Vince McMahon’s unmistakable voice boomed through the room, as if he was addressing tens of thousands of screaming wrestling fans. “The XFL will be a tremendous success,” he promised the much smaller assembly of media at his new football league’s introductory press conference on Feb. 3, 2000. He flashed his trademark arrogant grin as he vowed that the “No Fun League” was about to meet the “Extra Fun League.” Some people thought McMahon was crazy, but some people believed him, because he is undoubtedly one of the greatest ringmasters in entertainment history.

We laugh at these statements today, obviously, because the XFL is synonymous with failure, perhaps more than any other sports league that ever folded. The USFL? Arena? World Football League? United Football League? All failures, yes, but none as spectacular and legendary as McMahon’s epically oversold dud. The rise and fall of the XFL was so astonishing that it’s hard to believe it has taken this long for ESPN to produce a 30 for 30 that delivers the behind-the-scenes drama of a figurative blimp crash that was highlighted by an actual blimp crash.

Directed by Charlie Ebersol, the son of former NBC Sports president and XFL co-founder Dick Ebersol, 30 for 30: This Was The XFL is a fantastic blast of nostalgia that takes fans inside the ultimate byproduct of the over-the-top, Michael Bay-inspired, testosterone-driven period of the late-90s and early aughts. Or, basically, the WWE’s “Attitude Era.” But there’s so much more to this 30 for 30 than simply a tale of two men who promised more than they could deliver. It is a “love story” about two friends whose bond couldn’t even be broken by the loss of millions of dollars, and it is also proof that the XFL deserves far more credit than it has ever received for its impact on today’s NFL.

“They got what they paid for.”

“My intent from day one, when I pitched this to ESPN, was to do a film about the love story between my father and Vince, and their 30-year relationship that started with Saturday Night’s Main Event and culminated with the XFL,” Charlie Ebersol tells me. “This is the story of two guys who, basically, anything they’ve ever touched has turned to gold, and they have this one thing that the public largely views as a failure, and yet somehow, the most shocking part for anyone, their relationship survived. In Hollywood, I can tell you, relationships don’t survive someone showing up late for lunch, and for the XFL to be an unmitigated failure to the public, and yet these two remain best friends, I think speaks to a much larger relationship.”

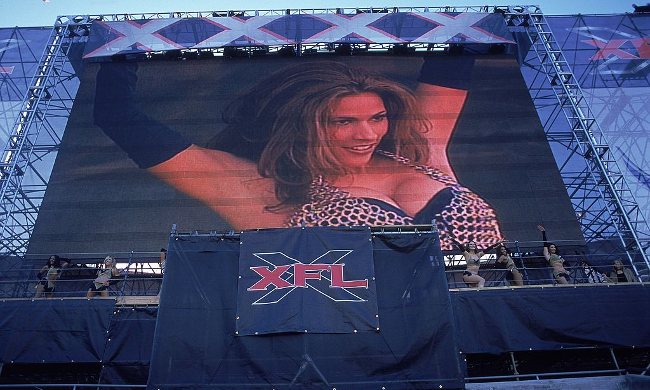

Make no mistake, This Was The XFL is just as much a comedic tragedy as it is a love story, and it is excellent in its entirety. Without giving any of the film’s revelations away, everything, from Vince’s wild idea for truly violent football — “This will not be a league for pantywaists or sissies,” he snarled at the press conference – to a last-ditch effort to bring in viewers by “invading” the cheerleader locker room, is covered. Bob Costas even offers hilarious insight into his legendary face-to-face interview with the WWE chairman. It is simply a must-watch for fans of both football and schadenfreude.

Charlie is the right man to tell this story, because he was in the locker rooms of the WWF when his father and McMahon first teamed to create a pro wrestling institution, and later, as a teen, he watched and learned as they brought the XFL to life. And he certainly knows, perhaps better than anyone, why it crashed and burned.

“Their biggest mistake is that they spent so much time marketing and so little time on the players,” Charlie says. “The players only had 30 days to practice and they ran commercials for six months. If they’d reversed that equation, I think they would have been much better off. I don’t think they realized how big the gulf was between what they were promising and what they would actually deliver. They say you get what you pay for, I mean, they got what they paid for. They were promising the NFL and they were delivering the World Football League.”

That’s not to say that the XFL was the absolute failure that it has been labeled for so many years. Yes, it lost money. A lot of money. But NBC would have lost even more money had it reupped its deal with the NFL, and the only way Dick and the network wouldn’t have lost money would have been to simply give up. Instead, Vince, who always has an ear on the audience, sensed a need from the fans for a league that allowed its players to have personalities. Dick, on the other hand, saw an opportunity to keep football on NBC and control every aspect of the finances. The league would own the teams, and the network wouldn’t have to buy rights. On paper, this seemed brilliant.

“The NFL, leading up to the XFL in those eight years, ’94 to 2002, radically changed its position with networks. It used to be that every year was a four-year deal and by the fourth year the network was making money,” Charlie explains. “In 1994, when Fox wanted to get involved, they agreed to pay so much money that they would lose money every year, with the understanding that the NFL would validate their system. And it did, because Fox is a major player now because of the NFL. NBC had never lost money from airing a sport. The NBA, NFL, Olympics – all of them were on NBC in 1996, and they were making money. When the NFL came to my dad in ’98 and said, ‘You have to pay $500 million a year,’ which meant that they would lose $100 million a year — $400 million over the course of the deal – my dad just thought, ‘This is crazy, we’re paying for rights and we don’t own anything. After four years, we just have to renegotiate with the NFL to get these rights.’

“His thesis was,” Charlie continued, “if I can create a league where I own the league, it’s worth betting $50-100 million over two years, because if I own it and it works, I won’t have to pay rights fees again, and I’ll make a lot of money. That’s why when people say, ‘NBC lost so much money!’ I always chuckle because NBC lost $37 million on the XFL, and the same year, CBS and Fox lost somewhere in the neighborhood of $120 million each.”

“Whether they add different rules or not, it’s still football.”

“@HeHateMe BAY-BEE!”

Here’s a first look at our upcoming film, #ThisWasTheXFL! pic.twitter.com/m7Ks1HERoK

— ESPN Films 30 for 30 (@30for30) January 26, 2017

Another aspect in which the XFL isn’t necessarily a complete failure is what it meant to the players. These guys were rushed into a whirlwind process, and they had to live up to the ridiculous hype that was boosted by hilarious television ads that featured tanks, mine fields, and a guy being hit by a wrecking ball as the narrator promised, “No fair catches!” The XFL was essentially promising that players might actually die on the field, but, in reality, these guys were lucky to be completing passes. Each team had two months of practice and one scrimmage before they took the field for McMahon’s smash mouth football, “the way it was meant to be played.”

But for a ton of undrafted free agents and NFL castaways, it was a second chance. It didn’t matter if it was a gimmick, or if the quality of play rivaled an adult flag football league. It certainly didn’t matter that they were paid a flat fee per game, and earned bonuses for touchdowns, big hits, and victories. It was professional football and an extra chance to impress NFL scouts. And what’s amazing is that the guy who would become the most famous player in the XFL almost never had a chance to make a roster.

“My agent, at the time, had another guy,” Rod Smart remembers. “He was a quarterback out of Michigan State, but I can’t recall his name. They were interested in him, and [my agent] said, ‘I have this running back as well.’ They said, ‘We’re not interested in a running back; we’re interested in your quarterback.’ He said, ‘Well, in order to get my quarterback, you have to take a look at my running back.’ We both went out for the workout and whatnot, and I blew them all away. They ended up keeping me and sending the quarterback back. Good for me, not too good for him.”

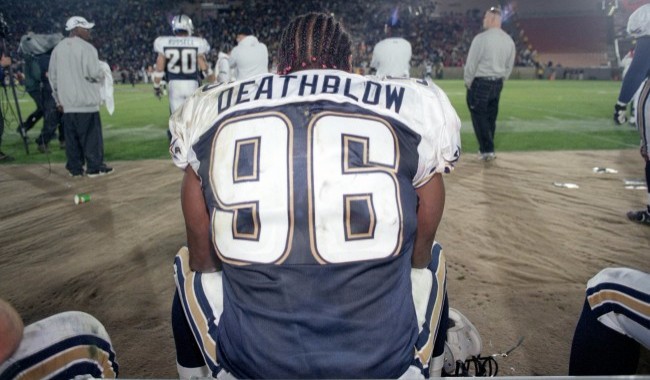

Good is an understatement. Today, mention the XFL and only one name still resonates: HE HATE ME. That was the nickname Smart had sewn on the back of his jersey, as one of the league’s creative quirks was showcasing the personality of the players, because it gave fans something to cling to. There were some great nicknames: Deathblow, Hit Squad, E-Rupt, The Truth, Chuckwagon, and Big Time. But the one that stood out from the moment the Las Vegas Outlaws took the field was He Hate Me, and it made Smart a household name in a league full of nobodies.

“To me, it was about football and the opportunity. Whether they add different rules or not, it’s still football. All that hype, you have to thank Vince McMahon, because he’s the guru of entertainment,” Smart says. “And I was able to establish myself in the entertainment as well, with my nickname, but I showed my skillset on the field as well. There were two guys for another team who put ‘I Hate He’ and ‘I Hate He Too’ on the backs of their jerseys, so they played into as well for a little notoriety for themselves. But by that time I had already put it on the map, way above the rest of the nicknames.”

When people talk about the legacy of the XFL and its contributions to today’s NFL, they begin and end with the sky cam. That’s unfortunate, because, as the film reveals, there is a lot of the XFL in today’s game, and some fans would argue that the “No Fun League” could still learn a thing or two from the XFL about personality.

Sure, the NFL is a massive, billion-dollar family brand, but that doesn’t mean players should be fined for dancing or wearing their hearts on their shoes. There is always a middle ground.

“I think that sports are meant to be fun and people underestimate the American public’s ability to differentiate the individual from the overall game,” Charlie says. “So, when they fine a player, they’re doing it to protect the Shield. I think they’re losing sight of the fact that individuals are what make fans. One of the reasons the NFL suffers and doesn’t have the giant personalities that the NBA has is because they don’t allow expressions of personality. The NFL made $12 billion last year. They’re not about to risk those partners. The XFL didn’t have to worry about that.”

“You should allow players to be themselves, to be able to show their personalities to the world and the fans,” Smart adds. “That’s what the fans love. They want to get in tune with their favorite players and understand them on a personal level, even outside of the NFL. But at the same time, the league has been around a long time, it will be around for an even longer time, and they make the rules. I’m pretty sure at some point they’ll probably change things and loosen up a bit.”

Smart was at a sports bar when he saw the ESPN SportsCenter report that the XFL folded after one season. Like any player that had used the XFL as a second chance, Smart was upset at the news. Unlike most other players, though, his XFL notoriety and performance helped him sign on with the Philadelphia Eagles and later the Carolina Panthers, where he spent four seasons. Smart says his NFL teammates and opponents never gave him a hard time about his roots in a failed gimmick league. Instead, they embraced it. Jake Delhomme even named one of his horses She Hate Me. Had things been a little different, though, Smart may have never developed that kind of bond.

“I always looked at it as my stepping stone to the NFL,” Smart says, “but if the league would have lasted, of course I would have stayed there a few more years to see how big it could get. I’m very thankful for it anyway, because it helped me be able to show my talents and show the NFL that I could compete on that level as well.”

“They were extraordinarily unlucky.”

Charlie remembers his dad reading “stacks and stacks and stacks” of Harvard Business Reviews about the USFL to understand what worked and what didn’t. It was from that league’s failure that Dick had the idea to have his league own every team, so that billionaire owners, like Donald Trump, didn’t ruin everything. The thing that Dick and McMahon missed, Charlie explains, was that the USFL still spent “real money” to sign guys who could have still played in the NFL. The XFL simply settled for guys that could play at all. That was the first big problem.

The other problem was just plain, old bad luck. It started with the very first game, as the XFL chose to make the debut primetime offering a contest between Smart’s Outlaws and the New York Hitmen. This proved to be a terrible choice, because, to be blunt, the Hitmen sucked.

“Three weeks before kickoff, they decided to make the Orlando game the B game instead of the primetime A game,” Charlie says. “They went with the Vegas game and that game turned out to be a 19-0 blowout, in which the New York team, I think, had 20 yards of total offense in the first half. The Orlando game was a barn-burner, 37-34, a good football game.”

One of the things that made the Orlando game so unique and memorable, too, was the opening scramble. Instead of a coin toss, McMahon’s sissy-less league had players race each other to grab the black-and-red XFL ball at the 50-yard-line. One guy, Vegas’s Jamel Williams, was the best in the league at the scramble, racking up six straight “wins” before someone finally beat him. Another guy, Orlando’s Hassan Shamsid-Deen, scrambled one time. It was his only play of his XFL career, because he separated his shoulder diving for the ball. Charlie calls that “the first major unlucky moment of the XFL.”

Another unlucky moment was the aforementioned blimp crash. It certainly didn’t help that some players and coaches had zero personality and/or refused to play along when on-field “reporters” and personalities like Jesse “The Body” Ventura used some pro wrestling tactics to try and win viewers back.

But nothing could top the ultimate moment of flat out terrible luck that was the dagger in the XFL’s heart. Not even Charlie knew the real story behind the primetime debacle that left Lorne Michaels reportedly enraged with NBC and Dick, the man he created Saturday Night Live with, until he got the major players to talk about it for This Was The XFL.

“I didn’t know the details and all the shenanigans that went on around Game 2, and how politically unsettling that game was,” Charlie says. “That was really shocking, and in the film it’s a great moment for the audience to discover what happens. To come off the high of Week 1 to what happened in Game 2 was just insane.”

He undersells the moment, but it’s hard to truly capture, in words, just how remarkably unlucky the XFL was on that fateful night in February. Fortunately, This Was the XFL allows McMahon and Dick, as well as a score of other participants in this weird, wild league’s woefully short run, to tell their story once and for all.

The newest 30 for 30 airs Feb. 2 at 9 pm ET on ESPN.