This essay is running as part of the 2019 Uproxx Music Critics Poll. Explore the results here.

There’s something about the end of a decade that makes people freak out. Turning over the calendar can represent the promise of new beginnings and exciting, unforeseen possibilities. But more often it just seems to create profound anxiety about how we’re all doomed. In each and every decade, right about now, it not only feels like the conclusion of an era, but also like the end of the world.

Looking at the past 50 years of popular music, a familiar pattern of end-of-the-decade dread emerges. A half-century ago this month, The Rolling Stones released one of their greatest albums, Let It Bleed, and bookended it with two rock classics about the apocalypse: “Gimme Shelter,” which declares that widespread annihilation is “just a shot away,” and “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” an epitaph for the faded flower-power “peace is possible!” delusions of the sixties. Critics immediately gravitated to these themes and how they spoke to a time of war, assassinations, and intense political polarization. Greil Marcus memorably called Let It Bleed an album about “this era and the collapse of its bright and flimsy liberation” in his review for Rolling Stone.

Almost exactly 10 years later, The Clash put out London Calling in December of 1979. The album opens with the rousing title track, in which Joe Strummer paints a dire portrait of contemporary England under siege from foreign invaders, morally and artistically bankrupt culture, and climate change. (Though Joe was obsessed with the ice age, not global warming.) Rolling Stone later called it the best of the album of the eighties, perhaps the most egregious example of music publications bending the calendar to the will of their list-making deadlines.

A decade after that, the most critically acclaimed song of 1989 was Public Enemy’s “Fight The Power,” arguably the greatest protest anthem ever, in which Chuck D declared rhetorical battle against white supremacy in terms that were meant to inspire an actual revolution. Rage Against The Machine struck a similar do-or-die posture in 1999 on one of the year’s most popular and critically praised rock records, The Battle Of Los Angeles, while The Flaming Lips ruminated over mortality and how a lost and unjust world was “waitin’ for a Superman” on the year’s most beloved indie LP, The Soft Bulletin.

By 2009, this fretting over the inevitability of death — our very own personal apocalypse — was leavened by the optimism of the early Obama era. You can hear that hope in the domestic fantasies of that year’s best reviewed album, Animal Collective’s Merriwether Post Pavilion, in which Noah “Panda Bear” Lennox sings about how he only wants “a proper house,” a relatable desire as the US housing bubble burst and a lingering recession descended and never seemed to fully leave in the 2010s.

All of this, of course, is a preamble to right now. What’s immediately apparent from Uproxx’s annual critics poll is that the best-regarded albums of 2019 were often preoccupied with seemingly unavoidable worldwide destruction. After all these years, our fiery denouement still feels like it’s just a shot away.

The cataclysmic challenges posed by climate change is a central theme of Weyes Blood’s lovely soft-rock fantasia Titanic Rising, in which Natalie Mering mourns for a world that she’s already given up as a lost cause. “It’s a wild time to be alive,” she sighs sardonically, a tone that also recalls the weary resignation affected by Ezra Koenig in “How Long?” from Vampire Weekend’s loveably shaggy Father Of The Bride. “How long ’til we sink to the bottom of the sea?” he wonders.

Jenny Lewis is less direct about her apocalyptic angst on the excellent On The Line, though the imagery she uses throughout is similarly funereal. (“After all is said and done / We’ll all be skulls,” she concludes in “Heads Gonna Roll.”) Even Taylor Swift, who was roasted on social media for being publicly apolitical during the 2016 presidential election, plugged into our collective malaise on her “comeback” album, Lover, admitting “honey, I’m scared” in the sorta-political song “Miss Americana And The Heartbreak Prince.”

And then there’s the year’s most critically adored LP, Lana Del Rey’s Norman F*cking Rockwell, an album I found fascinating, funny, mesmerizing, and frustrating in equal doses. The most powerful track from NFR, “The Greatest,” is an almost too-gorgeous song that is structured like a final missive from a dying planet. The closing lines are especially well-drawn and cinematic:

LA is in flames, it’s getting hot

Kanye West is blond and gone

“Life on Mars” ain’t just a song

Oh, the live stream’s almost on

What kept me from fully embracing Del Rey’s unquestionably impressive and thoughtful magnum opus is the glib nihilism of the album’s most quoted lyric: “The culture is lit and I had a ball.” You see this sort of sentiment pop time and again in social media, that numb semi-jokey passivity about how this is a hell world and life is a garbage fire and how everything is getting worse and there’s nothing we can do to make it better. I certainly understand why people feel that way, and how writing a quippy tweet that garners hundreds of likes and retweets might offer temporary respite from the nonstop cavalcade of anxiety-inducing oncoming disasters we’re faced with everyday. But I also can’t really buy in. I won’t buy in, because truly believing that the world is about to end would make me want to quit this life right now.

It would, in other words, make me feel like David Berman, whose Purple Mountains album devastated more than any music I heard this year, and whose suicide one month after the album’s release this summer continues to disturb me tremendously. Berman’s wordy folk-rock dirges aren’t for everybody, but the one thing his detractors can’t accuse him of is being glib. Here was a man, in the astounding “Margaritas At The Mall,” who angrily denounced the ambivalence of God in a world with so much suffering, and then followed through on his despair with a horrible, tragic act of self-erasure.

Berman’s shocking death signals the key difference about the apocalyptic music of 2019, in comparison with end-times pop from the past like “Gimme Shelter” and “London Calling” and “Fight The Power” and even “Waitin’ For A Superman” and “My Girls.” So much of our music this year lacked any defiance in the face of what seeks to destroy us. We didn’t gravitate to noisy and brash protest songs in which we were implored to take action. We instead filled our heads with pretty, mellow, slyly witty, and thoroughly defeated gallows humor predicated on the assumption that our fates are already sealed.

And while I enjoyed a lot of that music aesthetically, I reject it philosophically. I love David Berman’s music, but I don’t want to end up like him. Instead of “the culture was lit and I had a ball,” I found more resonance in “I don’t wanna live like this, but I don’t wanna die,” from Father Of The Bride‘s central track, “Harmony Hall,” a lyric that acknowledges the gravity of our situation without surrendering to it.

Like Ezra Koenig, Sharon Van Etten recently became a parent. Her stunning LP Remind Me Tomorrow is infused with the (perhaps misguided but still undying) hope for the future that you must have when you bring a new person into the world. The album concludes with “Stay,” a deeply moving hymn sung by a mother to her child:

Find a way to stand

And a time to walk away

Letting go to let you lead

I don’t know how it ends

This is a song about wanting to be there for your child, even if you can’t guarantee what kind of future that child will have, as an act of faith. Maybe this is a hell world. And if you’re convinced that the clock is running out on us, I can’t conjure a persuasive argument to the contrary. But for now the world is still turning, and while the minutia of our petty jealousies and facile obsessions ultimately pales in comparison to the calamities that await us all, I’m still thrilled to be alive.

Which is why, in spite of everything, I was delighted by Angel Olsen’s All Mirrors and Tyler The Creator’s Igor, both of which treat romantic hardships like the end of the world. Because that’s how they feel when you’re in the middle of them. Having your heart stomped on is the best-worst part, and the worst-best part, of being on this planet.

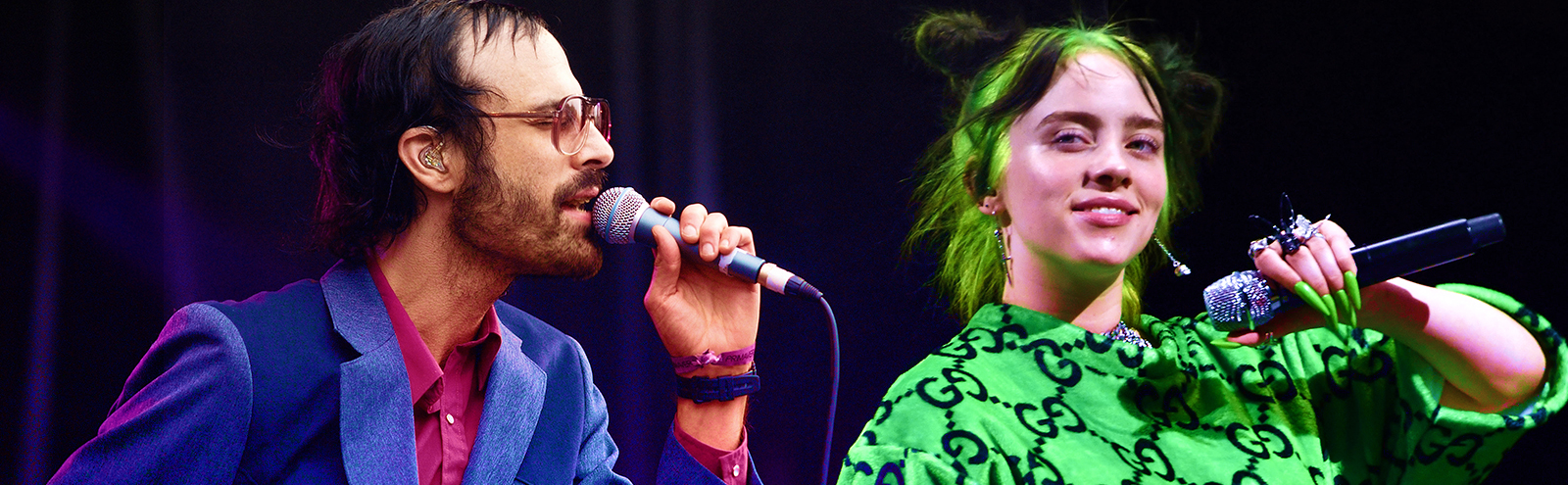

And who could ever forget the great Billie Eilish, who turned 18 this week and acts like it in all of the ways you would hope. That “NO MUSIC ON A DEAD PLANET” T-shirt she wore on the American Music Awards showed her political awareness, but her defining statement of 2019 was that perfectly snotty “duh” that sends her massive hit “Bad Guy” into the stratosphere. Even as we stare down our possible extinction, the insouciance of our most famous teenager remains undiluted. Bless the indomitable human spirit.