Quinn Nordin was just like every other celebrated high-school football recruit facing a high-pressure decision on National Signing Day. On Wednesday at a little after 10 a.m. local time, Nordin put pen to paper and faxed his National Letter of Intent to Michigan, counting as yet another big win for second-year coach Jim Harbaugh.

Everything stated above — a big-time recruit choosing a blue-blood program — seems normal, which is a paradox because the norm on signing day is to be as excessive as possible. (Puppies, cakes, and even sky-diving videos are what fuel the circus now.) And Michigan obliged by holding its signing day event, called “Signing of the Stars,” at the on-campus Hill Auditorium. Among those in attendance? Ric Flair and Tom Brady, of course.

So, when Nordin’s name was added to the Wolverines’ 2016 class, it was a huge victory for Harbaugh, who conducted a late recruiting surge for the No. 1 kicker in the country according to 247Sports composite rankings.

Yes, a kicker.

Quinn Nordin (@QuinnNordin) – the nation’s #1 kicker (https://t.co/eQllcdHDDH) is #NewBluehttps://t.co/rktdIeERdN pic.twitter.com/Ne0vo0U5a2

— Michigan Football (@UMichFootball) February 3, 2016

And, in that specific way, Quinn Nordin is actually nothing like every other celebrated recruit who faced high-pressure decision on National Signing Day.

***

You might have already heard the stories about Nordin without even knowing it was him. The most famous one involved his music video — yes, an actual music video set to Diddy’s “Coming Home,” featuring a private jet and everything — last June announcing his verbal commitment to Penn State.

Yup. That’s Nordin.

“He has that personality to where he draws attention,” said Brandon Kornblue, Nordin’s private kicking coach who has operated Kornblue Kicking since 2008. “He’s very confident in his abilities. A lot of what’s happened has been brought on by himself. When you do that, there are positives and negatives.”

Such videos aren’t common, per se, but they’re not as unprecedented as they used to be. In 2015, cornerback Iman Marshall committed to USC via a music video broadcast on Bleacher Report. But Marshall was a five-star prospect and the No. 4 overall recruit. Though he’s the top-place kicker prospect, Nordin comes nowhere near that type of classification. You’d never guess Nordin’s recruiting ranking — he’s considered the 693rd-best prospect in the country, per 247Sports — based on the kind of focus he’s received.

Understandably, recruiting curmudgeons viewed the video as validation that Nordin was just like every other self-centered prospect looking to make a name for himself. Turns out, nothing could have been further from the truth.

“There was a friend of his that came to him with that idea,” said Kornblue, who played at Michigan from 1995 to 1999 with future New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady. “It wasn’t Quinn’s idea. I thought it was super cool, but if there’s someone who doesn’t know him, it looks like a ‘look at me’ type of deal because kickers don’t normally do that.”

Was it excessive? It depends on your view, but part of being recruited is having fun with the process — especially when you play a position where no one knows your name until you make, or miss, a critical field goal. Kornblue agrees that while the process has been overwhelming for Nordin, he has enjoyed it all the same.

And for any grief Nordin took for the video, there were others, like Michigan’s star safety Jabrill Peppers, who were impressed by it.

I thought I changed the game w/ my poetic announcement on ESPN… Bro… a Kicker just hopped out a private jet for his commitment 😂😂😂

— JP5 (@JabrillPeppers) July 10, 2015

Nordin could have been a celebrity for a week before dropping back into anonymity. Then his name appeared again the headlines last month. Harbaugh was coming to Nordin’s home in Rockford, just north of Grand Rapids, Michigan, but this was no ordinary in-home visit. Harbaugh was sleeping over at Nordin’s house and spending the day with him. It was a tactic that, even by recruiting standards, was viewed as a fine tiptoeing job by Harbaugh on the line separating normal from uncomfortable. (Then again, Harbaugh’s M.O. is to walk that line in general.)

https://twitter.com/QuinnNordin/status/688025159387725824

It also happened to work. Chalk up a “W” for Harbaugh and his obsession to lock down a recruit of the non-blue chip variety. The stunts may be mocked, but the batting percentage is high.

However, recruiting is about exploring options and taking advantage of all the opportunities made available. For many prospects, the chance to be doted on to this extent won’t be possible for at least another seven or eight years. A small percentage of high-school football players across the country will receive a full ride Division I scholarship. An even smaller number will be drafted in the NFL. And a more select few will have options for a second contract.

In the meantime, Nordin lived it up.

***

The hoopla surrounding Nordin’s recruitment clearly makes for a unique tale. One could reasonably expect a five-star quarterback to be the center of attention, but a three-star kicker?

Certainly, access to Nordin feels more like a No. 1 overall recruit. Attempts to reach Nordin were unsuccessful and Ralph Munger, his former coach at Rockford High School, said only that he wishes Nordin “continued growth and the best of luck with whichever school he chooses” via an emailed statement.

None of this is an indictment on Nordin, of course. Imagine being a high-school senior with reporters and recruiting scouts blowing up your phone every day, wanting a quote or two about the biggest decision of your life to date.

That decision seemed like a sure thing as recently as a week ago. Nordin was verbally committed to Penn State, meaning he was under a non-binding agreement, and signing day was expected to be relatively quiet. Then, he tweeted at 7:36 p.m.

https://twitter.com/QuinnNordin/status/692521487308341248

“I believe the past path for my future and career no longer exists at Penn State,” Nordin said. “Therefore, I am decommitting [sic] and will be taking an official visit to USC this weekend. I will sign my national letter of intent on February 3, at 11 a.m.

“Thank you to Penn State coaching staff and the 107,000 strong,” he concluded, referring to the nearly 107,000 fans Penn State’s Beaver Stadium holds.

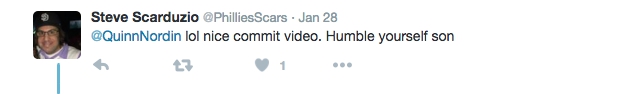

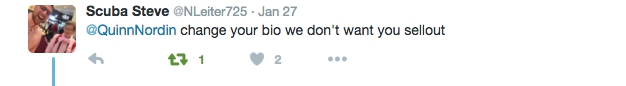

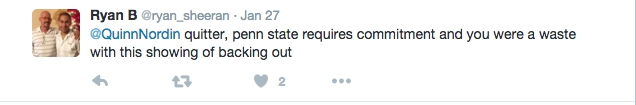

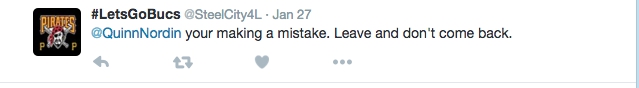

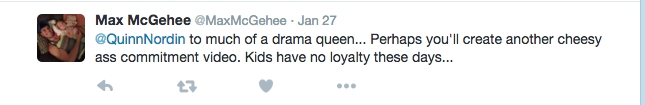

The reaction was mixed. Some wished Nordin well. Others were straight-up malicious. Recruiting can be glitzy, but there’s a nasty underbelly on message boards and social media, namely Twitter, where grown adults living vicariously through their favorite team message hateful things to teenagers. Using Nordin’s music video as ammo, critics took their turns firing a barrage of insults at the newly decommitted player.

Social media invites bravery of the worst kind. What feels like an easy sentence to write can be hurtful without one side ever knowing the consequence of their words. On the other end of those replies isn’t just a Twitter handle that exists on its own in a universe void of time and space. It’s a person trying to do what’s best for themselves.

Nordin did in fact visit USC on Jan 29. That came one week after he took an official visit, in which expenses for a trip to a campus are paid for by the school, to Baylor and two weeks after visiting Michigan. At the time of the interview, Kornblue said he expected Baylor coach Art Briles to be at Nordin’s house. (Briles’ visit fell during the “Contact Period” of the NCAA recruiting calendar.)

Last official visit for @QuinnNordin over the weekend. Coach Helton-led tour of USC's facilities last night. #Fab50 pic.twitter.com/a33RLydJC8

— Brandon Kornblue (@KornblueKicking) January 31, 2016

“Overall, he’s done a good job of it handling all the pressure,” Kornblue said. “All these coaches make it seem like he’s the best thing that’s ever happened to them. It’s tough mentally and emotionally for a 17-year-old.”

***

It wasn’t always like this. There was a time when Nordin was unknown in the recruiting world. At Rockford, he was actually known initially for his lacrosse skills, not his kicking. “He had some Division I offers” in lacrosse, according to Kornblue.

There are examples of kickers who began their athletic careers in rugby or soccer—you know, sports involving powerful legs. Lacrosse, on the other hand, is a new one. At 6-foot-1 and 200 pounds, though, Nordin is not built like the kickers movies and TV shows caricaturize. For all the emphasis scouting places on size and speed, the so-called “tangibles” of a traditional football player, physical appearance is also important when it comes to kickers. There’s a sense of assurance needed that they’re as much of an athlete as they are an owner of a reliable leg.

“The fact that he was a strong lacrosse player attracted a lot of coaches,” Kornblue explained. “They don’t like the stereotypical kicker profile, the guy who’s scrawny and soft. Kickers now are big and strong. Quinn really fits that profile and he can show off that confidence. He passed the eye test.

“That’s when a lot of the offers came, when they saw him in person.”

It used to be, too, that evaluating a kicker was as simple as asking one question: Did he make the kick?

Yes? He’s good.

No? He’s not.

It’s different now. The kicking percentages still matter, yes, but private coaches like Kornblue act as liaisons between prospects and college coaches. Kornblue specifically helps recruits with their highlight reels and social media presence, but he also provides context for what kickers like Nordin can do.

“College coaches feel comfortable recruiting and evaluating quarterbacks; they don’t feel comfortable recruiting and evaluating kickers,” Kornblue said. “Because college coaching staffs are limited with the guys they have — they can have nine full-time assistants — they don’t have a kicking coach, or someone who understands kicking at a high level, 99 percent of the time.”

The rise of private coaching for kickers doesn’t get the same recognition of, say, a George Whitfield, Jr., who has worked with quarterbacks like Cam Newton. But with special teams evaluation as limited as it is, these kicking camps and rankings can be invaluable. They teach everything from body and feet position to mental preparation.

“[Making a kick] can be sometimes the difference of one inch in where you’re starting,” Kornblue said. “You’re one inch too close or too far away from the football. It can be the difference in accuracy.”

There is indeed an explicit way to kick a football. The specifics cannot be overstated. For such a routine maneuver, pinpoint muscle memory can be the difference between a win and a loss.

Sometimes, the implications of that are much greater:

“I don’t teach every guy to kick like I did,” Kornblue continued. “I study the best guys in the world in college and the NFL and see what they do that’s similar. And it’s using that to make suggestions. And when you find something that works, you try to stick with it.”

***

Maybe it’s appropriate, then, that Nordin was as highly recruited as he was. Instead of pursuing lacrosse, however, he went all in with football because that’s where he felt his future was and it gave him the best chance to succeed. So, for the past few years, Nordin attended Kornblue’s camps in Michigan, Ohio and Florida, where Kornblue is currently based.

“Guys like Quinn don’t live close to me, but I’ve been able to coach them,” Kornblue said. “It can work, but it requires a large commitment and trust on their part.”

It showed. According to numbers shared by Munger, Nordin hit 14 of 19 field goals in 2013. He’s missed just four extra points in his career. His punting average increased from 37.7 yards per kick in 2013 to 52.9 yards per kick in his senior season.

To borrow a phrase from Alabama head coach Nick Saban, Nordin had to trust the process to get to where he is. From refining his craft to promoting himself on social media, every step of Nordin’s development has been carefully molded. Nothing has been by accident, but by no means has that predicted the path.

“Quinn is a very loyal personality,” Kornblue said, “so for whatever reason, he was willing to trust me throughout. I noticed he had the potential and ability to be a big-time kicker.

“But neither of us predicted that he was going to get this kind of attention.”