Roger Corman should need no introduction, but he does need a little bit of an explanation. Since the 1950s, Corman’s name has been synonymous with low-budget filmmaking, and both the “low-budget” and “filmmaking” halves of that description matter. Corman, now 91, has long been a savvy businessman, anticipating and drafting off filmmaking trends and delivering product that fits the public’s desires at a cost that makes it unlikely he or anyone around him will lose money. (There’s a reason he wrote a book titled How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime.) But he’s also very much a filmmaker and, as a director and producer, his taste helped change the direction of American film several times over.

Early in his career, Corman directed everything from Westerns to monster movies, but he started to come into his own as an artist in as the ’50s turned into the ’60s. Working, quickly, from inspired scripts by Charles B. Griffith, Corman made the dark horror comedies A Bucket of Blood and Little Shop of Horrors. He also embarked on a lush cycle of horror films (mostly) inspired by Edgar Allan Poe and frequently starring Vincent Price that included The Hall of the House of Usher, The Pit and the Pendulum and other classics. In the back half of the decade, he delivered the counterculture touchstones The Wild Angels, which helped usher in a run of biker films that would later include Easy Rider, and The Trip, which, speaking of Easy Rider, was written by Jack Nicholson and starred both Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper.

At the turn of the ’70s, Corman switched his focus to producing, turning his New World Pictures into a kind of hands-on film school for a new generation of filmmakers. Having already helped directors like Francis Ford Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich get started, Corman would now work with names like Jonathan Demme, Martin Scorsese, James Cameron, Joe Dante, John Sayles and more. As the market changed, so did Corman’s focus, but he remains active and keeps an eye on what people want. If you watched movies involving a giant hybrid of sea creatures in the last decade, chances are you saw a Corman production. Most recently, he revisited a ’70s classic via Roger Corman’s Death Race 2050.

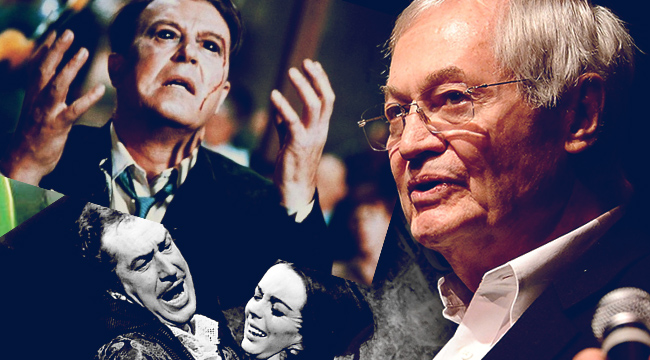

The first annual Overlook Film Festival, an intimate horror movie fest staged at the Timberline Lodge in Oregon, honored Corman with its Master of Horror award, a ceremony accompanied by a screening of one of Corman’s best film’s, the sci-fi horror classic X: The Man With X-Ray Eyes. The evening before the screening, the gentlemanly and self-efficng Corman spoke to Uproxx about his long career.

We’re at a horror festival, so I wanted to start with a big question. Where do you see your enduring contributions to the horror genre?

I don’t think it’s going to be a major contribution. It’ll be a footnote.

I find that hard to believe.

In horror and science fiction, but in films in general, I’ve been at various times a writer, a director, a producer, and even for a little while, a distributor of films. I think of myself as somebody who’s worked in just about every aspect of film. Matter of fact, I was the only producer/truck driver I know. On my first film, I drove the truck.

A representative of the Teamsters came out and said, “Who’s driving the truck on this film?” And I said, “I am.” You know their reputation is that they’re very tough. He laughed. He said, “All right.” I was in my mid-twenties, on my first film. He said, “All right, Roger, we’ll make you an honorary Teamster for this film, but you will be using a Teamster on your next film, won’t you?” I said, “Absolutely.”

That was not It Conquered the World. It was …

Actually, I called it, It Stalked the Ocean Floor, and I sold it to this little distribution company. They thought the title was too arty. They changed it to Monster From the Ocean Floor.

It Conquered the World was shortly after. I was looking at the credits for that. It was your first collaboration with both Charles Griffith and Dick Miller, right? Did you have any idea you’d be working with these guys so much going forward when you made that movie?

Even starting on the first film, It Stalked the Ocean Floor, when the film was over, I made a list of everybody who had worked on the film, and I put them in three columns. One, the guys who did really good, and I absolutely wanted them. The others were the guys who were okay, who did an alright job, and I could hire them or try somebody different, and the other column were the ones that I knew I was not going to work with again.

And I did that over a certain number of films, and certain names kept recurring until essentially, particularly on the crew… My crew became known as the Roger Corman Crew. And they had a certain pride in working together, and normally when a producer hires a crew, he’ll hire a cameraman, he’ll hire a key grip, hire a sound man, and so forth. People would just hire this whole crew, who would be like a football team. You take the whole team. That worked that way with actors, and with writers, and so forth. And they stayed with me, simply because they were good, and we were all friends. We were all young guys getting started.

Horror enters your career pretty early. With Bucket of Blood, I was thinking that’s a movie that could play here, because it’s something that’s trying entirely new things with horror, and working on a limited budget, but doing something really creative.

It has actually played sort of as a retrospective in some festivals, and the audience likes it, because… It was not original with me, but I don’t think it had been done for a while, the idea with combining horror with comedy. I shot it in five days for a very low budget, because I wasn’t certain the combination would work. It was really just, to a large extent, an experiment.

And you followed it shortly thereafter with Little Shop of Horrors, another horror comedy, and certainly one that’s had a tremendous afterlife. It was famously shot in, what was it, two days?

Two days and a night.

Did its long life surprise you?

Yes, because actually I like Bucket of Blood better than Little Shop of Horrors, but Little Shop of Horrors had a spirit, an open, almost naïve spirit to it that caught on a little bit more. Both films did well and they were successful, but Little Shop had this, as I say, sort of naïve, charming quality to it, a little more than Bucket of Blood.

It was not that long after that that you switched from very low budget, very contained things, to your Poe cycle, which has a lot more visual ambition and scope. What made you make that switch?

What happened was this: I was doing a number of films with AIP, and actually for Allied Artists, another low budget company, and they both had a way to distribute films. They would take two 10-day black-and-white films, and send them out together as a double bill, two horror films, two science fiction films, whatever. And AIP wanted me to make two 10 day black and white horror films.

And I was getting a little bit tired of this, and I wanted to move up. And I also felt that they were playing the game a little bit too long, that the novelty of this was starting to wear off, so I said, “Instead of giving me the money for two 10-day black-and-white films, let me make one three-week color film.” And they were a little bit reluctant at first. But I finally convinced them, and I chose Fall of the House of Usher for that. It was partially because I thought from a commercial stand point, the two black and white films was wearing itself out, but more importantly, I just wanted to move on.

It’s definitely not a case of you playing it safe, either. And also as part of the same cycle, you were among the first people to adapt H.P. Lovecraft to film. What brought you to Lovecraft?

What brought me to Lovecraft was I had done most of the major Poe films, and I thought Lovecraft was working in a similar vein to Poe. Personally, I think Poe was a more complex and interesting writer than Lovecraft, but I thought Lovecraft was very good. And I thought, “I can vary this by going with Lovecraft.” AIP, however, just before shooting wanted to make it a Poe film, so I did a little bit of rewriting to make it more like a Poe film. And I think he had written a poem, “The Haunted Palace,” or something like that. So they advertised it as a Poe film, but it was really a Lovecraft film.

Were you surprised these were as successful as they were? This was a case of you really introducing something that hadn’t really been seen in a while in American horror films, the sort of gothic and romantic films. Did you have any idea they would catch on the way they did?

I expected them to do well. I never started out to do a series of Poe films. I simply wanted to make The Fall of the House of Usher, and I expected it would do well. But it became the highest grossing picture AIP had ever had, and they said let’s make another one, and I was happy to do that. And I went, I think I did six of them, and they wanted me to do more, but I said, “That’s it. I’m starting to repeat myself here,” and also this was the early ’60s, and I was shooting all the Poe films in the studio. Because I had a theory, whether right or wrong, that Poe was working with the unconscious mind a little bit before Freud, and I felt the unconscious mind does not really see the world. It gets images from the eyes, and sounds from the ear. It hears, but it is not aware of the world. So I do not want to photograph the real world. I want to be… Everything is artificial. It will be inside the studio. The few times that I’m showing an exterior, I deliberately shot the ocean. And one time I needed a forest, and there was a forest fire in the Hollywood hills, and I shot the-burned out forest. Always making it artificial. Until the last Poe film [The Tomb of Ligeia], I reversed myself and shot a lot of exteriors, just because I got tired of my own theories, but I wanted to move out of the studio.

It was the ’60s. The counterculture was starting, and I did Wild Angels, and The Trip, and simply moved on into a different genre.

Before that there was X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes. How do you feel that fits into your filmography ? Because it is a return to science fiction, which you hadn’t done for a while, but also very much a horror film.

I think it fits in as a progression. Not every film is a straight upward progression, but I think X: The Man with X-Ray Eyes is an interesting film, because it had many of the elements of the Poe films, but a number of elements that were new. I generally write a five or ten page outline of the script, and then give that to the writer. I’m no writer, and I knew I wanted to do a picture about somebody who was able to see through things, and see through things increasingly. And my first idea would be a scientist such as Ray Milland in X-Ray Eyes, but I thought, “That’s too obvious a way to go.” So I decided to do it about a jazz musician who had taken too much drugs, and I get into about four or five pages, and I thought, “You know, I don’t like this idea,” and so I threw the whole thing out, and started back and went back with the scientist, which was the original idea.

Now it’s interesting, Stephen King saw the picture and wrote a different ending, and I thought, “His ending is better than mine.” And of all the pictures I’ve made, I think… Matter of fact, I’m thinking possibly of doing this, of remaking it, because the effects of seeing through things were only what I could do with a limited budget. And it was around 1960, ’59 or ’60, something like that, with the type of special effects we had. And of all the films I’ve made, the new special effects with computer graphics and so forth, I could do a much better job today than on that one.

I think though sometimes the limitations of effects kind of lend a dreamlike quality that more advanced special effects I don’t know if you ever find that as well.

It could be. I never thought of it in those terms. Part of the limitation was, a lot of times I deliberately would have the camera fractionally out of focus, not heavily, but just enough to give it a weird look. And I used smoke a lot also, all the things you could do in those days, and some optical printing, which I would reprint with different colors over the same negative But those were … They don’t compare in any way to what can be done now.

Do the new special effects excite you?

Yeah. I like the idea, because it’s fun. You can really spread yourself, and you’re not tied to a specific plot point or narrative line. In a lot of [my movies], there were fantasy sequences. There would be a theme to the sequence, but it could be anything that I wanted. So I’d start with one idea, and as I’m doing all this, I or the editor, or… There were a couple of people that specialized in that type of special effects. We were all working together on these. And one of us would get a different idea, so each one of those sequences grew and changed as we played around with it. That was just fun to do.

For something like The Trip, I love what you did with the effects technology you had at that point.

Well, we brought in some lenses. I heard about this, and Archie Dalzell was the cameraman. It was the first picture he had done with me. He was an older guy, and I talked to him, and I said, “I’ve heard of all kinds of lenses that people are using now,” and he said, “Yes.” So he went to… I’ve forgotten the name of the company. But it was a camera rental place, and he found all of these old lenses. And we would put all these different lenses on the camera, and then move sometimes the lens itself, so the whole thing became distorted. So we were just trying anything we thought we could do, including the extremely fast editing on those sequences.

There’s a lot of ambiguity to the attitudes of movies like The Trip and The Wild Angels. They had this rebellious spirit, and the heroes — either the bikers, or in The Trip the drug users — are rebelling against the establishment. But there’s sort of a sense that this might have gone too far.

Well, I think it was hard. It was the early days of the counterculture films, and these were among the first ones. I don’t know if they were the first. But The Wild Angels… This film was the biggest-grossing low-budget picture in history. That record was broken just a few years later by my graduates on Easy Rider, who broke that record. I was supposed to be the executive producer on that, but then AIP made some mistakes, and they infuriated Peter [Fonder] and Dennis [Hopper], and so the film moved on.

But The Wild Angels was the opening night film of the Venice Film Festival. And it was very well received, and I was supposed to leave afterwards and go to Morocco to scout a location for a picture. And the day after the screening, the head of the festival said, “You should stay around. You’ve got a chance to win this festival.” And so I went up to the screening the next night, and the next night The Battle of Algiers showed. And the next morning I said to the head of the festival, “I know when I’ve been beaten. I’m leaving.” The Battle of Algiers did indeed win. Great picture.

There must be stories about the making of that film using real Hell’s Angels.

Well, there are stories about them. Chuck Griffith, another writer, and I went to a number of their parties. We brought the marijuana, so we were always welcome.

Everything was based on what they told us they had done. It wasn’t until after I made the film the thought occurred to me, “How do I know that this stuff really happened?” I mean, people exaggerate a little bit. And one of the things I remember, I had to pay them by the day. I paid a certain amount to the Angels. I paid a certain amount of money for his bike, and then I paid a certain amount for his old lady. They wanted more money for the bikes than the old ladies. But after the picture was over, and the picture was such a big success, they sued me for defamation of character. And I remember I was watching it on a news program. It was a local thing, and the announcer started… He stifled a laugh. You could see him starting to laugh. He said, “Hell’s Angels are suing Roger Corman on the basis that he portrayed them as an outlaw motorcycle gang, when in reality they are a social group dedicated to spreading technical information about motorcycles.”

So I got a call from big Otto Friedli, the leader of the Angels, a little bit after that. He said, “Hey man, we’re gonna snuff you out,” and I said, “Well, Otto, think about this. You have now publicly said that you’re gonna kill me. If I slip and fall in the bathtub, the police are gonna come after you. Also, you’re suing me for a million dollars. How do you expect to get the million dollars from me if you kill me? My advice to you is, forget the momentary pleasure of snuffing me out, and go for the million dollars.” He thought about it and said, “Yeah man, we’re gonna go for the million dollars.”

In the early 1970s you segued out of directing for a long time.

What happened was this. I was shooting Von Richthofen and Brown, a World War I flying picture in Ireland. Not a great place to shoot a flying picture, but there were some World War I airplanes there that had been used in a big budget film. And I didn’t have that much money, so I went where the airplanes were, where I could rent them, and I was just tired. I had directed so many… I directed around 60 films in 12 or 13 years, something like that.

It was just too much. Every morning … I had a little apartment in Dublin. We were working at this private airport outside of Dublin, and every morning I would drive from my apartment to the airport, and I remember there was this split in the road. It was this way to the airport, and this way to Galway Bay, and every morning I was tempted to say, “I’m just gonna go drive the Galway Bay.” I’d never been there, ” … and just sit on the beach,” and I thought, “I’m gonna stop for a year.” I never planned to stop directing. I just felt, I’m gonna take a sabbatical, a year off.

But I got bored during the year, and I got back. Stephanie Rothman had been making a little picture called The Student Nurses, and decided to form a company [New World Pictures] and distribute it myself, and the thing was a big success. Suddenly, all the films were successful, and I found myself just producing, and I just didn’t get back to directing.

As much as has been said about the talent that came out of that, is there a film from that era that you feel that people should pay more attention to?

Well, there are a number of them that I thought were very good. There was a science fiction film, Battle Beyond the Stars. The first Piranha film was good, but there are others that were more important… Rock ‘n’ Roll High School. I always liked that picture. I always loved Rock ‘n’ Roll High School.

There are a number of others. Oh, we had a number of women in prison pictures shot in the Philippines. Now, weirdly enough, the first one was rougher than I thought, and I was… Jack Hill made [The Big Doll House], and Jack and I went over it, and I persuaded him to trim just a little bit, but he said, “It needs all of this.” And I said, “Well, if you really think that, Jack, okay.” But frankly, I didn’t particularly like the film. I thought we’d gone too far.

The film was a sensation. And so we immediately followed it up with The Big Bird Cage after The Big Doll House. There’s nothing particularly to be said about those films, except they were so successful, and they combined women as the leads. And one of the troubles I had with writers on that — and The Student Nurses led to Private Duty Nurses, and so forth — was the idea of women as leads. Several times I would tell a writer of the idea, and they would write another line, and the girls’ boyfriends would come in and solve the problem. But I had to say, “No, the girls solve their own problems. That is the key to this.” And I think we hit something a little early, because some woman from a feminist magazine called me and said she’d been hired to write about this, and she was going to attack them, and after she saw them she said despite their exploitation that she considered them to be feminist films. So maybe there was more in those films than I thought.

When I watched the documentary about you a couple of years ago, Corman’s World, I was surprised and very impressed by how hands-on you still are with the films you make. It would probably be easy to kind of lay back and not do as much, but is that just not in your nature?

It takes the fun out of it, if you’re just sitting in your office. There was a couple of car racing films, not recently, but a few years ago. I was one of the stunt drivers. I was one of the stunt drivers for a simple reason. Stunt drivers get a salary, but if they do a dangerous stunt, they get what’s called a bump. Which is a bonus, and for a really dangerous one, they get another bump. Well, this was the original Death Race 2000. Stunt drivers wanted a double bump on this, and I said, “Forget that.” Paul Bartel was directing the film. I said, “Forget that. Give me the helmet.” So I did the stunt, and to me that was fun. These guys said this was dangerous? Didn’t seem like it was dangerous to me. It seemed like just fun driving wildly.

You directed one more movie, Frankenstein Unbound in 1990. Do you ever regret not being behind the camera as a director?

Sometimes. In the early years after I started New World, I was always thinking, “Well, I will direct again.” And I thought, “There are two ways I would direct again, and I could go either way. It should be something I really believe in and I want to make, or it should just be the next picture on the line, and I just go out and direct it.”

I don’t know, I just… The work was so huge. We were making so many films. We were making 10, 11, 12 films a year, because we were our own distributors. It was my own distribution company, and we used to say, “We have to feed the dinosaur.” The dinosaur is the distribution company, and we had to make enough films, so the distribution company would have enough films to distribute and make some money, and the work was just so much. I just never got around to it.

Is there a place for the types of movies that you’ve always made in this sort of streaming future that we’re going into right now?

There is, but it’s more difficult. Somebody asked me on another interview somewhere about the changes. And I said, “There are two major changes. The making of the film is easier. We had the big cameras, and all the huge lighting equipment and so forth. The brutes, these giant lights it took three guys to move, and with the lightweight digital equipment, you can move faster and more efficiently, and make a film more easily than we made films, but the distribution is tighter. When I started every film that had at least some commercial merit, it got a full theatrical release. I never made a film that didn’t get a full theatrical release.

But today, very few medium- or low-budget films get a theatrical release. Every now and then… [Blumhouse] producer Jason Blum, he’s one of the few who’s been able to carve a kind of niche there with slightly more expensive films, and get a theatrical release. But by and large, theatrical films today are the province of the major studios and the big-budget films.

I can’t help but feel that something’s lost when that’s the case though.

Yes, because there is a certain sameness. That’s why I refer to Jason, and the fact that there still is a little market. I think that market may grow. I don’t think it will grow wildly, but I think it may grow a little bit as we’re beginning to see, or as we have, and as we easily predicted. I predicted it. Many people predicted it. There can be a couple of these $200 million pictures that are gonna fail, and you fail with a $5 million film, that’s something. You fail with a $200 million film, and heads are gonna roll. And I think the market is possibly becoming saturated, and we’ve seen a number of those fail, and I think the audience is ripe for a different kind of experience. And I don’t think independent films will ever come back to where they were in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s — but they may come back a little bit.