On Castle Rock, Tim Robbins plays Reginald “Pop” Merrill, a dying man with stains on his conscience, worry on his mind, and Lizzy Caplan’s Annie Wilkes freshly stuck in his town. For Robbins, it’s a return to the world of Stephen King, the man who created the character for which Robbins may best be known, Andy Dufresne from Shawshank Redemption. But for the actor, filmmaker, and activist, the King connection is little more than trivia. With Pop, the there there is the challenge of playing something Robbins never has before. Which is saying something considering the myriad roles he has occupied in his lengthy and impactful career.

Along the way, Robbins has gained some insight and seems to have long ago discovered the value of speaking his mind, holding onto creative freedom, and blending the two into pursuits that are meant to kickstart conversations and shatter preconceived notions. We spoke with Robbins about all of the above in a lengthy face to face in New York recently, rolling from his thoughts on separating himself from his work to the lessons learned on Shawshank, his new documentary (45 Seconds Of Laughter), and his theater company’s efforts to put historic precedent back into the immigration debate.

What was your interest in reentering the world of Stephen King and what was it about this character that stood out or seemed like a challenge?

I didn’t really think about it that way because they’re such wildly different stories. For me, they exist on different planes. I didn’t really think about it. I watched the first season of Castle Rock. That and reading the first couple of scripts of the new season were what drew me to it. It’s a character I haven’t really done before. He’s morally complicated and possesses secrets about his past and other people’s pasts. He might be the one person in Castle Rock that truly remembers what’s happened there.

The family aspect is so important to this character. Can you talk about that?

Well, when you’re a criminal, when you run a crime family, your children are going to have morals that reflect that. I think his one hope for redemption is his daughter, Nadia, played by Yusra [Warsama]. It’s a complicated world that Pop is facing. He knows he’s dying and he only has a certain amount of time left. How do you rectify the actions of your life in a way that leads to a death that is whole? I’m not implying that he dies, by the way. I’m saying he’s dying. It’s like some people have deathbed confessions, some people change their whole existence when they know they’re dying. Some people resist it completely and deny it. I was interested in playing a character who was dealing with this ticking clock.

Obviously, you’re not dying… I hope.

Well, we’re all dying. From the time we’re born, we’re dying.

That’s very true, yes. Is that something that resonated with you: the idea of legacy building and looking back at the past?

Not really. I’ve learned how to separate the characters I’ve played from my own existence. I don’t really draw a lot of parallels between Pop and me. I suppose if I wanted to do that mental exercise, I could. I think it’s important as an actor to allow a distinct difference between you and the roles you play. I think it’s healthier.

Onscreen or offscreen healthier?

Both. For example, if you’re playing a morally ambiguous person, you have to allow the negative or you’re not playing the role properly. Oftentimes what some would do is, “Well, I don’t want to come off that way.”

There’s sort of a wink and a nod to the audience that they’re not [that person]. Almost like they’re protecting a brand.

Exactly. I think it’s best to just draw a line, to say, “Here’s what Pop is, and who I am is irrelevant.”

Is that a philosophy that was found in time through exploration or past work?

I used to hold on a lot more to the emotions of the characters that I would play. I remember when I was doing Jacob’s Ladder, what a dark time that was for me, because there was so much every day… A struggle between life and death and demons. You take that home with you, and it becomes a very hard thing to do for four or five months. I’ve learned over the years to leave it on the set and pick it up the next morning.

Objectively, that sounds like maybe a better idea. Specifically connecting back to the world of Stephen King, what were your main takeaways from working on Shawshank Redemption and how did that transform you as an actor?

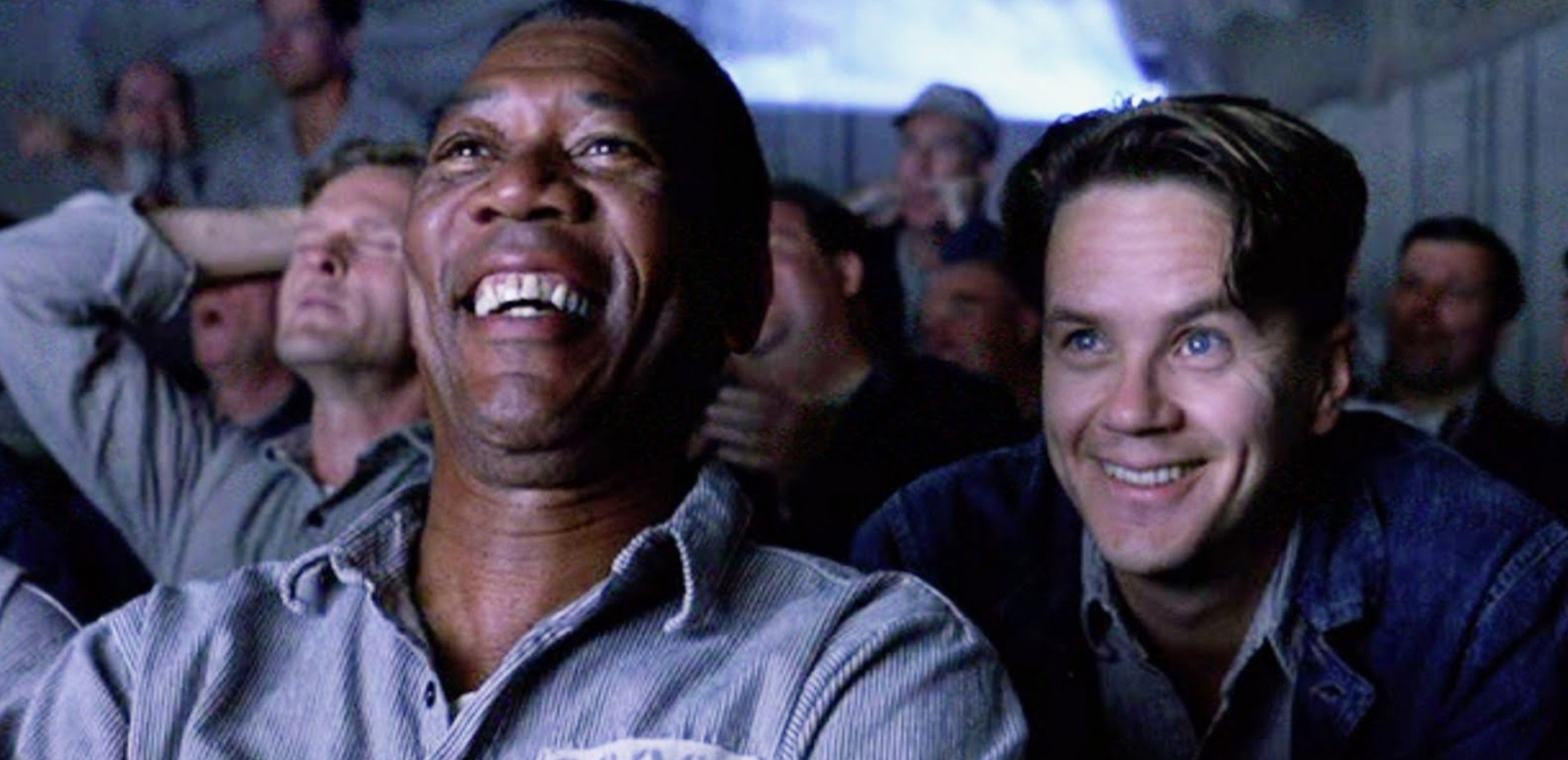

I guess it taught me to trust my instincts more. It was a really great experience for me to work with Morgan Freeman and Roger Deakins, Clancy Brown, and all the other actors. Frank [Darabont] had written the best script I’d ever read. When I think about that film, I think about what it felt like shooting it. It was long. It was difficult at times.

Physically? Mentally?

Both, but in the end, you only struggle with things you care about, and everyone on that film really cared about that script, because it was an amazing script.

Do you read Stephen King’s books?

I have in the past. Recently when we started this one, I read his stories that involve Pop Merrill. I love him as a writer. The Shining blew my mind when I read it in my 20s. I like his book on writing right now. Listen, he’s capable of such a wide array, writing in so many genres while being so prolific.

I did want to talk a little bit about your documentary, 45 Seconds Of Laughter. What’s the goal when you set out to do that project? What do you want people to take away from it?

Well, I’ve been working inside prisons for 13 years now. First of all, when the average person thinks about prison… let me start again. I don’t think we think about this at all.

Yeah, I think that’s accurate.

I don’t think we think about what we’re doing at all. It’s kind of like the death penalty. We allow it in the abstract, but we don’t want to know the specifics. We don’t want to know anything that challenges our world view on that. It’s barbaric.

Yeah, it is, definitely.

It’s premeditated taking of a life, and we ask agents of the state to be murderers.

Which is the part that I’m personally most uncomfortable with, giving that level of power to the state.

Well, you see, you give the power to the state, but who carries it out? The working man, the guard. And how dare we, as part of his responsibilities to his job, make him participate? But the reason it’s in the abstract is because if we knew the specifics of it, we would not tolerate it. This industry is one of the strongest purveyors of the myth of what incarcerated people are like, everything from the way we portray incarcerated men and women in movies and television shows, to the MSNBC Locked Up documentaries that… “Ooh, scary place! Violent, horrible people!” Listen, prisons serve a function. When you do something wrong, there’s no doubt in my mind for certain crimes that you should be incarcerated. By the way, there’s no one in prison that would object to that. It’s the length of the prison terms that we’ve been keeping a blind eye to, including people that I’ve worked with that when I first started working in prisons were serving life without parole for possession of drugs or gang affiliation. Then we had some propositions passed in California that changed the sentencing for the three-strike laws and changed the sentencing for juvenile offenders. Now all these people that had been living without any hope of getting out now had a possibility to get out. You ask about the documentary, the reason I did it, and what I would love for an audience to take away from it, is to see what we’re doing, see who we are incarcerating in a way that isn’t the typical portrayal that we see in entertainment and in the news.

I haven’t seen the film yet, I’ll be honest, but from what I’ve read, it seems like that’s not a focus. That you sidestep that and focus on the people.

Every person is worth more than their worst act. When we go in, we don’t ask what they’ve done. We don’t want to know because we’re dealing with the future. Pretty much everyone that’s inside is going to get out at some point, and we have eliminated in many states even the idea of rehabilitation. We ask our prison guards to deal in a punitive way every day with the people that are incarcerated. That dehumanizes them. It’s one of the highest suicide rates in the country — correctional guards.

I didn’t know that.

Think about it. They’re asked, as part of their job, to dehumanize the people they work with, and that has an effect on you. It has a really negative effect on you. We don’t provide any guidance for them to deal with those kinds of issues. [And the prisoners] we are propelling them forward with no rehabilitation and thinking, well, when they get out, what do you think is going to happen? They’re coming into your neighborhood. Don’t you want them to come out of prison with better tools to deal with disappointment and frustration than when they went in?

I’ve heard about other programs that incorporate art and music. It’s interesting how they play a role in rehabilitation.

Well, all of it had been eliminated when we started this. They had zero in the California budget for arts in corrections. We were able, through lobbying, to reinstate it into the state budget, but we only were able to do that with the help of conservatives voting for it. We had gotten a great deal of Democratic support, but it was only the support of the prison guards union. One of their officers who was watching the vote go down for arts in correction, it was being defeated, and he reached out to two state senators he knew on the right side of the aisle and said, “We want this.” They changed their vote, and we were able to get $1 million put back in the California budget. Not a lot. Then we recently got it up to $8 million. It had been completely eliminated out of the California state budget, and that’s a progressive state.

It’s been 20 years since Cradle Will Rock. You do this film, I know you’ve directed some TV episodes, but is this your future plan? Is it more on the documentary side of things?

I’ve got a couple other docs I have been imagining. I have a lot of footage for one of them. Listen, 45 Seconds Of Laughter is completely self-financed. I would love to have a budget for the next one, but I have come to understand that the stories that I want to tell… well, at least this story that I wanted to tell, 45 Seconds Of Laughter, wasn’t something that people saw as something that could make money. It’s sad that so much of the business is driven by that, by the market. When I was coming up, there were still a few madmen left running studios, ready to gamble. That was a cool time to be around because people took chances. I think everything is kind of pre-marketed now.

I remember I had a meeting with Milos Forman not far from here. It actually might’ve been in this hotel. He was about to do this movie. He wanted to work with me. And I got to the meeting and he said, “I’m not going to do the movie.” I said, “Why not?” He goes, “I was just in LA, and I went to a meeting with the financiers at the studio, and they showed me the poster, and I said no.” They were telling him how to make the film and he said, “That’s not the way you make films.” How many people have the integrity to say no?

And not make those little micro sacrifices.

Right. When you live in a spirit of compromise and you create in a spirit of compromise, it’s very difficult to make something that resonates as something fresh and new. Now, there still are those people out there. I just saw a movie last night or yesterday that Todd Haynes just directed called Dark Waters. It’s fucking awesome. Mark Ruffalo is amazing in it. It’s a movie about something that’s going to stir up a conversation, and I’m so proud to be in it. I wish there were more of those kinds of movies.

We’ve seen it to some degree, but I think you see so many outlets for content and you wait for a flood of that kind of thing; of more creatively driven projects coming to fruition. But at the end of the day, it’s a money-making endeavor, I guess.

Well, what I decided to do quite a few years ago was, I realized I have a great resource. I’ve had a theater company for 37 years now. When I’m done with a project, acting in something, I go into a laboratory and I make something new. I do it every year. That’s what’s been guiding me and driving me in what I want to create as a writer and a director. There’s no one saying no to me at my theater company. There’s no one saying, “Well, we don’t have the money for this.” That’s a genuinely unique and fortunate place to be.

A couple of years ago, I created this piece called The New Colossus. I took 12 of my actors who all were from different parts of the world, and I developed a piece about immigration and what it is to be a refugee. I asked each of these 12 people to tell the story of their ancestors. Their answers just journey from oppression to freedom. It’s 12 different time periods, 12 different languages spoken, 12 different journeys all at the same time. It ends with a plea to the audience. They’re all asking to be let in, and the audience has to decide whether they’re going to let these people into the country or not.

It’s stirring up these really great discussions. You start getting into these discussions, people start telling their stories… there’s one story, in particular, with this old woman who says, “I want to tell you a story about an American soldier.” She says this man was liberating Buchenwald concentration camp, and he saw this woman, and she started to stumble, and he rushed towards her before she fell. And his Sergeant says, “Stand down, Private.” And he ignored his sergeant’s orders and caught the woman before she fell. And he carried the woman to the medic. And the woman, she said the soldier got into trouble, but after he was admonished, he tried to visit this woman in the field hospital. She says, “That was my mother and father.”

Wow.

We get this all over, whenever we do it. We were down in South America and did it, and their whole experience is similar to ours. There’s immigration and refugees, and they start understanding that the DNA of America is exactly that. It’s people that made the choice first of all in the home country, to say, “I will not tolerate this anymore. I cannot morally tolerate this. It’s too dangerous. I don’t agree with the way things are going here.” And then had the courage to leave. Risked death. Some didn’t make it even past that first border. Then you consider the journey that they had to take to get to the boat or the plane or wherever they had to go. Mostly long journeys on land, across water, to get to a place where they could get to a boat that could take them somewhere. Survive that journey. Land with nothing and still survive. That’s our DNA. We’re descended from that strength, and to deny that is stupid, because there’s something unique and fantastic about that.

We did a matinee for a school in LA, and in the lobby of the theater we have a map, and we ask people to put magnetic pins on where their ancestors are from. And usually every night the world was represented. Not every country, but all across. So this day was unique because it was all Mexico and Central America. And we had a great discussion about what it is to be an immigrant or a refugee. And I remember it coming up, the way that it’s being talked about now. The rhetoric around this is so ugly, so divisive, so full of hate, that one of things that we want to do with this play is redefine how we think about immigrants and refugees. And I said to these kids, I said, “Listen, when you think about your parents, if they’re the ones that made the journey, or if you think about your grandparents, you have to understand, you have your own story to tell, and that there’s a great nobility in that story. There’s a great strength and a great courage in your ancestors to have made that journey, to make your life better, to make their lives better.” That is a story of heroism. It’s a hero’s journey. It’s risking everything, risking your life because you would not tolerate the circumstances you were in, and you wanted to make life better for your son, your daughter. I’m sorry, that is the story of a hero.

‘Castle Rock’ is streaming on Hulu with new episodes premiering on Wednesdays. ’45 Seconds Of Laughter’ is playing on the festival circuit. To learn more about ‘The New Colossus’ and Robbins’ Actor’s Gang theater company, go here.