Fashion has always been political, and the protest tee has been a staple in closets around the world for decades. Vivenne Westwood used tee shirts to promote anarchy and spark a British punk rebellion in the 70s and 80s. Katherine Hamnett pushed political agendas and advocated for worthy causes with bold block lettering. If first impressions are everything and clothes tell a story, shirts emblazoned with slogans are a way to let the world know what you stand for without saying a word.

Like any other popular clothing item, protest tees were always due for a comeback. But their recent revival says more about our social and political climate than it does about cyclical fashion trends.

“It was just this moment of like, ‘Wow, fuck you.’”

That’s how Amanda Brinkman explains her inspiration for the most visible protest tee of 2016. Brinkman’s “Nasty Woman” shirt came after the art curator decided to vent her frustrations during the presidential debates by experimenting with her newfound love of graphic design.

Brinkman took the slur Donald Trump directed towards opponent Hillary Clinton and put her own cheeky spin on it – wrapping the insult in a pink heart on a plain white tee.

“For me, that was an even bigger fuck you,” she says. “I’m going to make this fun and sweet and you can go fuck yourself.”

After posting the design on her shop Google Ghost, Brinkman shared it on Instagram, and woke up to over 20,000 emails and the news that the story of her shirt had been picked up by New York Magazine and Teen Vogue. She’d officially gone viral.

This story isn’t particularly uncommon in the Trump Era. From Etsy shop owners to sellers on sites like Redbubble and Tee Spring, savvy designers and budding brands have been capitalizing on the outrage our president stirs up.

Redbubble CEO Martin Hosking notes that the website currently houses more than 33,000 Trump-related images on retail items — with covfefe causing a recent spike in that number.

“About 40% of all sales come from works that are less than one year old,” he says. “Political memes are one of the drivers of sales.”

Dawnn Karen, a fashion psychology expert at the Fashion Institute of Technology says that the polarization our president stirs up has left people more comfortable sharing political views.

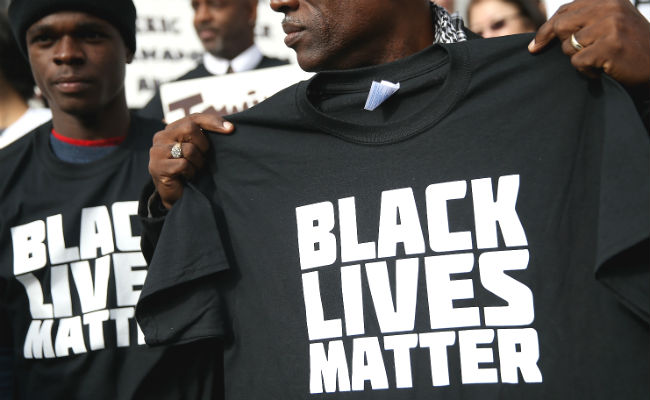

“People are being a bit more fearless with their political decisions,” she says. “They also want to belong, to have a sense of community. If they wear a shirt that says, ‘Black Lives Matter,’ they want people to know, ‘Hey, I belong to this community.’

But these opportunities to connect to like-minded people and share allegiances don’t come without a cost.

Catwalk Campaign Promises

This year, New York Fashion Week felt more like a political demonstration than the usual parade of silks, chiffons, and cashmere we’ve been treated to in the past. Instead of gilded gowns, oversized coats and velvet pantsuits, models walked down the aisles wearing t-shirts that read “People Are People” and “Feminist AF.” It all seemed well-timed to our current political moment, but the feminist resurgence in haute couture actually began a little earlier.

In 2014, Karl Lagerfeld staged a faux protest rally for Chanel’s Spring 2015 runway show. The event featured influencers like famed model and Lagerfeld muse Cara Delevingne brandishing posters that read “Women’s Rights Are Alright” and “Ladies First.” Then, in 2016, Maria Grazia Chiuri presented her debut Dior collection in Paris. The show marked the first time a woman had led the design team for the fashion house and Chiuri chose to use her inaugural outing by taking a definitively feminist stance – having models wear tees affirming the “We Should All Be Feminists” declaration made by Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie during her famous Ted Talk.

Both designers were touted as revolutionary and critics and fans alike praised their bravery and boldness on social media. But the history of the brands and their practices made these quasi rebellions feel more like publicity stunts. Lagerfeld has made headlines before for his misogynistic views. He’s fat-shamed artists like Adele and stated his belief that curvy women don’t belong on the runway. He’s also been accused of cultural appropriation by sending models down the catwalk in Native American headdresses. Similarly, Dior, a brand that scored a 0 on Fashion Revolution’s 2017 Transparency Index after failing to offer any information about their supply chain or production practices to consumers, marked their feminist apparel at $700 per shirt. Months after the shirt hit the runway (and got some flak from fans for its price tag), Dior announced they’d be partnering with Rihanna to donate a portion of the proceeds from sales of the tee to the singer’s charity. It came off like a half-measure, at best.

With a muddled history of co-opting activism, this year’s designers at NYFW had the opportunity to, as ethical fashion activist Amy DuFault says, “quit bullshitting us.” The writer and communications director at Brooklyn Fashion + Design Accelerator, saw the protest tee trend take off after Trump’s inauguration during the historic Women’s March in D.C.

“It’s this perfect storm between the Women’s March, Black Lives Matter, the climate march…” she says. “It’s been a hailstorm of people being pissed and every time someone’s angry, they put it on a tee shirt and they don’t ask how the tee shirt is made.”

DuFault decided to investigate where the shirts for the march were coming from by emailing friend and founder of Manufacture New York, Bob Bland. Bland had designed her own Nasty Woman tee for the Women’s March and DuFault wanted to know where the official shirts for the historic event were being produced. A company called Bonfire was in charge of providing the tees and, according to a Broadly article, they were asked to ensure the shirts were made in the U.S. They decided to go with American Apparel, Bayside Apparel, and Royal Apparel inventories, but that presented even more problems because American Apparel had recently been bought by Gildan, a Canadian manufacturer that’s been accused of mistreating its workers in its factories in Haiti and Honduras. The company provided “I Can’t Breathe” shirts to several NBA players protesting the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown three years ago before these accusations of labor violations came to light.

When feminist slogans started appearing on the runways in New York, DuFault snapped into action again. She contacted designers like Christian Siriano who built his show around a “People Are People” slogan and Prabal Gurung who endorsed the motto “The Future Is Female” with his line. Plenty of the designers announced that they’d be donating sales from their shirts to charities like Planned Parenthood and the ACLU, but DuFault wanted to know where the clothes were coming from.

In short, DuFault worried that the fashion industry’s new protest tees were being produced by women in developing nations, working long hours for less than a living wage.

“The amount of money Planned Parenthood and the ACLU keeps accepting from these companies off the backs of women has got to be called out,” she says. “There has to be some mending in the equation.”

Designers like Prabal Gurung and Jonathan Simkhai promise that their products were sourced in the U.S. or were made by workers receiving fair wages. Gurung notes that he was inspired by the Women’s March to use his platform for change.

“We had the idea to take the words of real women, the million women who marched, and use them to make a statement to inspire dialogue at and around our show,” he explains. “The essence of who a woman is has always been at the forefront of our designs and our brand, and now more than ever felt like the time to highlight and celebrate the exuberance of being a woman while leaving a lasting impact.”

The brand affirmed the shirts were produced locally in NYC and that a portion of the proceeds were going to the ACLU, Planned Parenthood, and Gurung’s foundation, Shikshya Foundation Nepal.

While some designers were forthcoming about their practices and policies, others refused to answer DuFault’s questions.

“When you’ve sold tons of t-shirts already, who wants to say, ‘Oh my god, I’ve done something wrong,” DuFault says.

Jag Beckford, the creator of Rainbow Fashion Week, says that kind of appropriation by the fashion industry shouldn’t be surprising at this point. Beckford founded Rainbow Fashion Week four years ago after being dissatisfied with her industry’s willingness to give back. She also saw a need in the LGBTQ community that wasn’t being filled. Her week-long event merges fashion with activism, promoting social justice issues while touting inclusivity and the importance of ethical practices when it comes to creating clothes.

She says the reason some luxury brands like the ones participating in NYFW can get away with adopting activist issues and turning them out for profit is because the audience they’re marketing to isn’t affected by the same problems they’re sporting on their t-shirts.

“If you look at the brands that are doing that, they’re never speaking to our market to begin with,” Beckford says. “They’re not speaking to the urban market. They’re not speaking to the middle class. Look at who’s sitting in the front row, those are the people they’re speaking to. They’re just waiting to get those dollars to purchase their outfit to give them the visibility in a red carpet event, to give them the name brand recognition, to increase their sales.”

Beckford, who actively fights for diverse representation and ethical standards during her own show, says brands boasting feminism usually aren’t practicing what they put on their tee shirts – in the models they choose to showcase and the methods in which their clothes are made.

“When they’re making a choice to include a person with a handicap or a transmodel, it’s [for] the shock value,” Beckford says. “They’re not lending their consciousness to any of those things. It’s whatever is happening in the moment, and that’s pretty much it.”

Following The Chain

The internet may often get accused of being a cesspool of trolls and fake news, but for fashion brands, it’s also a lie detector.

“The beauty of the internet is that you can’t really hide anymore,” DuFault says. This has proven especially true for clothing manufacturers.

The Fawcett Society learned this fact first hand when their shirt “This Is What A Feminist Looks Like” — created in collaboration with Elle UK and worn by Emma Watson as part of her #HeForShe campaign — was flooded with negative press. Reports indicated that the tee was made by women in Mauritius earning less than a dollar an hour and living in extreme working conditions, though Fawcett claimed those allegations were unfounded and that they were investigating the matter.

Sarah Ditty, who works as the Head of Policy at Fashion Revolution, a not for profit company committed to pushing for greater transparency in the fashion industry, says that it’s women who often suffer the most when these kinds of clothing campaigns are launched.

“80 percent of garment workers are women who work in tough conditions,” she says. “They barely make minimum wage and have very few rights. It’s only thinking about one side of the equation which is so ironic when it’s feminist t-shirts.”

Fashion Revolution was launched after Rana Plaza, a building that housed five factories producing clothes for some of the world’s biggest brands, collapsed, killing over 1,100 garment workers. It was the fourth largest industrial disaster in history and most of the victims were young women.

Ditty’s organization started a Transparency Index that probed both fast fashion and luxury brands about their manufacturing practices and production policies. The report ranked 100 of the biggest global fashion and apparel brands and retailers according to how much information they disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impact. Only 32 of the 100 brands surveyed disclosed their supplier list and no brand scored above a 50% on the index.

Ditty says finding tangible evidence of the ethical impact of brands is nearly impossible for the average consumer.

“No wonder it’s so difficult to make an informed decision,” she says. “You can’t really find relevant information. Most of what’s put out there is based on values and beliefs so then it becomes a matter of trusting that brands are holding true to their values without sharing any actual information to prove that in practice.”

Like so many of our current societal struggles, Ditty sees the speed-of-light pace at which we live as part of the problem. Information takes too long to sort through, especially in an era of rampant consumerism.

“There’s a problem with the sheer number of products that are made and sold at the speed they’re [being] sold,” she says. “We need to tackle mass consumption, to educate people about different ways of consuming that don’t always involve buying loads of shit.”

Wearing The Change

One way brands can disrupt the status quo is by changing their intentions, that’s what Emma McIlroy did when she created Wildfang, a startup brand, with her partner Julia Parsley. The pair, who previously worked at Nike, decided to fashion their own tomboy-centric clothing line for women who felt neglected by the industry.

They started crafting oversized tees and blazers for women. The idea was to cut lines that didn’t feel so in line with the fashion industry’s traditional notions of femininity, but it was their own office culture (and the input of their fans) that pushed them to start crafting feminist wear. The brand sent out surveys asking a simple question, “Are You A Feminist?” The responses they got back were so misinformed; they decided to address the problem through their clothes.

“Right now, if you’re a brand like us, where your main mission is to service a strong independent woman and to make her life better, then it’s really hard to not be having conversations about her life beyond style,” Mcllroy says. “The world is a shitshow right now. Her rights are being attacked in so many ways – immigration, women’s healthcare, equal pay. If we’re not having those conversations, we’re not servicing her.”

The brand dedicated its efforts to not only making clothes with a message, but backing up that message with diversity amongst its models and donations to nonprofits that are working for change.

“We work really hard to hero women of color and queer women,” Mcllroy says. “Those are the women that get the least representation of any of us. That’s a big part of our focus, ensuring that representation exists and that those women get a platform.”

Mcllroy says the brand will give nearly $100,000 to charity this year but, more important than their philanthropy is their willingness to be honest with their fans.

“Our team fails on a daily basis,” Mcllroy explains. The company sold a Michelle Obama pin that garnered pushback over concerns that the first lady’s skin tone was purposefully lightened.

“We issued a public apology on Instagram and returned all inventory to the vendor and had new pins made which more accurately reflected Michelle in all her glory,” Mcllroy says. “We don’t celebrate failure but we acknowledge it when it happens and we talk about it rather than hiding it or spinning it. We’re transparent with our fans. It’s important to have a culture of transparency and a culture of learning; we aren’t perfect, but our community makes us better.”

Ultimately, what most critics and brands agree on is the need for open dialogue across the industry. If fashion wants to stand for something, it’s going to have to take a broad approach.

“If you can’t see it, you can’t fix it,” Ditty says. “What we want to see is a cleaner, a safer, a fairer, a healthier fashion industry for everybody across the entire value chain, from farmer to consumer and those who work in the end of life products and everybody in between.”

That means upending a business that’s complicated at best and, at its worst, intentionally negligent for the sake of profit. High-end brands must figure out a way to come clean about the source of their products while protecting the names they’ve spent decades building up. Fast fashion companies – the Forever 21s of the world – and online t-shirt vendors need to figure out how to offer their product at a rate that’s still competitive but that doesn’t come at the cost of the garment workers sewing their clothes. Because the price of fabrics like cotton fluctuate seasonally, brands have discovered that the easiest way to control costs is to underpay and overwork the labor source. Obviously, there’s nothing revolutionary about that.

The fact is, if you’re touting activism and aligning your company with empowering messages that take a stance on social justice issues, the easy way out isn’t going to cut it anymore. There are watchdogs like Fashion Revolution in place and consumers want to buy from brands they can trust. In this highly politicized landscape, people also want to feel like the products they’re buying and who they’re buying them from align with their own political beliefs. Social media has made it nearly impossible for brands to simply bandwagon worthy causes.

Still, consumers still have room to evolve in the era of wokeness. Buying clothes, just like buying food, is a two way relationship.

“Just be aware where things are coming from,” Amy DuFault says. “If you’re going to wear how you feel on your chest but not do the research, to me, that’s worthy of shaming.”

And if you’re a brand hoping to capitalize on our collective wokeness? It’s time to put your money where your mouth is.

“I think, in the era we live in, there’s this wake up call for a number of brands that have positioned themselves as being more liberal or progressive,” Mcllroy says. “People want to know what we’re doing beyond just selling clothes.”