to go with the 18-minute version from 11/17/70, which segues into Elvis Presley’s “My Baby Left Me” and The Beatles’ “Get Back.” But the studio version from Tumbleweed Connection delivers just as much ammunition in one-third the running time.

1. “Funeral For A Friend/Love Lies Bleeding” (1973)

Is it questionable to put an 11-minute song at the top of a list for an artist synonymous with pop radio singles? Possibly. But it has to be done. This is Elton’s “November Rain.” It’s his Side 2 of Abbey Road. An epic scene setter for his most epic album, “Funeral For A Friend/Love Lies Bleeding” is excessive and extremely catchy. A tour-de-force that stands as his ultimate magnum opus. An expression of personal humanity that projects larger-than-life mythos. In the opening half, Elton kills and them buries himself. And then in the closing half, he is resurrected in messiah-like fashion and triumphs in undisputed arena-rock glory. Along the way, we are treated to many cool synth and guitar tones. It feels like going to Disneyland while shotgunning a bottle of champagne. Like that, 11 minutes fly by in what feels like two seconds. This yellow brick road might be long, but like Elton’s career, you don’t want it to end.