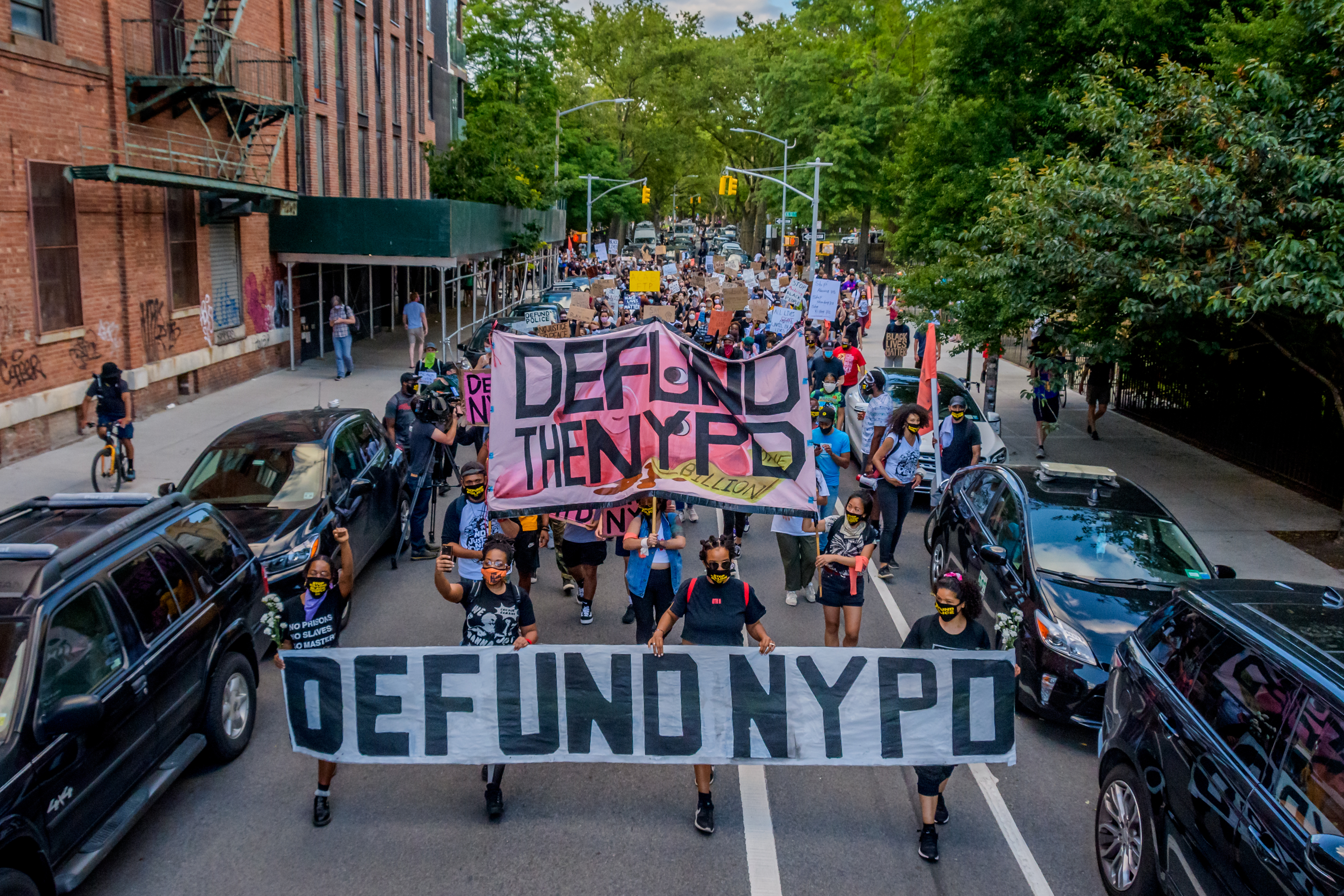

Whether you’ve been in the streets protesting police violence or merely looked at Twitter, like, once this past week, you’ve likely had the words “Defund the Police” enter your orbit. If your knowledge of the term begins and ends at seeing it on protest sign or as a trending hashtag, it may sound like a radical idea; more of a pipe dream than a potential policy. But while it’s doubtful that you’ll see defunding the police on the national ballot this November — President Trump is campaigning on a platform of “Law & Order” and the presumptive Democratic nominee, Joe Biden, has already signaled that he’s not for defunding the police — the idea seems to be gaining support in a hurry. As more and more people look into how much of a city’s budget is actually spent on policing, how small of an effect that has on driving down crime rates, and the tremendous number of tasks we rely on police officers for, we’re witnessing a paradigm shift in real-time.

This past Sunday, June 7th, the Minneapolis City Council voted to dismantle the city’s police department following George Floyd’s murder at the hands of officer Derek Chauvin with nine votes in favor, giving the city council a veto-proof supermajority. Speaking to CNN, Minneapolis Council President Lisa Bender said:

“We committed to dismantling policing as we know it in the city of Minneapolis and to rebuild with our community a new model of public safety that actually keeps our community safe. [We need] to listen, especially to our black leaders, to our communities of color, for whom policing is not working and to really let the solutions lie in our community.”

Though exactly what the replacement of the police force will look like in Minneapolis isn’t clear, the action wasn’t taken on a whim. The approach was looked at from both budgetary and community-based perspectives and the council clearly decided that they could create a better standard of living without traditional policing. It’s a massive moment in the history of the nation and, with NYC promising to cut the city’s police budget too, it very well may become a trend.

We are going to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department.

And when we’re done, we’re not simply gonna glue it back together.

We are going to dramatically rethink how we approach public safety and emergency response.

It’s really past due. https://t.co/7WIxUL6W79

— Jeremiah Ellison (@jeremiah4north) June 4, 2020

What does defunding the police mean, specifically?

In a very basic sense, when people call for the defunding of the police, what they’re asking for is “shrinking the scope of police responsibilities and shifting most of what government does to keep us safe to entities that are better equipped to see that need,” says Georgetown Law School professor Christy E. Lopez, in an article published in the Washington Post. “It means investing more in mental health care and housing and expanding the use of community mediation and violence interruption programs.”

According to Forbes, despite the fact that the level of crime has dropped substantially over the last 30 years, cities throughout the country allocate larger and larger shares of their budgets to law enforcement every year, and today collectively spend $100 billion a year on policing nationwide and $80 billion a year on incarceration. Part of the reason for these ballooning budgets is because of how heavily we rely on them as a society for handling issues that police aren’t trained or equipped to deal with.

Samuel Sinyangwe, the co-founder of Campaign Zero, a data-driven platform that seeks out comprehensive solutions to ending police violence, says we’re simply asking too much of them. “For too long, police have been used and invested in as a catch-all for a range of issues — from substance abuse to homelessness to even school discipline. That is way beyond what the role of the police should be.” Sinyangwe told The Philadelphia Inquirer, “Instead of police, we should be investing in alternatives. In response to public health issues like substance abuse, we should be having mental-health providers responding to calls involving people who are having mental-health crises rather than police.”

According to CNN, when the Minneapolis city council analyzed the 911 calls placed by their constituents, they found that most were for mental health services, health, and EMT and fire services, and not violent crimes. Part of the reason the police are called so often regarding matters of mental health is that programs that traditionally addressed those issues were cut in favor of increasing law enforcement budgets. “By dismantling the mental illness treatment system, we have turned mental health crisis from a medical issue into a police matter,” says John Snook, the executive director and co-author of a study by the Treatment Advocacy Center that found that people with untreated mental illnesses were 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter than other civilians approached or stopped by law enforcement.

A study by the Federal Reserve and cited by The Washington Post also found no correlation nationally between spending and crime rates. Over the last 60 years, the crime rate has risen and fallen as spending has spiked from a law enforcement budget of $2 billion in 1960 to $137 billion by 2018.

In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti is currently facing increased scrutiny from his constituents after the LA chapter of Black Lives Matter called to attention his proposed city budget that would allocate 54% of funds to the LAPD, something that the people of Los Angeles don’t want to begin with, according to BLM-LA Co-founder Melina Abdullah.

“When we engaged in a participatory budgeting session with Angelenos, they wanted to spend 5.7 percent of the city budget on traditional approaches to law enforcement. That includes LAPD, traffic enforcement, and the city attorney’s office — which is the prosecutor of the city.” Abdullah says. “People don’t want to spend this kind of money on police. When we look at those survey results, people saw this kind of approach to law enforcement as the least important of their spending priorities. Saying defunding the police moves us toward what most people say they want anyway.”

If we don’t have police, who will keep us safe?

This is an interesting question you’ll often see posed by those who are critical of the call to defund the police. It’s fair to wonder this, but it would also be wise to take into account the fact that as black and brown people in America we often don’t feel safe to begin with. Meanwhile, as more Americans take to the streets to protest unchecked police violence, it’s become clear that the “serve and protect” mandate has been interpreted by officers as running people over, beating them with batons, pepper-spraying them, and killing them.

If you’ve never had to deal with police violence or feared for your life during a routine traffic stop, then the idea of defunding or even abolishing the police may seem scary, but what defunding allows us to do is rethink how we keep communities safe. In a recent episode of Last Week Tonight, John Oliver broke it down simply, “Defunding the police absolutely does not mean that we eliminate all cops and just succumb to the purge. Instead, it’s about moving away from a narrow conception of public safety that relies on policing and punishment, and investing in a community’s actual safety net, things like stable housing, mental health services, and community organizations.”

Why do people think defunding the police is a better solution than reforming the system?

In truth, we can/should be working to reform the system even if we’re also taking action to defund the police. Community driven calls to action like Campaign Zero’s #8Can’tWait campaign, which seeks to urge law enforcement agencies to adopt eight use of force reforms that can immediately reduce killings, are great solutions that your local law enforcement agencies can implement immediately. No elections needed.

https://twitter.com/samswey/status/1268318672319401989

Campaign Zero has found that the police departments that have adopted their “use of force” policies kill significantly fewer people, and the departments that regularly exhaust all eight of their solutions before shooting see a reduction of 25% fewer killings by police. This is huge, but also begs the question: Is that the best we can do?

Speaking to WBUR, Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors says that only radical shifts can stop law enforcement violence. “It’s not possible for the entity of law enforcement to be a compassionate, caring governmental agency in black communities. That’s not the training, that’s not the institution. We have spent the last seven years asking for training, asking for body cameras. The body cameras have done nothing more than show us what’s happened over and over again. The training has done nothing but show us that law enforcement and the culture of law enforcement is incapable of changing.”

How can I find out more about this topic?

As you might have gathered by now, the subject of defunding the police is massive. You could write a whole book about it — in fact, someone has and you can download a PDF version for free right now. The End of Policing, by Professor of Sociology and Coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College, Alex S. Vitale, uses academic research to show the tainted origins of modern policing, and how the expansion of police authority is inconsistent with community empowerment, social justice, and public safety. You can also learn by following leaders who advocate for defunding the police like Melina Abdullah or Alicia Garza, as well as organizations like the ACLU, and Black Lives Matter.

Are we going to keep tinkering with the same old same old — or will we find the courage to transform? Imagine if WE believed we were worth more than short-term solutions. In 2014 we got body cameras. In 2020, we can have mental health serives, support for survivors…

— Alicia Garza (@aliciagarza) June 4, 2020

Money for schools, jobs that employ our people in addressing the problems in our communities. Treatment services. Move the money. Move the money. Move the money. Invest in community security. Community resources. Community power. #AAPF #UnderTheBlacklight

— Alicia Garza (@aliciagarza) June 4, 2020

While the issue is certainly new to many people, it’s not nearly as radical as it seems. It’s backed by data and sure to be a continual lightning rod in conversations about race and law enforcement in this country evolve.

“Defund” means that Black & Brown communities are asking for the same budget priorities that White communities have already created for themselves: schooling > police,etc.

People asked in other ways, but were always told “No, how do you pay for it?”

So they found the line item.

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) June 9, 2020