The band is composed of two French guys from Versailles who met when they were 15. As kids, they played rock and roll, but when their label insisted that they sing in French instead of English, they stopped. Singing rock songs in French just seemed wrong to them; besides, they knew deep down that they’d never be the Stooges. They were just too … French. So one guy decided to study architecture, and the other guy taught mathematics and physics at a university. Around them in Paris, however, there was a burgeoning electronic music scene just beginning to flourish, and it pointed a new way forward.

“Playing guitars loud through amps is great fun when you’re 15 and full of hormones, but French people are better at being chefs or fashion designers,” Nicolas Godin remarked decades later. “Rock music is not really in our culture. But electronic music is different. When we discovered it, suddenly we had an outlet.”

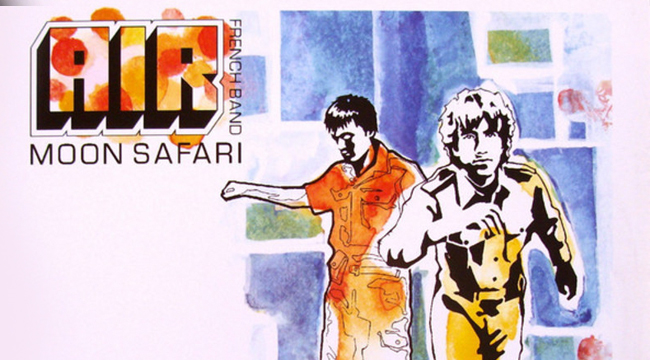

Godin and his musical partner, Jean Benoit-Dunckel, went on to form Air, and eventually released one of my favorite albums ever, the landmark Moon Safari, 20 years ago this month. At the time, Moon Safari stood in marked contrast to the other major crossover French electronic LP of the era, Daft Punk’s Homework, which dominated MTV and hip mixtapes everywhere with nu-disco bangers such as “Around The World” and “Da Funk.” While Daft Punk catered to Saturday night ragers, Air’s contemplative interstellar muzak was strictly for the Sunday morning brooders — or, perhaps, for those who didn’t go out on Saturday nights at all.

As Dunckel later admitted, the Air pair “didn’t get to go to all the parties” that were happening around them during the gestation of Moon Safari. Instead, they obsessed over writing pocket symphonies that melded Burt Bacharach, Serge Gainsbourg, Pink Floyd, and Herbie Hancock’s Thrust on what became (to quote fellow travelers in ’90s chill-out jams Stereolab) the ultimate in space-age bachelor pad music. “We were poor,” Dunckel explained to The Guardian in 2016. “I knew our livelihood depended on Air being successful.”

Honestly, I didn’t know any of this stuff until just a few days ago, when I decided to finally figure out why Moon Safari has resonated with me for so long. Even as a person who is professionally obligated to intellectualize everything he listens to, I’ve never felt compelled to dig past the music of Moon Safari. I knew virtually nothing about Godin or Dunckel, or how they hooked up with Beth Hirsch, an American singer-songwriter who sings and co-wrote the album’s two torchiest ballads, “All I Need” and “You Make It Easy.” (Apparently, she was Godin’s neighbor.) I didn’t bother to look up the meaning of “La Femme d’argent” (“The Silver Lady”) or “Ce matin-la” (“The Morning”), even with my rudimentary background in high-school francais. I didn’t even read the liner notes. I still listen to Moon Safari a couple of times per month — it’s my go-to writing album, along with Air’s 2004 masterpiece Talkie Walkie — but for the longest time I remained willfully ignorant of even the album’s most basic facts.

I think I liked the idea that Moon Safari only existed inside of the contours of my own head. The lightly strummed acoustic guitars, the gently bobbing congas, those perfect synth tones — Moon Safari has hummed as a warm and calming antidote to the feverish anxiousness of my interior monologue for years now, to the point where the music seems almost impossible to analyze. How do you articulate your feelings about something that has come to be an abstract part of your own inarticulate consciousness?

What’s weird about Moon Safari is that it seemed to have already resided deep inside my limbic system even as I heard it for the first time. I imagine this was true for others, as the record was frequently described as nostalgic. “They build their music out of classic ’60s French schlock: bongos, castanets, vintage electric piano, dream-weaver synths and shag-carpet organ straight from the soundtracks of movies like Un Homme Et Une Femme,” Rob Sheffield sharply observed in Rolling Stone. For a generation of Gen-Xers, Moon Safari evoked childhood memories of soft-focus, soft-rock comfort. (Godin himself likened Moon Safari to The Carpenters.)

But for me, Moon Safari wasn’t reminiscent of music I heard when I was 5 and wiling away days on my back on the living room floor, surrounded by Legos and Star Wars action figures. If that were the case, Air would’ve sounded like REO Speedwagon’s Hi Infidelity. Rather, Air evoked the feeling of remembering my past and noting all of the things that I’ll never experience again. Moreover, it made me feel melancholy for things that I hadn’t actually experienced, but felt like I had — which is common among young people who haven’t accrued enough loss to feel mournful, and yet like the romantic idea of loss nonetheless.

Moon Safari came out when I was 20, an age when you’re still not that far removed from your childhood, but feel compelled to separate yourself from your adolescent self out of embarrassment and pre-emptive nostalgia. You want to be seen as an adult, but you also want to self-mythologize your own origin story. While some were content to contextualize Moon Safari as semi-ironic camp — Sheffield called it “a sublime Eurocheese omelet” — Air’s music to me doubly ached, as a skeleton key for accessing my own evaporated history as well as a universal, imaginary past that felt instantly familiar and yet indelibly alien.

If Moon Safari struck a chord with listeners as both a personal memento and a lush fantasy, it performed a similar function for Godin and Dunckel, who found a sweet spot between fetishizing vintage gear (the pair credit Lenny Kravitz’s breakthrough album Let Love Rule with bringing that into vogue) and the embrace of samplers introduced by hip-hop acts in the late ’80s and early ’90s. As a result, Moon Safari can be a difficult record to classify. It’s often called electronic, but so much of it is acoustic and resolutely analog, actively resisting the digital chill. It has that Floydian spaciness — Dark Side Of The Moon was a huge hit in France — but its normcore facade is the antithesis of psychedelia. It is superficially retro, but also futurist — at least it was in 1998 anyway.

The Air sound evolved out of the expansive, pan-cultural vibe of so much late-’90s music, a time of rap-rock and arena-rock-style country and funky Odelay-inspired indie. But the record is also insular and idiosyncratic, the work of two shy and quiet sci-fi fans who felt like they were stuck on another planet inside their own country, which was slow to embrace Air amid a field of more extroverted and boisterous electronic acts, even as Moon Safari took off in the UK and US. Embedded in the velvety, Kubrickian grooves of Moon Safari is a discernible sense of yearning to reconnect with what’s you’ve lost, or to finally capture a bygone innocence you never truly experienced in the first place.

“What I like and what I’m capable of are such different things,” Godin said in The Guardian. “I like the Stooges, but I would never play music like that because, in my culture, I would look ridiculous. When I got older, I discovered a type of music that fit my personality and my culture, and that became the Air sound. It’s really funny: I just needed to give up the teenage years.”

The contradictory impulse of Moon Safari — be yourself, and also be the self you’ve long imagined yourself to be — is central to the album’s biggest hit, the seductive homoerotic goof “Sexy Boy.” With its leering bass line, metronomic beat, and robo-girl vocals, “Sexy Boy” plays like a pisstake on oversexed machismo that also doesn’t shy away from the very real pleasures that occur in the dark of a seedy disco. The song was, in other words, utterly unlike day-to-day reality for the club-averse Godin and Dunckel, and yet it distilled their post-modern sensibility perfectly.

“One day I played a riff to JB and he said ‘sexy boy’ out of the blue — and that was how we got the song,” Godin recalled. “If we’d sung ‘sexy girl,’ it would have been a disaster. ‘Sexy Boy’ felt different. The song was about who we wanted to be; we weren’t handsome when we were younger; our friends always had more success with girls.”

The success of “Sexy Boy” and another single, “Kelly Watch The Stars” (inspired by Jaclyn Smith’s character on Charlie’s Angels), made Moon Safari an international hit, even though Godin and Dunckel never exactly embraced rock stardom. In Mike Mills’ snail-paced 1999 tour documentary Air: Eating, Sleeping, Waiting, And Playing, we see the Air boys killing time between gigs by listening to classical music and reading sheet music (!) in their hotel room.

“We didn’t move to London at the time, or LA,” Godin told the website Loud And Quiet in 2016. “ We kept our originality. Otherwise we would have been part of a professional world and we never wanted to do that really. We wanted to be more like normal guys who do some crazy stuff in the studio with free spirit, you know?”

In the studio, Godin and Dunckel could be sexy boys who took day trips among the stars. How could conventional music stardom compete with that? Like those of us who love Moon Safari, they wanted to believe the album only existed inside of their heads, too.