Breaking Bad turns 10 years old on Saturday. It doesn’t feel that way, perhaps because so many people discovered the series years after it debuted, perhaps because Better Call Saul is keeping this fictional universe alive, or perhaps because Breaking Bad was just that great — and just that influential to what TV drama looks like now.

Breaking Bad turns 10 years old on Saturday. It doesn’t feel that way, perhaps because so many people discovered the series years after it debuted, perhaps because Better Call Saul is keeping this fictional universe alive, or perhaps because Breaking Bad was just that great — and just that influential to what TV drama looks like now.

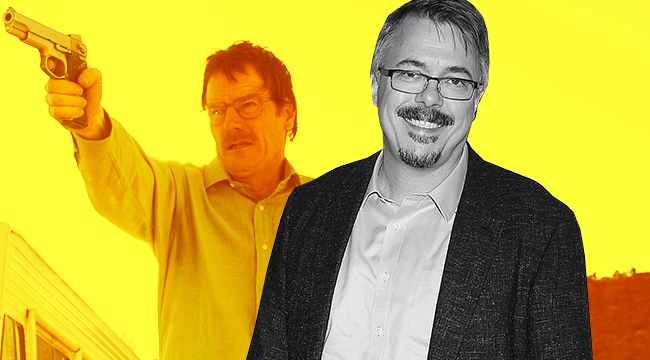

I’ve written a lot about the show over the last decade — including a book, Breaking Bad 101: The Complete Critical Companion — and one of the recurring themes of both the story of Walter White and the writing of that story is improvisation. Walt and his creator, Vince Gilligan, don’t have much in common — Gilligan is generous and self-effacing almost to a fault, where Walt was arrogant and entitled to the core — but they do share a knack for stumbling into dangerous situations and only figuring out how to escape once trapped there.

Many of the most iconic Breaking Bad story moments were reverse-engineered, with Gilligan or another writer coming up with a memorable image and everyone having to work backward to get Walt and Jesse there. Others were plotted out the usual way, but involved Gilligan and his team burying their faces in their hands trying to figure out how Walt would get out of the latest fix they’d impulsively crafted for him.

To celebrate the show’s tenth anniversary, I asked Gilligan to talk about some of the tightest corners he and Walt painted themselves into, and how difficult it was to find the exit.

What to your mind was the toughest one you ever had in terms of, “What on earth are we gonna do now and why did we do this to ourselves?”

Well, my knee-jerk, Rorschach test reaction to that question is definitely the M60 machine gun.

That’s the one that pops into my mind. There were, to be sure, a great many and we could talk all day about it. All the time, we idiotically painted ourselves into a corner in the writers’ room. But the worst of all, in my memory, was the M60 machine gun. At the beginning of the final 16-episode run of the series, we’re there in the writers’ room and I’m thinking, “We gotta open this thing with something interesting and evocative. Something that tells us, oh man, there’s big drama afoot in these final 16 episodes.”

I don’t even remember who got the idea, because again, as I’ve said many times in interviews, the beauty of a writers’ room is it’s just one big hive mind. It doesn’t matter who says what. But the idea got floated that Walt buys this big belt-fed machine gun in the parking lot of a Denny’s. We had no frigging idea of what we were gonna do with that machine gun when we conceived of that.

And I figured, “Wow, 16 episodes. Oh man, we got all the time in the world. We’ll figure it out.” No idea what the hell Walt needed this thing for, which was so idiotic in hindsight. And I gotta tell you, the reason I remember it very distinctly is because working on the final four or five episodes of Breaking Bad, and my writers very astutely reminded me over and over again, whether I wanted to hear it or not, that we needed to work this machine gun thread into the storytelling.

At a certain point, I so did not want to hear it, and furthermore, I would have these flights of fancy where I would say, “You know what? Let’s pretend the machine gun thing never happened.” And they would say, “Okay. We can do that, but what’s the point?” I said, “What would we do without the machine gun?” And they would, again rightly say, “Well, it doesn’t really matter what would do, story-wise, without that because we gotta pay that thing off.”

Then I would get mad and sometimes I would pound my forehead against the wall, literally, because I don’t know why, that helped. Or at least I felt like it did.

Was there a eureka moment with that one?

I mean, I guess there was. You know what? The thing of it is in the writers’ room, it’s just such a slog and I’ll bet you every TV show works the same way. If you’re writing a scene that took place in a writers’ room, you would have a eureka moment where somebody says, “I got it!” And you have big drama and everybody then dances and breaks open the champagne.

The trouble is in reality, there seldom are any big eureka moments because it’s just like moving across no man’s land in World War I. It’s like trench warfare. You’re lucky if you can move six and a half feet in a month. You barely get anywhere. It’s just an inch at a time. You’re just crawling on your belly though the mud trying to, figuratively speaking, trying to figure all this stuff out.

So, I don’t remember the big eureka moment. I remember, obviously we talked about, well, what do you need a machine gun for? It’s not just for killing one guy, it’s for a whole squad of guys. So, slowly but surely we started to figure out, “Well there’s gotta be a gang in there somewhere,” and the white supremacist gang led by Uncle Jack came into being. As always, we tried to play chess 20 moves ahead, but that’s as hard as it sounds. It’s really hard to figure that stuff out. So I don’t remember any particular eureka moment.

After that, what corner was most painful to get out of?

Another one that pops into my head is Walt and Jesse stuck in the RV in the junkyard with Hank circling the RV like a shark and knowing that Jesse was inside, but not knowing that Walt was inside. That was a big one. And when you think about it, that’s the genius of Walter White: he figures out answers to problems that in real life, it took eight fairly smart people probably a week and a half to two weeks to figure out.

In other words, we get him to that point and Hank is outside and Hank is relentless, as we know him to be. How in the world is Walt gonna get out of this? And every conceivable thought under the sun comes up, no matter how stupid. We’re talking at one point about, well, they cut a hole in the bottom of the RV and then the dig a tunnel. Asinine.

And then the very obvious but horrible thoughts pop into your head too, like well, “What if Walt opens the door and Hank looks at Walt and Hank is dumbfounded and there’s this huge moment, this huge pregnant pause and then, in that moment of dumbfoundedness on Hank’s part, Walt shoots him in the head and kills him?” It’s just every idea under the sun comes into play.

What are some others?

Well, it’s not as much of a cliffhanger, but one of the most important twists we ever came up with was for episode four of the very first season. It suddenly dawned on us that we needed to change up Walt’s behavior a bit. In the early days, we figured the show was gonna be, Walt’s gotta make money for his family. So, how mechanical a process is that gonna be? Is he gonna make a thousand bucks and then he loses it? He gets mugged or crows fly off with it, build a nest. Or he makes ten thousand bucks this week but then he loses it? It threatened in the first few episodes to become very mechanical, the storytelling. And a twist that we came up with of Walt really enjoying this criminal behavior and wanting to do it regardless of the money.

In other words, Walt doing it for himself rather than his family was a very important twist that came four episodes in and prior to that, we didn’t see that coming. That Walt really was not doing it for his family, that’s the ultimate twist. But I don’t know if that helps you for this, because that’s not really a painting oneself into a corner type thing.

One that several other Breaking Bad writers have brought up to me is how Walt was going beat Gus and even get close to Gus, because Gus was so powerful and so far removed. How long did that take?

Oh man, that took forever! The trouble is, when you’re telling stories, when you’re writing a story about formidable foes, you want them to be as smart as possible. And Gustavo Fring almost took on a life of his own. He was almost supernaturally smart and we figured, who better? The smartest guy on this show up til now has been Walter White, and we love the fact that we had inadvertently come up with a character who’s even smarter than Walt.

So then we figured then we really were stuck because it’s like the Old West town. This town’s not big enough for the two of us. Or if you like the Highlander metaphor better, there could be only one at the end of the day, between Walt and Gus, so we had to have Walt prevail.

The temptation when you’re really desperate and the clock is ticking is to have your genius bad guy character do something stupid. But you feel really terrible at heart when you’re pitching those kind of ideas because you say to yourself, any dumb mistake that the bad guy makes lessens the good guy’s brilliance and the good guy’s fortitude and all that kind of stuff.

So, we made a promise to ourselves: “We gotta keep this guy smart all the way to the end.” And yet, if he’s so brilliant, how does he fumble? And it took forever as I recall, but it really became a combination of Walt being brilliant and desperate and Gus having a previously unknown to the viewer Achilles’ heel, which was an emotional attachment to a need for revenge against Hector Salamanca.

So we came to create this whole backstory about how much Gus Fring hated Hector. And we created that long after the first episode, during which we saw Hector and Gus together. It came later, that backstory of this loathing Gus Fring had for Hector Salamanca, as a device, as a way in to allowing Gus to make a mistake, and let Walt get too close to him.

In a weird way, a lot of the most emotional character-driven beats throughout the life of Breaking Bad were created for very meat and potatoes logistical reasons, which I find kind of funny in hindsight.

I’ve heard that coming up with the details of how the plane crash happened was an enormous headache. You knew going into the season that there was a crash, and you started putting in those clues, but actually figuring out how it would happen was a problem.

That’s a good example. This just shows how ass-backward we work quite often in the writers’ room. The best kind of storytelling, I believe, is organic storytelling, where you start with a character, an understanding of your character, and then the character’s needs, and then you go from there. Your left plot derives solely from character and the needs and desires of characters.

Having said that, we were as inorganic as hell a lot of the time. And I almost feel guilty that we got rewarded for it. But I remember at the beginning of season two, we just had this image in our heads of this burned wreckage around Walt’s pool and a teddy bear with a scalded face, burned-out face floating in the pool. And, in the earliest days, we had no idea at all what that image meant. We just know we wanted to run with it.

So, we thought to ourselves, “Well maybe at some point, by the end of this season, Walt for some reason had a meth lab in his house and then it blew up.” And then we thought, ” What in the hell, he would never do that. Why would he do that?”

And then we thought, “Well maybe the house got blown up, or maybe there was a home invasion, some terrible thing.” Finally, we came to the idea of the airplane crash, because if for no other reason, we felt like, “Well, this is one nobody will see coming.”

But then, if you’re not being lazy with your storytelling, then it quickly dawns on you, “Well, it can’t just be a plane crash out of the blue. That’s not Drama 101. It needs to be something that the main character action’s put into motion.” So you can’t just have a plane crash unless Walter White somehow is responsible for it, at least inadvertently.

Once we knew it was a plane crash, then we quickly knew, well, “Walt has to be responsible somehow, in some measure.” And then, the rest of the season was this agonizing slog of, “How in the hell can Walt possibly be responsible for this?”

It took many weeks and months, in little baby steps, little dribs and drabs, that led to the creation of a girlfriend for Jesse, which led to the character Jane. And then Jane’s father, the air traffic controller who, we purposefully left out, for the audience, we left out what he did for a living until much later. Long after we’d met the fellow.

The thread that links all these stories together is when we did stupid, somewhat self-destructive things like, come up with images and then lazily say to ourselves, “Well, we’ll figure out how this all pays off later.”

The thing I’m proud of… That was dumb. I’m not proud of that. But I am proud of the fact that later on, despite all the blood, sweat, and tears, we didn’t give up or give in in terms of explaining these and paying off these plot twists until we knew we had a sufficiently appropriate and dramatically interesting reason or explanation for them.

Alan Sepinwall may be reached at sepinwall@uproxx.com. He discusses television weekly on the TV Avalanche podcast. His new book, Breaking Bad 101, is on sale now.